Author’s note

I originally became interested in Beardsley’s two drawings of the Roman empress Messalina and their precise iconography in the early 1980s. In 1983 I included them, together with some of the relevant lines from Beardsley’s source of inspiration for the drawings, the Latin poet Juvenal’s ‘Sixth Satire’, in my volume Beardsley, published by Phaidon that year. I had however noticed that throughout their history these two drawings had been confused and their respective subjects misunderstood. Although I had established their correct identity in my 1983 publication, in 2002, I read a paper to an informal internal curatorial research group at Tate Britain that set things out much more fully. What follows here is a modified version of that paper, which was never published.

Sources

Reflecting its informal origin, this essay is not footnoted. All the factual material given here relating to the two drawings has now been gathered together in the extensive accounts of them given by Linda Zatlin in Aubrey Beardsley A Catalogue Raisonne (2016), where she also cites my 2002 paper, which I had sent her. I have also integrated broad source references into the text.

I have not explored the question of the earlier translations of Juvenal that Beardsley referred to as part of making his own translation of the Sixth Satire, now sadly lost. He owned a copy of the 1697 version by Dryden, which is however very free, omitting crucial detail. Although Beardsley is known to have referred to several other translations, I have used a scholarly modern version, Juvenal, The Sixteen Satires, translated and with an Introduction and Notes by Peter Green, London 1974. That Beardsley himself arrived at a similarly accurate rendering is evidenced by the correspondence of the drawings themselves to Green’s text. The historical information on Messalina and her husband Claudius comes from accounts by the American historian Garrett Fagan found here.

