Aubrey Beardsley arrived at Menton on the French Riviera on the 20th November 1897. He was suffering from the advanced stages of tuberculosis of the lungs. He had been a chronic invalid for the past eighteen months, but still held hopes that the mild climate of the South of France might soothe his condition.

In the late 19th century little was known about the true cause of his disease (the tuberculosis bacterium) or the best means of its treatment. Fresh air and a balanced, preferably sunny, climate were thought to be the best cure. In search of these conditions Beardsley (for the most part accompanied by his mother) had passed the previous year-and-a-half in a slow pilgrimage from health resort to health resort: Crowborough, Epsom, Boscam, Bournemouth. From these South Coast havens, he had moved on to France, staying at Paris, St Germain-en-Laye and Dieppe, before – in November 1897 – finally travelling down to Menton, on the French Riviera.

Menton, a town much swapped between Genoa, Monaco and France (and hence often called Mentone), provided, it was thought, ideal conditions for the consumptive. Its fame had been established by a consumptive British doctor, Henry Bennet, who had come to the town in 1859 ‘in order to die in a quiet corner’ and, to his own astonishment, had got cured instead. Dr Bennet’s book, Winter in the South of Europe: or Mentone and the Riviera as winter climates (1861, and reprinted many times since), encouraged a yearly stream of British invalids to descend upon the town, in some cases with positive results.

Nor was Menton’s mild climate (said to be the warmest on the Riviera) the only attractive attraction for these visitors. After Queen Victoria spent a couple of weeks in Chalet Rosier on the Boulevard Garavan in 1882 the town became absolutely de rigueur with the British aristocracy. They would flock there in the winter in order to enjoy the ‘Riviera season’. (The taste for sunbathing and the summer sun is a very recent innovation; in the nineteenth century most of Menton’s hotels were open only between October and May).

As a result of these fashionable and medical endorsements, Menton also provided services for British visitors. In 1898, there were five English doctors residing in the town, including the Beardsleys’ choice – Dr Campbell; there was a British pharmacy proudly calling itself ‘chemist to Queen Victoria’; there was a British laundry (‘washing done by hand’); there was an English bakery and an English butcher (‘selling only the purest juices of the finest English meat’) – clearly, French cuisine was not yet to be trusted. There were several English language newspapers that faithfully published the names of all foreign visitors and their whereabouts.

Aubrey Beardsley and his mother took rooms at the Hôtel Cosmopolitain. It was a popular destination. The local papers indicate that at the time of the Beardsleys’ arrival there were about thirty other British people staying at the same hotel.[1]

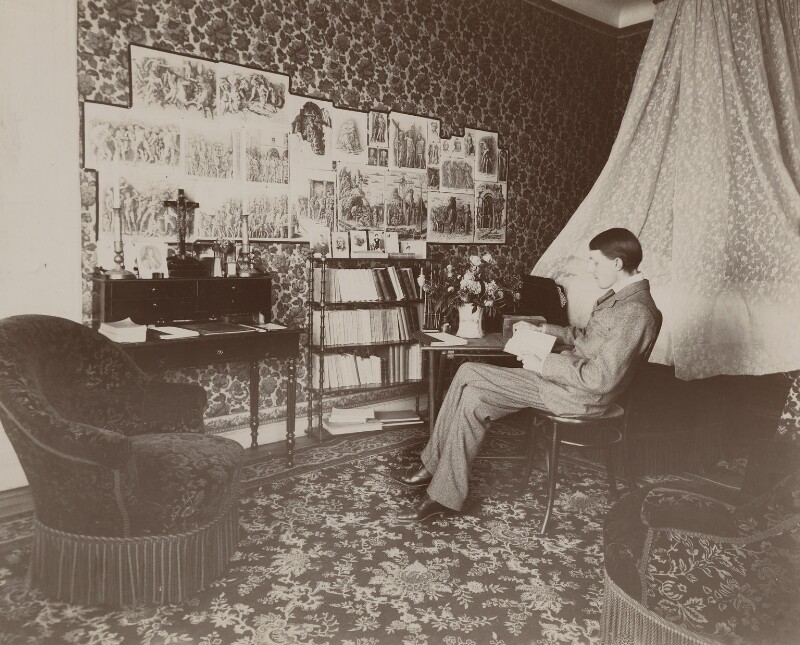

The train journey from Paris, which took in those days a full twenty-four hours, had totally exhausted the artist, and during his first days in the new town he did nothing but rest. He was, however delighted to find himself ‘charmingly installed in a good hotel in its own grounds.’ ‘My room’, he announced, ‘is quite palatial with the sun all the live-long day.’[2]

