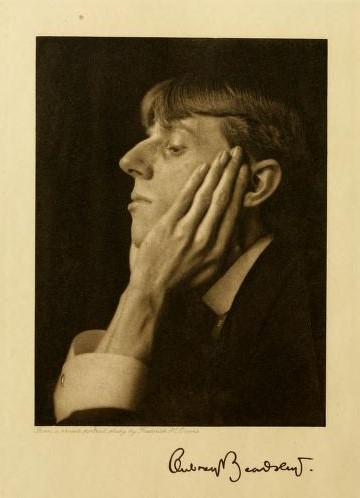

Strange though it may sound, the fact that Amsterdam’s Allard Pierson has a gorgeous art-nouveau exhibition waiting to open is owed in part to Beardsley. Beardsley is getting much international attention following the lavish overview exhibition Tate Britain dedicated to him last spring – the first in decades. The exhibition then went to the Musée d’Orsay. The catalogue characterises the gifted draughtsman as follows (p. 6):

Above all, Beardsley appears as an outsider because he was and still is one of a kind. Irreverent, grotesque, erotic and playful, Beardsley’s works drew freely from all sources, be that Ancient Greek vases, prints by Andrea Mantegna and Albrecht Dürer, French rococo paintings, Japanese woodcuts, or contemporaneous works by the Pre-Raphaelites, James Abbott McNeill Whistler, or Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. And yet his drawings were never derivative, displaying unbounded imagination.

During his short life, Beardsley was famous (as well as notorious) for creating often erotic drawings of a kind never seen before. Yet his fame faded at the beginning of the twentieth century. He kept being mentioned in art historical overviews, but became a bit ‘cultish’ nonetheless, which was mostly due to his association with ‘decadent’ fin-de-siècle culture. And perhaps the graphic and literary nature of his work, which includes many illustrations, made it hard to categorise exactly.

In the summer of 1966, the V&A held a large overview exhibition of Beardsley’s work, which became one of the main factors in the Jugendstil revival of the 1960s and 70s. Numerous ‘psychedelic’ music posters and lp covers bear witness to it. The Beatles’ Revolver (1966) is a good example; its designer, Klaus Voormann, was inspired by a visit to the Beardsley exhibition.

The ‘decadent’ and mystical elements, the exotic designs and the interest in drugs, mysticism and counterculture displayed by the modern arts around 1900 were a perfect fit with the counterculture of the 1960s and 70s. In the Netherlands as well, every household with even the slightest claim to hipness owned a Toorop, Beardsley, Klimt or Mucha picture or reproduction.

Art historians in the Netherlands were relatively late in developing an interest in Art Nouveau and Symbolism, which may have been partly due to the fact that in Dutch fin-de-siècle art these movements, tendencies, developments – whatever one wants to call them – were not as clearly present as in, for instance, France or Germany. The fact that Art Nouveau with its emphasis on ornament and decoration and Symbolism with its fascination for the fantastic and the decadent did not suit the allegedly down-to-earth Dutch all that well may also have been a factor.

