I must start this review with a disclaimer regarding my academic background, which may explain the approach that I take to Aubrey Beardsley’s oeuvre and the recently re-opened Tate Britain exhibition. I am an art historian, but I specialize in medical and surgical art, with a particular personal interest in anything considered ‘morbid’. Therefore, when entering the Tate, I found myself drawn to the elements of this show that dealt with illness and all themes and images that were grotesque, taboo, and decaying. Perhaps this focus also had something to do with the fact that this was my first visit to a museum since lockdown had lifted and, as with many of us, illness has been at the forefront of my mind for several months.

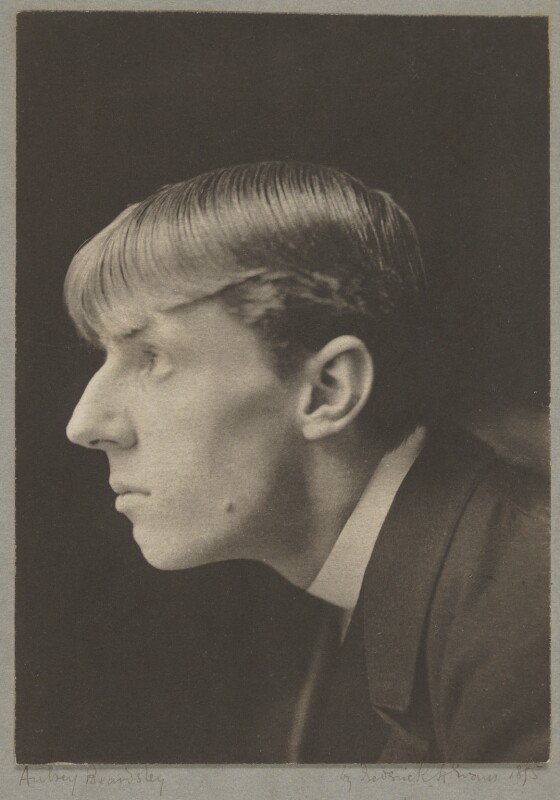

As someone working within the medical humanities, before visiting this show I was most familiar with stories and images of Beardsley’s gaunt, lithe, tuberculosis-stricken body, and with the mythologising of his illness and untimely death at age twenty-five. His death is often romanticised, as his story suits the dramatic tragedy of a typical male ‘great artist’ narrative. But, as befits the reputation and image of someone as revered today within the queer community as Aubrey Beardsley, depictions and descriptions of his disease, tuberculosis, were entwined with feminine beauty, frustrated passion, and drooping passivity in the late Victorian period; this is a conceptualisation of the disease that I first came across in Susan Sontag’s Illness as Metaphor.[1] Beardsley was diagnosed with tuberculosis at age seven, but, as was often the case, the symptoms only erupted years later to become the haemorrhages that eventually killed him.

