As a teenager, I was fascinated by American horror comics and the complexity of progressive rock – classical forms mixed with odd time signatures and experimental techniques that pushed at compositional boundaries. To me, there is something truly prog about Aubrey Beardsley. It is in the fusion of styles, the merging of high and low cultures, the aesthetic innovation that challenges the notion of correct behaviour whilst remaining focused on artistic credibility.

I am not an art historian or an academic, but if rock music can aspire to the condition of art, then it aligns with Walter Pater’s view that ‘all art aspires to the condition of music’, its continuous movement.[1] We can each sharpen our critical thinking, but when it comes to any medium that relies on a message being conveyed by abstract as well as narrative ideas, intuition is a much-underrated tool. Before I went to this exhibition, I had not heard of Walter Pater, believing I had come up with the condition of art/music concept myself. But that is the intuition for you, a tangled and yet specific response, not exactly a chance happening as Francis Bacon would have it, but a blurring of ideas, formal distinctions and what we might call common sense. Something that extends towards an augmented truth perhaps, if you believe truth is conceptual and highly personal. So far, so very prog – the artist happily wearing his influences (Cranach, Blake, Rococo, the Floating World) but looking for the change, typically starting with themes of classical literature, fantasy, folklore and social commentary, with the added theatrics of erotica and the grotesque. I don’t feel that Beardsley is reactionary so much as divergent and I love him for it.

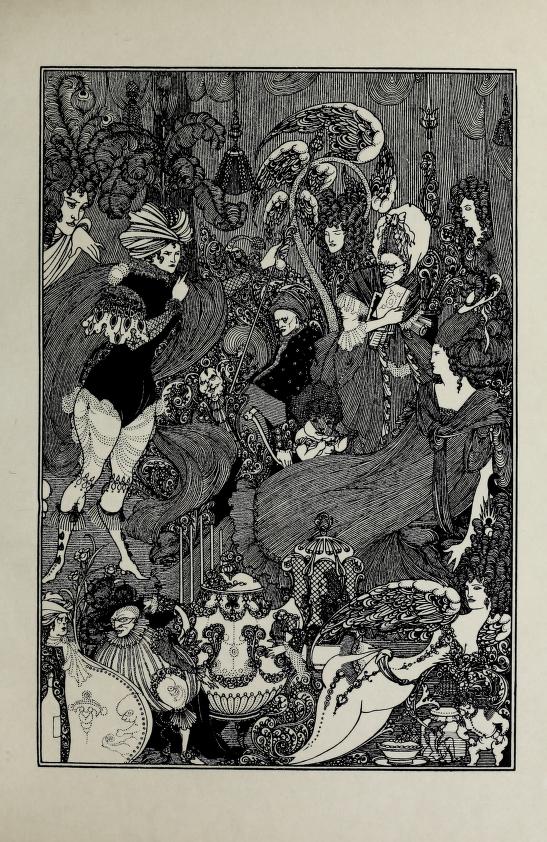

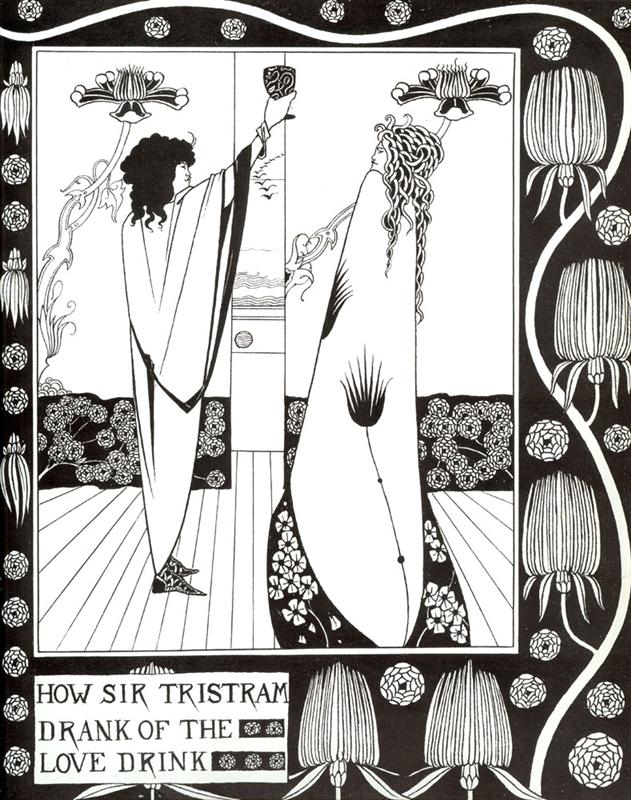

I have only seen Beardsley’s work, as was originally intended, in print form. Standing in front of Le Morte Darthur at the beginning of the exhibition was (if you can excuse the hyperbole) enchanting. It is not just the audacity of the image-making (part illuminated manuscript, part comic book), it is the obvious shift towards what we might now think of as graphic design, the combination of visual elements – drawings, borders, chapter headings – that create the sense of something classical yet progressive. Intricate symbolism with archetypes but no sentimentality. From a contemporary perspective, you feel, even as a non-expert, that this is a point of departure, the formulation of a proposition that is also at the heart of the Arts and Craft Movement, the Vienna Secession and yes, Biba. It is right there in the radical imagination, the focus on the story, the decorative sequential panels and repeating patterns – the continuous movement. Beardsley may work in black and white but he does not leave gaps.