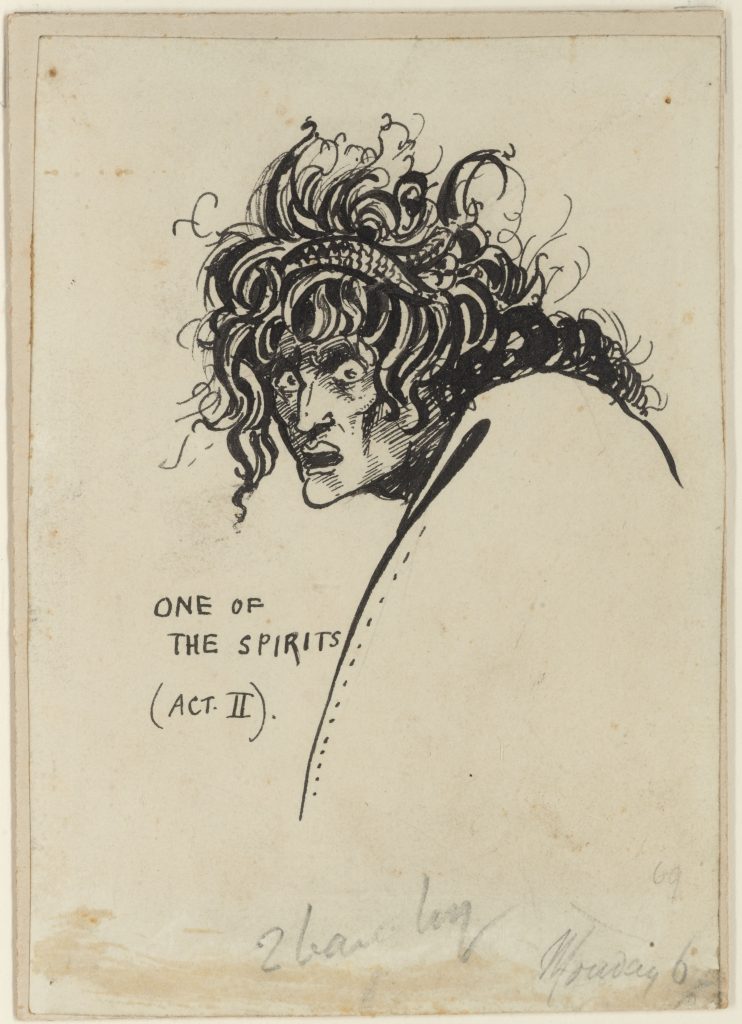

One of the Spirits

The Allard Pierson is lucky to have an original Beardsley drawing in its collections – as far as we know, it is unique in the Netherlands. We owe the drawing to a Theatre Institute curator who in 1975 had his wits about him at an auction and bought it for 672 guilders, the equivalent of 900 euros now: a real bargain. The auction catalogue described the powerful ink drawing of 14.5 × 10 cm as ‘Salomé – portrait of an actress in the second scene of One of the Spirits’. It disappeared into a storeroom at the Theatre Institute, whose collection later became part of the University of Amsterdam Special Collections, and was rediscovered last year during preparations for Goddesses of Art Nouveau, an exhibition that owes many objects to the treasury that is Special Collections. The portrait had not been completely forgotten – it had been catalogued – but it is now presented to the public for the first time.

‘A New Illustrator: Aubrey Beardsley’

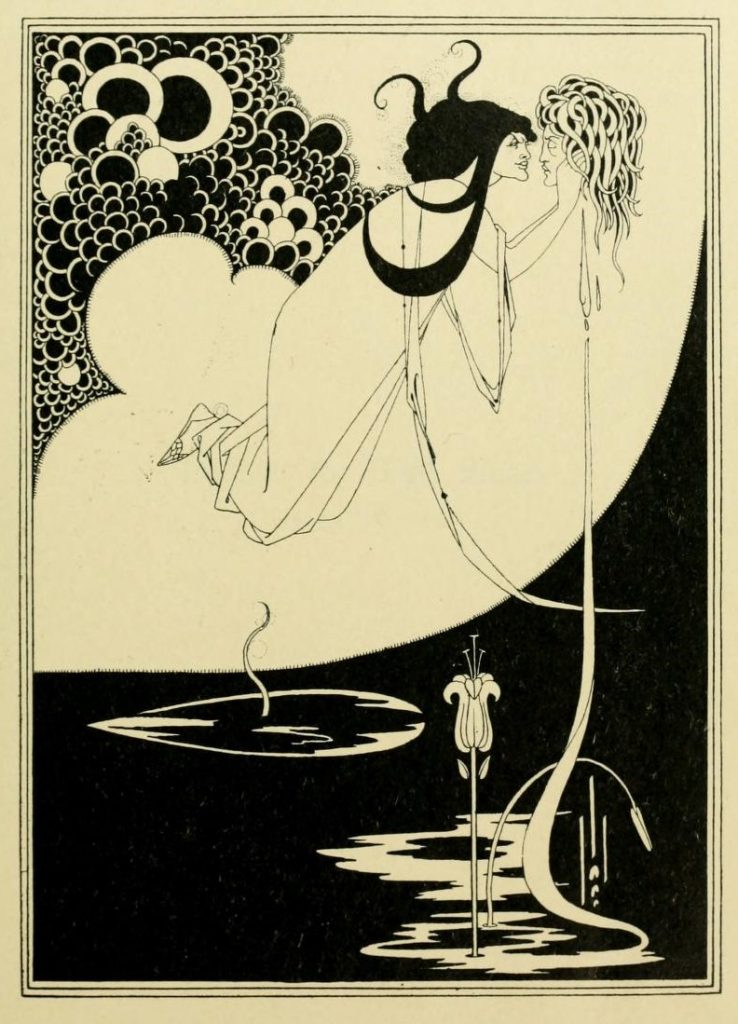

In July 1891 Edward Burne-Jones gave Beardsley some sound advice: ‘Give up whatever you may be doing – for Art’. Until that point, the nineteen-year-old civil servant had only been drawing to entertain himself, but he took the advice to heart immediately. In 1892 the drawings and book illustrations that brought him fame started appearing. In that year he illustrated the majestic edition of La Morte d’Arthur; April 1893 saw the first issue of the art magazine The Studio, with a lavishly illustrated contribution titled ‘A New Illustrator: Aubrey Beardsley’, which successfully introduced the British public to Beardsley. In the same year, he made the illustrations for Wilde’s Salome which soon became classic, and in 1894 the first issues of the famous magazine The Yellow Book appeared. It was thanks to Beardsley’s covers that ‘London suddenly turned yellow’.