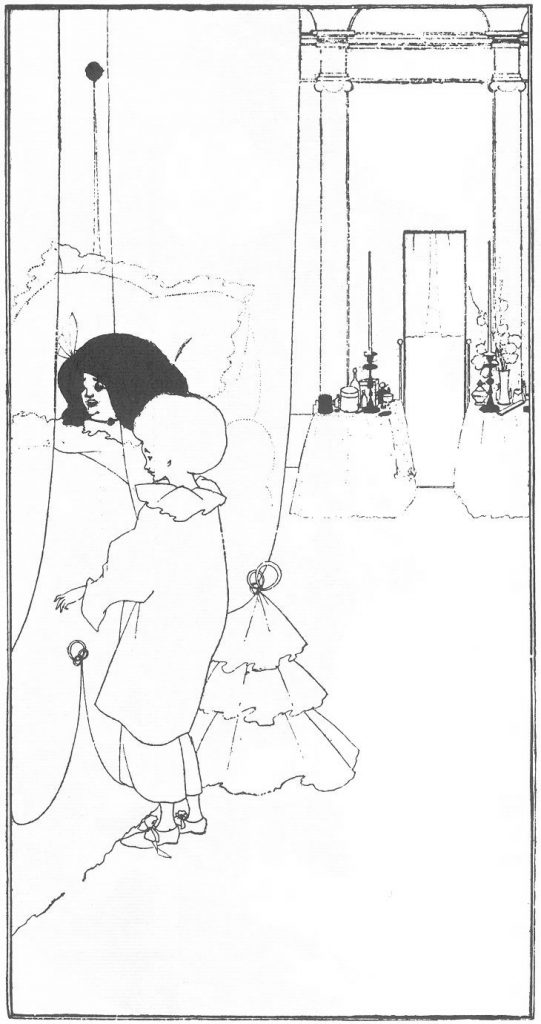

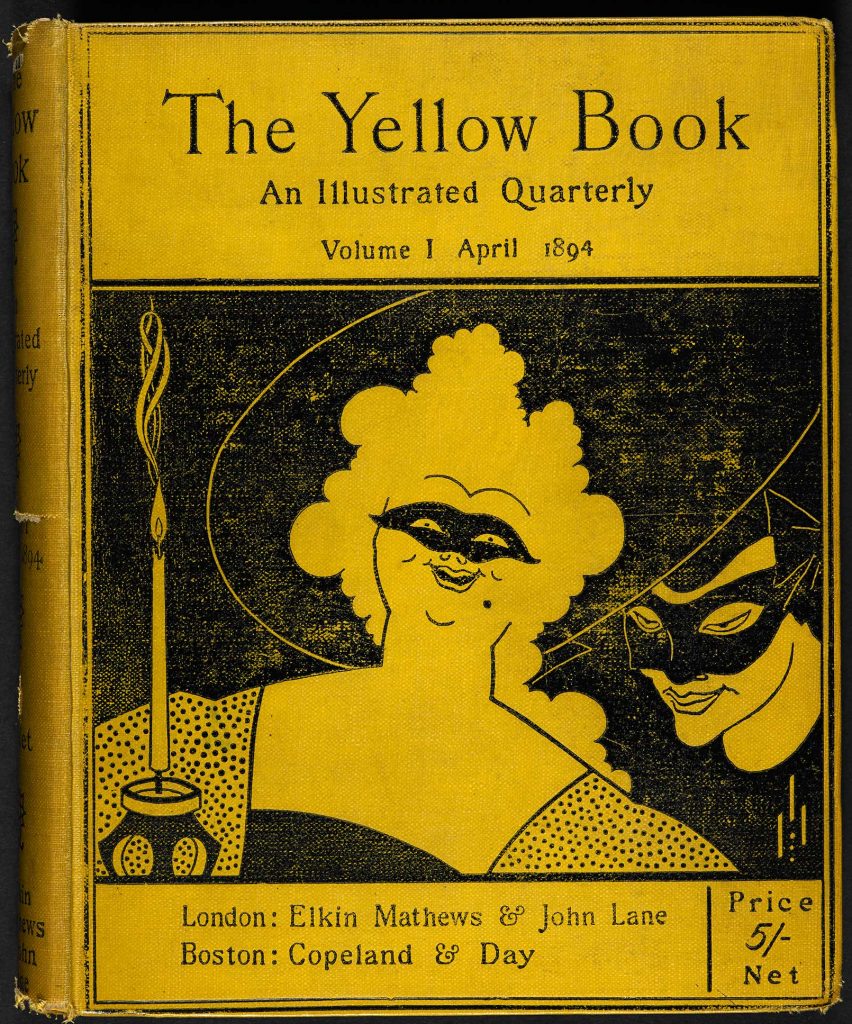

Like this languishing, latent, lustful Victorian perception of tuberculosis, this exhibition is a slow, but beautiful, burn – one that is expressed in fits and starts. Beautiful, because of the undeniable quality of Beardsley’s line and compositional eye; slow, because there were points at which it felt like this show paused and diverted away from the truly explosive narrative of Beardsley’s unusual and often grotesque artistic power. Sontag describes tuberculosis as ‘a disease of extreme contrasts,’ in which the patient ‘is wracked by coughs, then sinks back, recovers breath, breathes normally; then coughs again.’[2] My response to Beardsley’s drawings in this show felt delayed at several instances, like tubercular symptoms. The most glaring point at which the excitement goes latent is in a central room of the show that displayed photographs and artistic representations of and by Beardsley’s circle. The walls of this space were painted orange – a colour that the curators may have hoped (in vain) could subconsciously drum up a thrill similar to that of the lurid and erotic yellow of the literary periodical that Beardsley illustrated, The Yellow Book. This room concentrated on Beardsley’s friends and family, taking the viewer out of the fantastical narrative of grotesque decadence that was being built up in previous rooms. These paintings and drawings paled in comparison to Beardsley’s own production.

