In the upper left corner of The Beatles’ Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band cover is a photo of Aubrey Beardsley, half-hidden behind the band’s first bassist Stuart Sutcliffe (whose untimely death had also occurred in his early 20s) and appropriately very close to Aleister Crowley, another Victorian icon often revisited by the Sixties’ counterculture.

Beardsley’s appearance on one of the most iconic record covers of the 1960s is more than justified. After all, and as Pat Gilbert explains on his piece Let’s Party Like It’s 1899 for Mojo magazine’s 2012 Magical Mystery Tour special, ‘it was the Aubrey Beardsley exhibition at the V&A in May 1966 that really got London’s Victorian/fin-de-siècle vibe going’.[1] An excitement brought about by selective memory and nostalgia for a decadent past soon made for an infatuation with Victorian aesthetics that was duly reflected in all things Pop culture, including clothing: London’s famous boutique I Was Lord Kitchener’s Valet became famous for its vintage military uniforms, popularised by the likes of Jimi Hendrix, Eric Clapton, and the Beatles themselves.[2]

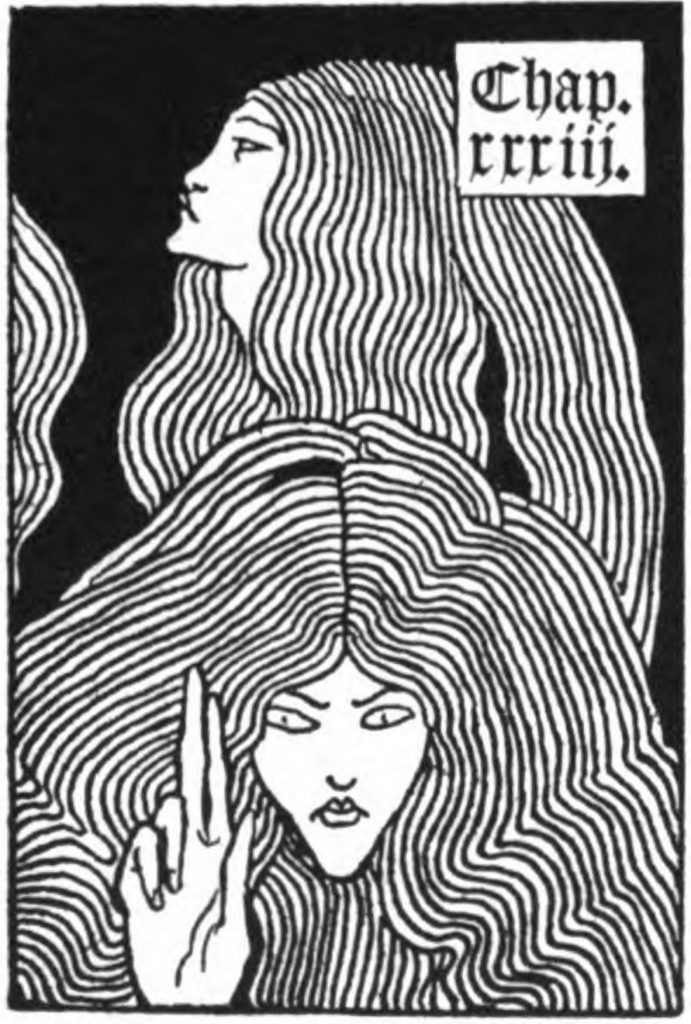

Beardsley’s influence on the birth of British psychedelia was so pivotal (Klaus Voormann’s drawings for the Beatles’ Revolver cover come to mind) that several details of his work were thoroughly used in posters and flyers, often colourised to appeal to a new generation – an example being the famous chapter heading from Le Morte Darthur.[3] In fact, influences from the period were so strong that the early days of psychedelia often felt like Victoriana on acid – an excess and escape Aubrey Beardsley would almost certainly approve of, since it spoke to the grotesque but also to a growing curiosity with all things occult and supernatural.

As a Pop Culture scholar with an ongoing PhD dissertation on issues of public image, representation, and identity in the Beatles’ films and videos (and an exceptionally big middle chapter entirely consecrated to their psychedelic era), I was thrilled to finally have a chance to witness first-hand a bit of the euphoria that the V&A exhibition had caused in the Swinging Sixties. A keen interest in both line drawing and the esotericism revival of the Victorian era made me fall in love with Beardsley’s work while I was still a teenager; and since my trip to London had been made impossible by the current circumstances, I was ecstatic to learn he was coming to Paris for a visit – just like he did in 1892.