Introduction

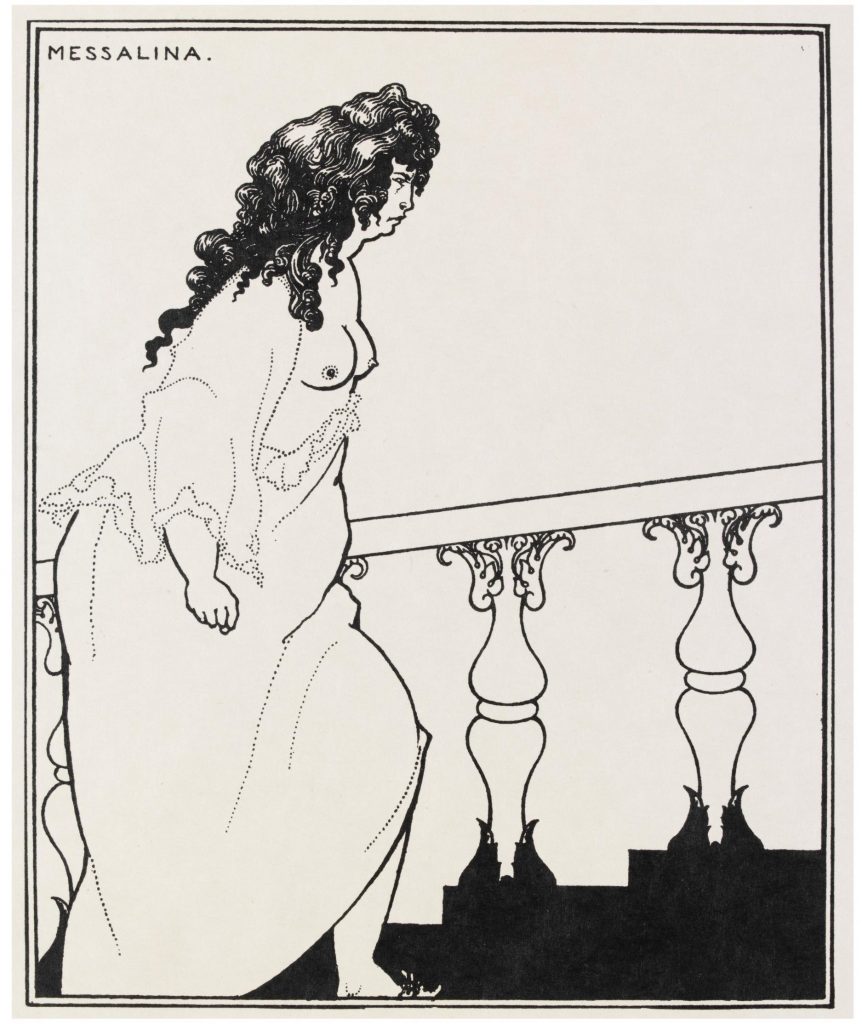

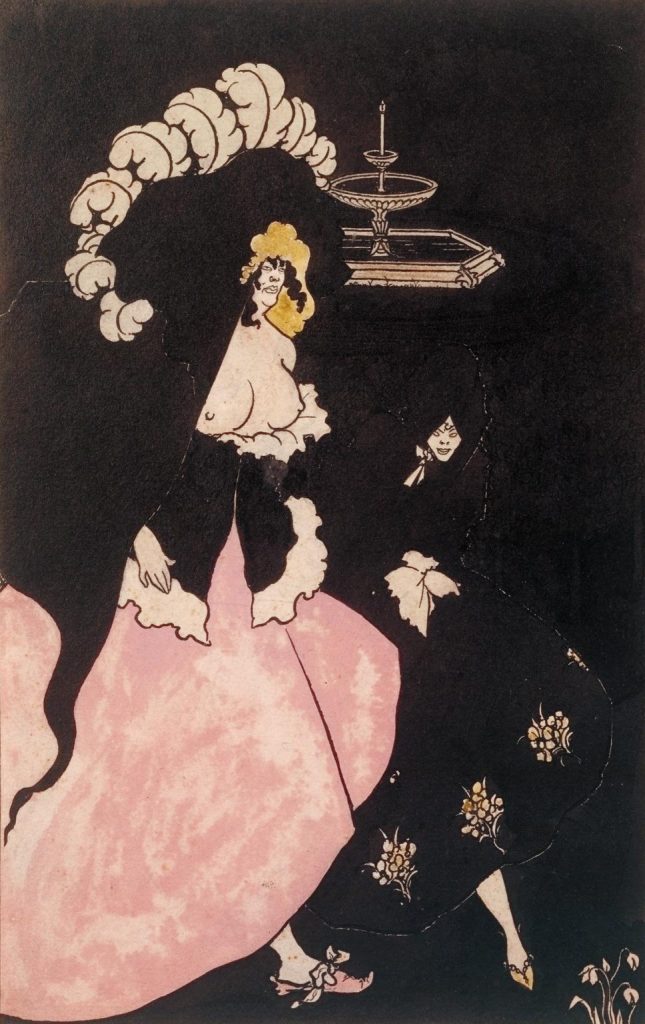

In the summer of 1896, Aubrey Beardsley embarked on an ambitious scheme to produce an illustrated edition of the Latin poet Juvenal’s Sixth Satire, to be newly translated from the original Latin by himself. In the end, he produced only four drawings, one of which was of the Roman empress, Messalina, to whom Juvenal devoted a notorious passage of the work. But Juvenal’s account of Messalina had clearly been on Beardsley’s mind for some time, since he had already made a drawing of her, which Zatlin dates to c. February 1895. Of these two images of Messalina, one is now in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum (Messalina Returning from the Bath 1896), the other is in the Tate Collection (Messalina and Her Companion 1895).