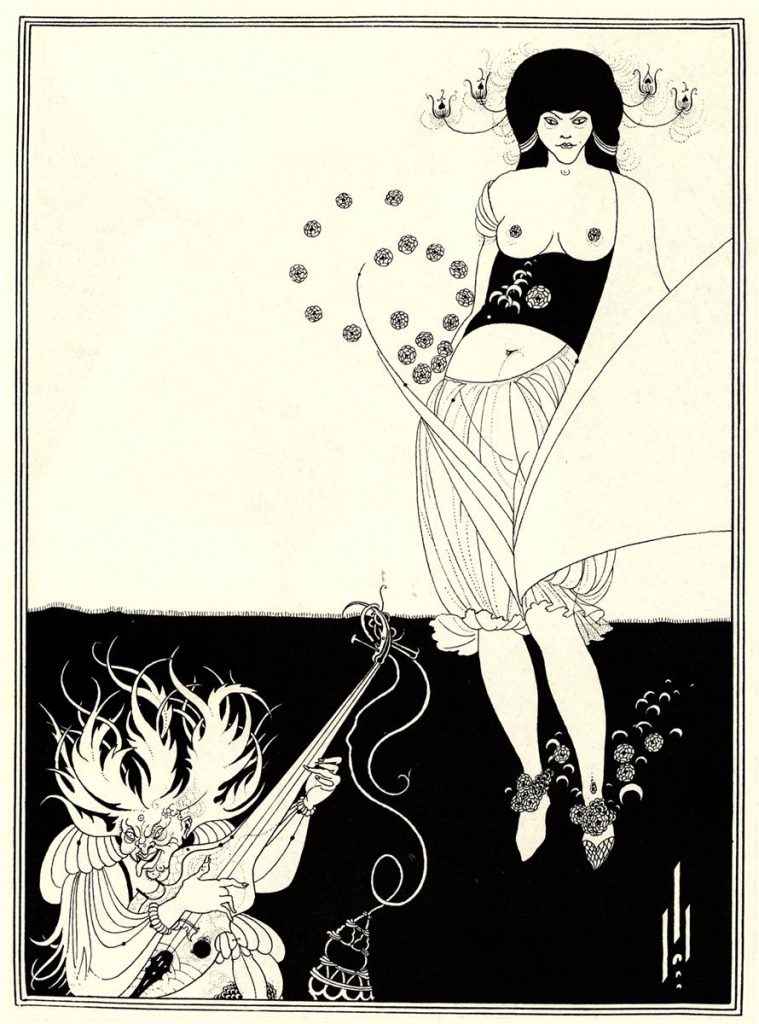

So, I think a lot about music and the afterlife of Beardsley’s work in music, including in the visual concepts of bands who became as well known for art direction as anything they committed to vinyl. I am trying not to speed up as I near the Salome room, but inevitably I do speed up because it is A DESTINATION. And maybe, since I am neither an art historian nor an academic, I can get away with saying, it’s just so great (clapping my hands like a greedy child wanting ice cream). I discover from a quick Google search that it was Joseph Conrad and not Susan Sontag who said, ‘A work that aspires, however humbly, to the condition of art should carry its justification in every line’.[2] It is that emphasis on ‘every line’ which seems so particular to Aubrey Beardsley at that moment and which for me elevates these images above the play. Without the distraction of colour, apart from the background colouring of the gallery walls, the attention is all on the compositional elements – the shape and texture – the story at work in ‘every line’ like a series of devilish fashion plates.

OK, I am a fan of Beardsley’s obsessive dedication, therefore it seems counterintuitive to say that I also got a bit exhausted (too much ice-cream and I still had The Rape of the Lock and Lysistrata to see). It is ample that so much of Beardsley’s work has been collected in one place and that his own fatigue is palpable in some of his later, lesser-known works (unlikable and oddly appropriate). You cannot get away from the presence of disease, not in the continuous references to Beardsley’s own terminal condition, nor in the collective psyche of his audience. But, like an overlong drum solo, I could have done without the room dedicated to Beardsley’s buddies (a distraction) and also the push at the end of the exhibition to show us just how much Beardsley has influenced everything from modern art and graphic design to psychedelia. ‘Truths’ better left for the individual perhaps (and an actual assault on the senses, being mostly in colour). As someone probably said to Rick Wakeman as he dragged another keyboard into the studio, there is already enough to love.

[1] Walter Pater, The Renaissance. Studies in Art and Poetry (London: Macmillan, 1893), p. 141.

[2] Joseph Conrad, The Nigger of the Narcissus (New York: Doubleday, Page & Co, 1914), p. vii.