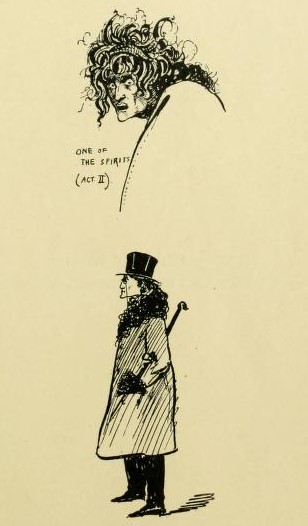

The drawing in the Allard Pierson’s collection dates from the very beginning of Beardsley’s career. In February and March 1893, before his breakthrough with the Studio piece, Beardsley made some twenty-five drawings and sketches for The Pall Mall Budget magazine. They were caricaturish illustrations for contributions on art, literature, theatre and music. Drawing for this magazine was ‘Beardsley’s first chance to reach an audience beyond the art coteries, and his head was beginning to dizzy from the sudden eruption of praise and opportunity’ (S. Weintraub, Beardsley: A Biography, 1967, p. 46). The Amsterdam drawing was published on 16 March 1893, one of four illustrations of an article on a performance of C. W. Gluck’s opera Orfeo ed Euridice (1762), translated as Orpheus, at the Lyceum Theatre. A press proof is kept in Princeton University Library.

It was not just his prolific imagination that guided the draughtsman’s hand: Beardsley actually went to a performance and possibly made the drawings on the spot, as is certainly suggested by a little sketch he made of a member of the audience. In Act II the mythical singer Orpheus encounters the Erinyes, Greek goddesses of vengeance who are called ‘spirits’ here. They refuse to let him pass after bringing back his beloved Eurydice from the underworld but yield to his enchanting song in the end. Beardsley depicts the goddess as an intimidating Medusa, expressly placing her in the nineteenth-century ‘tradition’ of ‘dark romanticism’. Mario Praz in his classic work The Romantic Agony (1933) considers Medusa the example par excellence of the ‘new sense of beauty, a beauty imperilled and contaminated, a new thrill’. Praz quotes Walter Pater, the British theoretician of aestheticism and decadence, who wrote about Medusa: ‘What may be called the fascination of corruption penetrates in every touch its exquisitely finished beauty’.

The title Salome in the auction catalogue is not entirely correct: Salome does not have Medusa hair, for instance. As Praz explains at length, the representation of ‘woman as Medusa’ in the course of the nineteenth century is gradually replaced by the image of ‘woman as Salome’: a development that could be linked to an increasingly ‘problematised’ and mostly sexualised image of women, because Salome, more than Medusa, is driven by lust. To many modern writers and visual artists, female lust was very threatening. Various contributions in the book accompanying Goddesses of Art Nouveau deal with this aspect.

The drawing titled The Climax, which Beardsley made for Wilde’s Salome in 1893, probably is one of the most striking and rightly famous depictions of a femme fatale ever made—so the title in the auction catalogue is not entirely unfounded. In the first overview publication, The Early Work of Aubrey Beardsley (1899), the drawing was printed as plate 56, titled Sketch from Orpheus at the Lyceum. The reproduction must have been made from The Pall Mall Budget: a comparison to the original shows that some lines at the edges of the hair have partly disappeared.

The route to the Netherlands

We don’t know whether the original drawing was kept by its maker or stayed in the magazine’s archives, nor how it ended up in the Netherlands. There are some links between the Yellow Nineties and the Netherlands, so perhaps the painting crossed the Channel then (see S. Bink, ‘Beardsley en zijn Nederlandse navolgers’ [‘Beardsley and his Dutch followers’], Jaarboek Rythmus, 2012)—but it seems to have left no trail to the auction in 1975. The Orpheus illustrations are mentioned in Robert Ross’s early standard work on Beardsley (1909). At the V&A exhibition of 1966 ten drawings for The Pall Mall Budget were shown, but none of the Orpheus drawings; the ones on display were all from the V&A collection and a few private collections.

The private collector who owned One of the Spirits at the time apparently did not contact Beardsley scholar Brian Reade, whose main aim with his book Aubrey Beardsley (1967) was ‘to reproduce as many drawings as possible by him as became available after the exhibition of 1966’ (p. 24). Perhaps the drawing was already in a Dutch collection then, to which Reade did not have access. Although Beardsley’s exotic and erotic work was doomed to a mere cult following in the ever-decent Netherlands, he did in fact generate an interest among the more progressive artists, actors and writers (see Bink 2012).

Regardless of where this uniquely powerful drawing has wandered, we will soon be able to admire it in Amsterdam, together with spectacular works by his greatest contemporaries.

With special thanks to Caroline Corbeau-Parsons, Tate Britain. Translated by Corinna Vermeulen.