Juvenal

In the introduction to his translation of Juvenal (see Sources, above), Peter Green tells us that Juvenal was a Latin poet of whom almost nothing is certainly known. He is thought to have been born around 55AD and to have died sometime after the death of Emperor Hadrian in 138 AD. He is remembered for his sixteen satires on Roman society of the time and particularly for his Sixth Satire, known as the Satire on Women, a swingeing attack on the morals of upper-class Roman women and on the institution of marriage. Part of the background to this satire, Green also tells us, is the situation of women in Rome of this period, when they apparently had certain advantages. These partly arose from the practice of female infanticide, which resulted in a shortage of women, and partly from the peculiarities of Roman marriage law which in effect made multiple marriages easy for women. In other words, it looks as if Roman women were behaving a bit like men, and that being the case Juvenal, as a traditional male, would clearly have had a massive axe to grind.

Messalina

Valeria Messalina was the third wife of the Roman emperor, Claudius I. The story of Claudius is, of course, a deeply fascinating one – the sickly prince who by appearing a buffoon survived the murderous infighting of the court of the notoriously tyrannical Emperor Caligula. When Caligula was killed by his own bodyguard, the Praetorian guard declared Claudius the next emperor. To everyone’s surprise, he turned out to be rather good at it, although clearly, he had a fatal flaw in his judgement of women – literally fatal since his fourth wife poisoned him.

Claudius had married Messalina, a noblewoman and another member of Caligula’s court, in 38 AD, three years before he became Emperor. She was sixteen, and he was forty-eight. The American historian Garrett Fagan writes of her: ‘In the sources, Messalina is portrayed as little more than a pouting adolescent nymphomaniac who holds wild parties and arranges the deaths of former lovers or those who scorn her advances; and all this while her cuckolded husband blunders on in blissful ignorance. Recently, attempts have been made to rehabilitate Messalina as an astute player of court politics who used sex as a weapon, but in the end, we have little way of knowing the truth. What we can say is that either her love of parties (on the adolescent model) or her byzantine scheming (on the able courtier model) brought her down. While Claudius was away in Ostia in 48 AD, Messalina had a party in the palace in the course of which a marriage ceremony was performed (or playacted) between herself and a consul-designate, Caius Silius. Claudius was warned of this by his loyal secretary and seems to have thought that it presaged an attempt to replace him. He ordered the immediate execution of Messalina, Silius, and assorted hangers-on.’ Messalina would then have been about twenty-six.

Messalina has thus come down to us as an archetype of the lascivious woman and femme fatale, a picture of her contributed to in no small measure by Juvenal himself, who devoted a passage to her in the Sixth Satire in which he perpetuated the story that in her attempts to slake her lusts she went so far as to go to work in a brothel. It is to this passage that Beardsley refers in his two drawings, or which, I should say, and as I shall show, he actually and quite particularly illustrates.

The history of the titles

For ease of understanding of the extraordinary confusion here chronicled, I will state that the Tate drawing, the coloured one, depicts Messalina setting out for the brothel, and the V&A drawing shows her return. Also, for the sake of simplicity, I have referred to the drawings as ‘Tate’ or ‘V&A’ although they did not enter those collections until 1928 and 1972 respectively.

Surprisingly, the history of the titling or mistitling of these works begins in Beardsley’s lifetime. In his September 1895 Catalogue of Rare Books 3, Leonard Smithers, Beardsley’s own publisher, presented what is easily identifiable as the Tate drawing, as an ‘Original Unpublished Drawing in Colours’, and titled it Messalina and her Maid Returning from the Lupanar. ‘Lupanar’ is Latin for ‘brothel’. Then, in January 1897 Smithers published the album of Beardsley’s work A Book of Fifty Drawings. This included a so-called ‘iconography’ of Beardsley’s work, actually a pretty bald and irritatingly unnumbered checklist, compiled by his friend the art critic and associate of William Morris, Aymer Vallance. About two-thirds of the way through we find an item ‘Four Designs for the Sixth Satire of Juvenal’. These are clearly the designs made in August 1896 and one of them is given as ‘Messalina returning home’. This must refer to the V&A work both because of its grouping with the August 1896 works and because elsewhere in the overall list, the very last item, in fact, is ‘Messalina returning from the bath. Pen and ink and water colours’. Here ‘bath’ is a euphemism for the Italian bagnio, in turn at that time a common and slightly stronger euphemism for ‘brothel’. Clearly this is the Tate work with its absolutely distinctive watercolour additions. The first of these titles is absolutely accurate as far as it goes, but the drawing it is attached to would, as we shall see, be much better served by the second title which in relation to the Tate drawing is wholly inaccurate. Vallance seems to have thought that both drawings illustrated the same event.