Beardsley described the hotel as being slightly out of town and on top of a hill, surrounded by a private garden. The 1894 Baedeker provides practical details. The Hôtel Cosmopolitain is listed as ‘a large detached house’ and rewarded with an asterisk. Rooms cost 2 to 5 francs, a candle was 50 centimes and full pension 8 to 14 francs.[3] It was not cheap, but Beardsley, with the quarterly allowance of £100 pounds he was receiving from André Raffalovich, together with the occasional cheques from Smithers, could certainly afford it.

No Hôtel Cosmopolitain is listed in the current Menton directory, and some detective work was necessary to discover its former location. The annually guides of the ‘Alpes-Maritimes’ first mentioned the Hôtel Cosmopolitain (director: Joseph Arthur Widmer) in 1890. It was located in the ‘quartier de Vignasses’, on the hill behind Menton’s station, between the river beds (now traffic arteries) of the Borrigo and the Carei. Its site was considered particularly beneficial due to its fusion of sea and mountain air.[4]

The ‘quartier de Vignasses’ is still a green quarter of the town, full of luxurious villas and sweet-smelling gardens. Three gigantic south-facing palaces, visible even from the sea, dominate the hill: Hôtel Montfleuri, an oblong building with a creamy facade and light-blue, cast-iron balconies; the sumptuous neo-baroque Riviera Palace with its challenging pink stucco front and the stark white Winter Palace with its two bell turrets borrowed from Garnier.

The detailed maps in the annuary guides of 1897 and 1898 suggest that the only developed area in the ‘quartier the Vignasses’ at that date was around the current site of the Hôtel Montfleuri. The Hôtel Cosmopolitain, moreover, disappears from the annuaries in 1899. In the following year the Hôtel Montfleuri (director: L. Navoni) is recorded for the first time; Mr Widmer, meanwhile, having become the proprietor of the recently completed Riviera Palace. The supposition that the Hôtel Montfleuri was indeed once the Hôtel Cosmopolitain was confirmed by an advertisement in the Menton and Monte Carlo News.[5]

The change-over obviously entailed some redecoration: an ornamental pedestal bearing the initials L.N. (L. Navoni) and the new name of the hotel was erected outside the south-facing facade. But the basic structure, it seems, remained the same: four stories built in a sober classical style, with a slightly projecting central portion on the southern side. All the south-facing rooms have their own balconies, and these, along with the woodwork, are painted a light blue. Only the first floor to the north still functions as a hotel; the rest of the building is private residences.

The terrain in front of the building slopes gently down the hill but the garden, where Beardsley used to sit under the trees, has largely disappeared. Most of the area in front of the house now consists of a parking lot. In the middle of it, however, there is a patch of garden with a number of stately palm trees which could date back to Beardsley’s day. The curly decoration of the cast-iron grille which surrounds the boundary wall has about it a suggestion of Beardsley’s work.

On the other side of the street, in the gardens of the Villa Ar-Mor, the subtropical landscape ascends the neighbouring hill in carefully cultivated terraces up towards the still privately owned Chateau Marni, onto which Beardsley must have looked from his hotel room. Grapefruits and mandarins dangle in the orchard, and around the distant red-brick castle solemn cypresses and pine trees rise towards the sky.

The south-east view is limited by the many houses and apartment buildings erected in this century, but over this approaching urbanism the hotel still offers an outlook upon the sea.

On a Sunday in March, it is still as silent as it must have been in Beardsley’s time. I recognise the songs of thrushes and a black cap; seagulls circle overhead, and the distant crack of a rifle shot can cause the pigeons to scatter in panic from the sloping roof of the hotel.

Beardsley’s stay at the Cosmopolitain was filled at first with work for an illustrated edition of Ben Johnson’s Volpone and then by the grim necessities of his rapidly declining condition. In January 1898, he was, however, still well enough to register the excitement of the early spring. He told Raffalovich: ‘You would be delighted with the flowering shrubs here; and trees like the mimosa literally sing with bees’. The excitement of the Menton Carnaval made less impression.