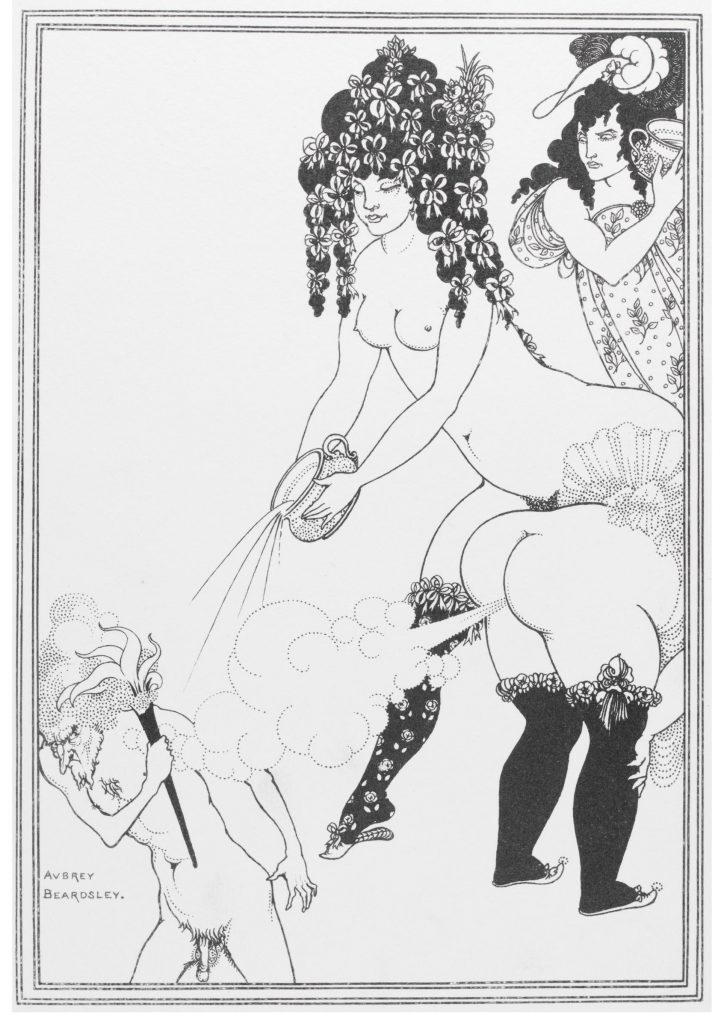

In contrast, the symptoms of decadence and perversion erupt most violently and satisfyingly in an eggplant-coloured alcove (perhaps a nod to that most suggestive of emojis?!) within the show’s large final room. These three purple walls are introduced with a content warning: this space holds Beardsley’s Lysistrata drawings, the most overtly sexual of his oeuvre, although sexualised details and explicit phalluses appear several times in earlier rooms in this show. The placement of this alcove fits with my loose concept of this show as tubercular, as it is just before the end that the ugly (but beautiful, as tuberculosis is historically depicted) head of disease finally rears the full extent of its nastiness. In this context, however, the nastiness is what we, as viewers, have longed for all along.

Returning to the colours that dominated this show, and their connections to illness, there was a subtle yellow theme throughout the exhibition. The yellow walls in the show’s second room ostensibly hint at the forthcoming exploration of The Yellow Book, perhaps Beardsley’s most famous contribution to British visual culture. But in addition to this, the association of points to a further connotation of the colour yellow: it can be likened to the particular hue of coughed-up sputum that suggests a lung infection diagnosis. The colour of the walls also reminds viewers of another late Victorian artistic rumination on illness and confinement: Charlotte Perkin Gilman’s The Yellow Wallpaper.

The last room of this exhibition suggests that the ‘sickness’ that Beardsley began during his lifetime has continued to spread and to infect millions of people around the world. One of my favourite works from this final space, In Memoriam (c. 1923) by an unknown artist, imagines a death-bed scene, compiled of Beardsley’s own characters – both the fashionable and the grotesque. The time-tested fixation on the taboo elements of his work, as well as his distinctive forms and lines, shows that the Beardsley disease is here to stay, with no vaccine en route, or, for that matter, desired.

[1] Sontag points to paintings by the artists of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and by Edvard Munch as representational images of this visual idea of tuberculosis. Susan Sontag, Illness as Metaphor (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1977), 25.

[2] Sontag, Illness as Metaphor, 11-12.