How did Vallance’s error arise? This question is all the more baffling since we know from Beardsley’s letters that he checked a manuscript version of the iconography and made additions to it in late October 1896, and checked a proof in early November, returning it to the publisher, Leonard Smithers, in a letter postmarked 10 November. The answer might lie in the position in the iconography of the Tate drawing – the very last item. In a letter dated by the editors ‘circa 16 November 1896’, Beardsley writes to Smithers: ‘So glad to hear of the iconography, that all goes well with it’. This could imply that additions were still being made. So it could have been added at the last minute without consulting the artist. The reverse of the drawing bears an inscription by Smithers dated 27 April 1898, five weeks or so after Beardsley’s death on 16 March.

In 1898 the International Society of Sculptors Painters and Gravers, whose president was Whistler, held an Exhibition of International Art in London. It opened in May 1898, roughly two months therefore after Beardsley’s death in Menton on 16 March 1898. The exhibition included twenty-nine items by Beardsley, amounting to a mini-retrospective or memorial show. An illustrated catalogue was published in which item 169 is ‘Messalina returning from the bath. Colour’ – clearly the Tate work, although if there were any doubt it is resolved by turning to the illustration of that drawing in the catalogue which is captioned ‘Messalina returning from the bath’. The organisers were evidently following Vallance’s 1897 list and perpetuating his error.

In 1899, the year after Beardsley’s death, a further album, A Second Book of Fifty Drawings was published by Smithers in which both Messalinas were reproduced. There the V&A drawing is titled, correctly now pace the euphemism of ‘bath’, ‘Messalina returning from the bath’ and the Tate drawing simply ‘Messalina’, which again is accurate as far as it goes. Next comes the catalogue of Beardsley’s work first compiled in 1900 by the extraordinary American collector A. E. Gallatin, who as well as large holdings of Beardsley, collected Cézanne, Picasso, Braque and Matisse among others. In the 1903 edition of his catalogue, in which entries are unnumbered, he gives ‘“Messalina” (on staircase)’ and ‘“Messalina” (the drawing in which there is another figure)’. This looks like playing safe, although it seems odd that he ignored the titles given in the Second Book of Fifty Drawings.

In November 1900, presumably postdating the earliest version of Gallatin, John Lane, Beardsley’s publisher in his heyday, issued the second of two compilations of Beardsley’s work, The Later Work of Aubrey Beardsley, in which, following the Second Book of Fifty Drawings, the V&A drawing appears as ‘Messalina Returning from the Bath’ and the Tate one as plain ‘Messalina’. Lane’s volumes were reprinted several times and remained a basic source for Beardsley until the Zatlin catalogue. In 1909 Robert Ross’s monograph, Aubrey Beardsley, appeared. Ross had known Beardsley since February 1892, the very beginning of his career. In Ross’s book, Vallance’s 1897 iconography was republished, extensively revised and now numbered. No. 126 is ‘ “Messalina”, “with another woman on her left, black and white with black background” ’. No. 159 is ‘ “Messalina returning from the bath”. Pen and ink and watercolours’. This ought to refer to the V&A work but Vallance has somehow transferred to it the watercolour additions to the other. Also, remember, he had previously titled the V&A work ‘Messalina Returning Home’. It was obvious that he was hopelessly confused.