The Musée d’Orsay seemed like the obvious choice to host Aubrey Beardsley’s first solo exhibition in France, since its main focus is on European art from the mid-1800s to the first decades of the twentieth century. Divided into three separate rooms on the second floor, the general display relied on colourful walls not only to distinguish the different sections but also to make the (mostly) black-and-white illustrations come to the forefront in contrast.

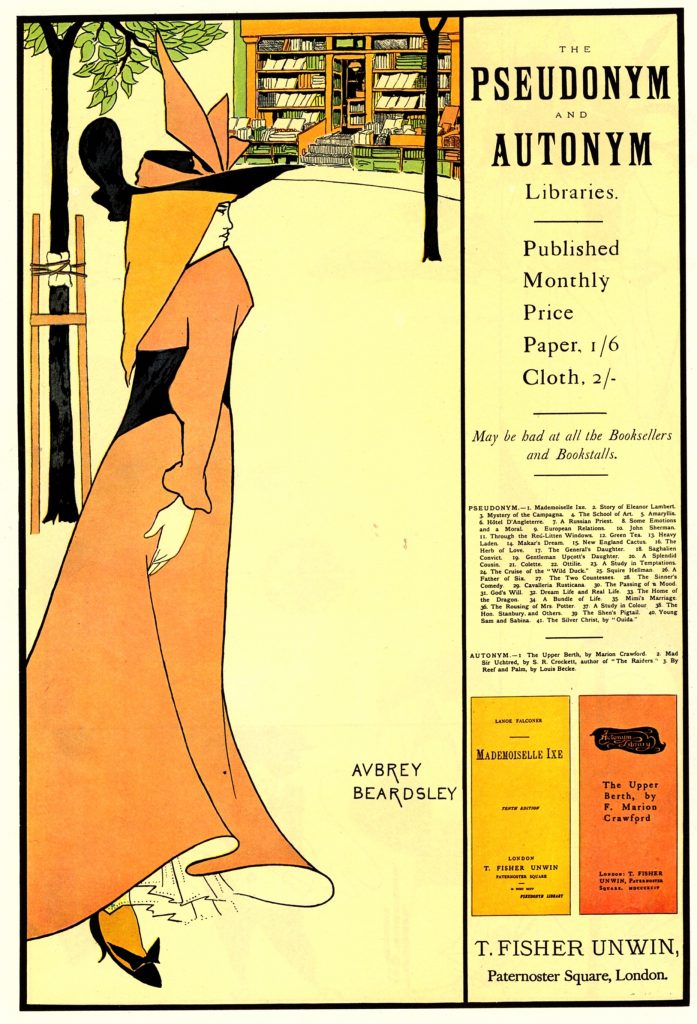

Unsurprisingly very focused on the influences Beardsley acquired during his many trips to Paris, the first room opens to a series of portraits and self-portraits in an effort towards a biographical contextualisation. The Pre-Raphaelite traits of his early works are thus juxtaposed to posters reminiscent of post-impressionist Toulouse-Lautrec, subsequently flowing into Le Morte Darthur and ending with a brief explanation of the impact Japanese illustration had in his art.

The second room is entirely dedicated to Salome, with the purple walls and low lights enhancing what are probably some of Beardsley’s most well-known illustrations, and where he seems to have arrived at his definitive style. It is, perhaps, interesting to note that one of the many adaptations of Oscar Wilde’s famous play was Carmelo Bene’s experimental 1972 film, which makes for yet another link (however indirect) between Beardsley’s universe and the Sixties’ counterculture.