The tradition of the Carnaval still continues at Menton: it is now called the Lemon Festival. In the 1890s, it was a rather more mundane affair. From the beginning of the new year, the local newspapers excitedly announced the programme. In 1898, there were to be ‘two Battles of Flowers’ – contests of superbly decorated floats – with eight magnificent banners for the lucky winners. February the 16th would see the entry of King Carnaval, followed by several ‘Battles of Confetti’. The festivities would conclude in March with a Regatta, ‘terminating probably with the illumination of the East Bay of Garavan’, an impressive yearly spectacle which had been initiated at the time of Queen Victoria’s visit.

In mid-February, the Menton and Monte Carlo News was enthusing that ‘the season is now at its height, and that everywhere, from the largest hotel to the smallest inn, is now full… Amusements are provided for every hour, not a night passes without a ball and the days are given over to receptions, luncheons, dinners, drives and bicycling, besides the excitement of battles of flowers and confetti’.[6]

By then, however, Beardsley was confined to bed, unable to work or to take part in the festivities. It is a measure of his condition that he did not mention the carnival preparation in his letters, even though the Cosmopolitain sent a Russian troika to the first battle of flowers, decorated with mimosa and carrying eight maidens with distinctly English names. The second ‘battle’ included an ‘excessively pretty carriage’ containing a miss Widmer (the former proprietor’s daughter?) costumed and masked in white and surrounded by white marguerites’. The image would surely have delighted Beardsley had he been well.[7]

Beardsley’s tubercular ‘blood spitting’ had returned, though he pretended to his friends back in England that he was laid low merely with rheumatism. He was too weak to shave. The final crisis was near at hand. On the 7th of March, he wrote his famous letter of renunciation urging Smithers to destroy all his ‘obscene drawings’. Mabel arrived from London soon afterwards, and – together with their mother Ellen – was at his bedside when he died in the early hours of 16 March 1898.[8]

The following morning there was a Requiem mass in the Cathedral of Saint Michel in the centre of Menton. Afterwards, under a cloudless sky, Beardsley’s coffin was carried through the old town up to the cemetery on the hill above Menton. It was escorted by a small procession; almost all the guests still at the hotel took part.

‘I want you to know how beautiful everything was,’ Mabel wrote to Raffalovich. ‘There was music. The road from the Cathedral to the Cemetery was so wonderfully beautiful, winding up a hill; it seemed like the way of the Cross; it was long and steep and we walked. His grave is on the edge of the hill; it is hewn out of rock and it is a true sepulchre with an arched opening and a stone closing it. We thought of the sepulchre of the Lord…’

Every year since 16 March 1991, a small procession has mounted this Via Dolorosa from Menton cathedral to the Cemetery of Le Trabuquet. Our company consists of a Dutch painter, a former Anglican priest and his wife, and elegant, somewhat fragile Englishmen of the kind Beardsley himself might have become if he had been allowed to live; the British consul on the Riviera, some local intellectuals and myself. The sky is always a brilliant blue, and once we have left the narrow streets of the old town behind us we hear nothing but the sighs of the cypresses, swinging in the spring breeze. Once we have reached Beardsley’s grave, we can look out over the whole of Menton.

At twelve o’clock sharp church bells begin to ring in the town beneath. Birds circle overhead and below, the sea wrinkles soundlessly towards the far horizon. A cat, perhaps, disappears warily between two graves. Carefully, we deposit our lilies on the warm tombstone at our feet.

Endnotes

[1] Menton and Monte Carlo News, November 1897-March 1898

[2] Beardsley’s letters are quoted from Maas, Duncan and Goods (eds.), The Letters of Aubrey Beardsley, (London, 1970)

[3] Carl Baedeker, Le Sud-Est de la France, du Jura à la Méditerrannée, y compris la Corse, (Paris, 1894)

[4] Cazenave de la Roche, Climat de Menton et spécialisation médicale, (Nice, 1882), pp. 66-67

[5] Annuaires des Alpes-Maritimes, (Nice, 1889-1900); Menton and Monte Carlo News, 9 December 1899

[6] Menton and Monte Carlo News, 19 February 1898

[7] Menton and Monte Carlo News, 29 January and 19 February 1898

[8] Beardsley’s death certificate is reproduced in Brigid Brophy, Beardsley and his World, (London 1976), p. 111. It gives Beardsley’s age and the date of his death incorrectly