In 1923-4, what was then the Tate Gallery held a major Beardsley exhibition, in the catalogue of which the Tate drawing, then still in private hands, is given simply as ‘Messalina’, and the other as ‘Messalina returning from the bath’, so following A Second Book of Fifty Drawings. So far so good. In 1928 the Tate work was acquired with funds from the Duveen Drawings Fund and ‘with the aid of a subscription from AL Assheton’. And then, lo and behold, it appears on the Tate catalogue file with a whole new title, Messalina and her Companion! In 1945 Gallatin published the final definitive version of his Beardsley catalogue. In it item 972 is ‘Messalina, on staircase’, and 951 is ‘Messalina returning from the bath’. So he is now plumping for ‘Messalina returning from the bath’ as the title of at least one of the drawings and decides to apply it to the Tate work.

Now, fast forward to the 1964 Tate catalogue of modern British art, an important milestone in the publication of the Tate Collection and yes, a change of title: the drawing has now become ‘Messalina Returning Home’ and the compilers note ‘The Tate drawing has hitherto been catalogued as “Messalina and her Companion”, but it seems best to return to the title used by Vallance in Fifty Drawings, a publication with which Beardsley himself was associated’. But the drawing clearly described by Vallance as having watercolour additions was titled by him ‘Messalina returning from the bath’! And in any case, Vallance had got it wrong. Not only did the compilers take Vallance on trust, which is sort of forgivable, but they misread him which is less so. Equally less forgivable is that they did not think to look to A Second Book of Fifty Drawings. It is particularly unfortunate that the Tate error was then perpetuated by the revered Beardsley scholar and V&A curator Brian Reade in the catalogue of his legendary 1966 Beardsley exhibition at the V&A, which marked the beginning of the modern revival of Beardsley’s reputation, and in his subsequent book of 1967 which was the first attempt at a fully illustrated catalogue raisonné, and remained the single most important reference work for Beardsley’s art until the publication of Zatlin’s great catalogue in 2016.

The drawings and the text

In the whole history of these two works, what seemed to me to be absolutely astonishing is that, up to the point of my 2002 paper, no one appeared to have thought of getting hold of the Juvenal text, of which there have been many translations, and comparing Beardsley’s drawings with it. If one does the results are both dramatic and fascinating. The references to Messalina in the Sixth Satire appear in a self-contained passage of some eighteen lines. Here they are in the translation by Peter Green (referred to in ‘Sources’ above):

…hear what Claudius

Had to put up with. The minute she heard him snoring,

His wife – that whore empress – who dared to prefer the mattress

Of a stews to her couch in the Palace, called for her hooded

Night-cloak and hastened forth, alone or with a single

Maid to attend her. Then, her black hair hidden

Under an ash-blonde wig, she would make straight for her brothel,

With its odour of stale, warm bedclothes, its empty reserved cell.

Here she would strip off, showing her gilded nipples and

The belly that once housed a prince of the blood. Her door sign

Bore a false name, Lycisca, the ‘Wolf-Girl’. A more than willing

Partner, she took on all comers, for cash, without a break.

Too soon for her the brothel keeper dismissed

His girls. She stayed to the end, always the last to go,

Then trailed away sadly, still with a burning hard on,

Retiring exhausted, yet still far from satisfied, cheeks

Begrimed with lamp-smoke, filthy, carrying home

To her imperial couch the stink of the whorehouse.

As is obvious, in the Tate drawing it’s all there – the night setting, the hooded cloak, the blonde wig over black hair, the attendant maid, but above all this is a magnificent image of a woman dressed up to the nines, setting out on the town, and definitely up for it. How could anyone ever have thought she could be coming home? And equally, in the V&A drawing Beardsley has brilliantly imaged her return, trailing up the palace stairs, clothes and hair dishevelled, her clothes indeed reduced to a mere shift, nipples still erect, grim-faced and, the final nice touch, fist clenched in frustration. So in one drawing, she is going and in the other, she is coming, except that as both Juvenal and Beardsley so vividly tell us, she clearly hasn’t really come at all.