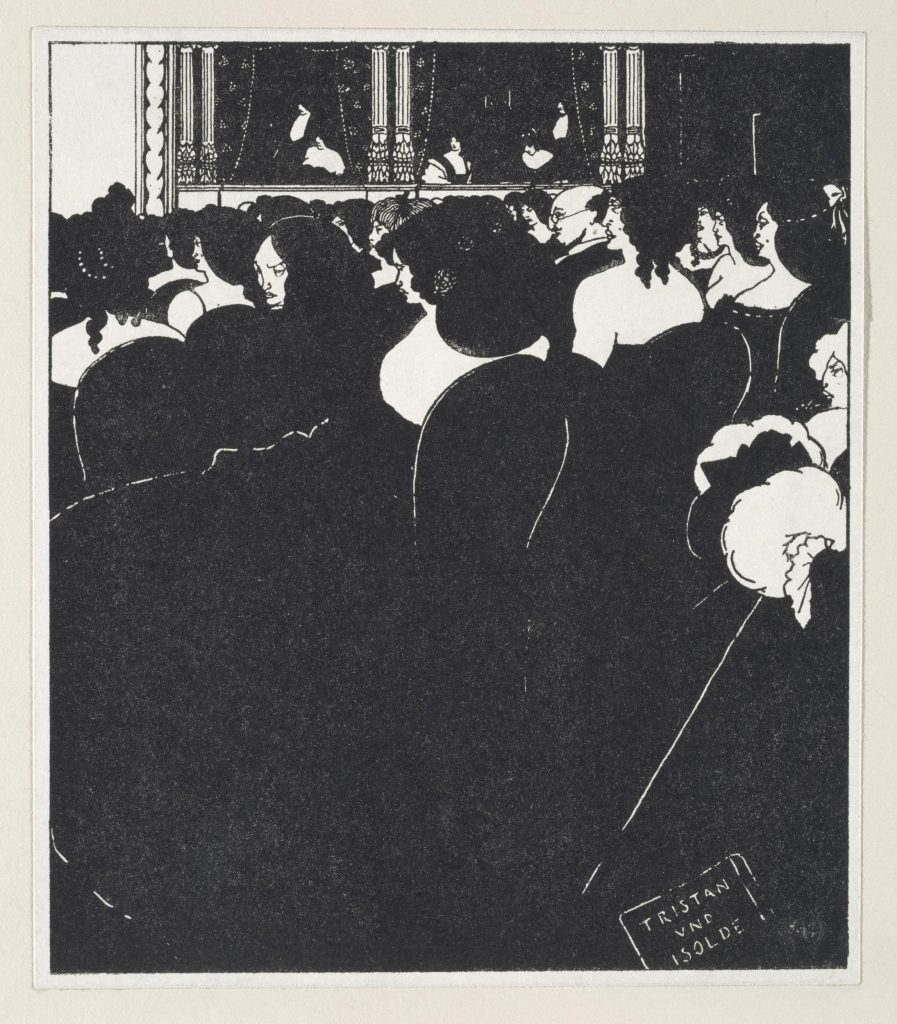

The third room begins with his Yellow Book era, which appears represented both through illustrations and actual copies of the magazine. A taste for the uncanny and the hors-norme is reflected by details such as Beardsley representing the public in The Wagnerites (1894) instead of the actual show; this seems to acknowledge an era where a fascination with backstage and other oblique perspectives became a standard, as seen, for example, in Degas’ portrayals of ballet recitals.

Alexander Pope’s The Rape of the Lock follows, highlighting a middle period which together with the Salome illustrations is quite possibly Beardsley’s work that influenced psychedelia the most; The Cave of Spleen (1896) in particular is a tourbillon of curves and details later found in psychedelic concert posters.

An appropriately red-walled corridor filled with his erotic Aristophanes and Juvenal illustrations leads to the last section, which sees Beardsley’s work for art magazine The Savoy siding with his last drawings. A couple of letter miniatures showcase an interesting mix between an obvious Arts & Crafts integration and medieval illustration, the latter also a major cornerstone for Art Nouveau and psychedelia.

When exiting the final room, the immediate sections of the museum are those dedicated to Art Nouveau and Symbolism, a happy coincidence (Orsay’s temporary exhibition rooms are fixed) that rings as a nice flow for someone coming from a heavy, dizzying dose of Beardsley. Short but intense, the exhibition unintentionally yet adequately ends up mimicking Aubrey Beardsley’s own life; two more years and he would’ve joined the 27 Club like a proper rock star.

[1] Pat Gilbert, ‘Let’s Party Like It’s 1899’, Mojo, October 2012, p. 75.

[2] Dominic Sandbrook confirms nostalgia for Victoriana was one of the most powerful influences in post-war culture, eventually reflecting on the bucolic branch of British psychedelia, which is usually referred to as ‘English Pastoral’; see White Heat: A History of Britain in the Swinging Sixties (London: Little Brown Book, 2006), p. 447.

[3] Juliana Duque argues that even ‘his choices of medium and method of reproduction for his illustrations bring Beardsley’s work towards psychedelia. Beardsley used the poster format to convey his artworks and favored low-cost printing’; see ‘Spaces in Time: The Influence of Aubrey Beardsley on Psychedelic Graphic Design’, H-ART. Revista de historia, teoría y crítica de arte, 5 (2019), p. 15-38. https://doi.org/10.25025/hart05.2019.02