After a brief opening in March, visitors can now enjoy this exhibition until 20th September. Anyone whose youthful imagination thrived on Beardsley’s strange and beautiful work should explore it in reality in the close and intimate encounter paradoxically made possible by current social distancing and managed entries at the gallery. This rare opportunity is unlikely to occur again soon. The title of the exhibition consists simply of the artist’s name, suggesting that the exhibition provides a comprehensive and definitive account of his life, work, and legacy. What conclusions then might the visitor draw, and would these be fair and accurate reflections of Beardsley’s short but intense career?

The exhibition demonstrates what once kept Beardsley on the margins of art history. He had, of necessity, an eye to the commercial opportunities which would set him free from the drudgery of his job as an insurance clerk, a period which ended with his first work for publisher J.M. Dent in 1892, illustrations for Malory’s Morte Darthur. Commissions to illustrate books, periodicals and posters followed. As designs for reproduction, their utility and small scale barred Beardsley from those elysian heights reserved by the art establishment for fine art practitioners. But they endure as a measure of his unique artistic response to culturally significant subjects which subverted the norms and values of his time. Under the smokescreen of beautiful and florid embellishment, he invariably challenged the limits of what could or should be published. The eye is cajoled by intricate inventions, perverse botanical forms that defy gravity, their abstraction concealing other daring suggestions of phallic shapes to outwit the unwary observer and the inattentive publisher. Beardsley, we are told, specialised in the ‘spatial ambiguity’ whereby ‘flat pattern or three-dimensional space’ is difficult to ascertain.

The hazards and unreliability of commissions against the backdrop of negative publicity form a subtext in the Beardsley exhibition. The unfortunate association with Oscar Wilde’s trial for ‘gross indecency’ hinged on press reports that, on the evening of his arrest, Wilde was carrying a yellow book which was assumed to be The Yellow Book, the periodical then edited by Beardsley. Publishers took fright and Beardsley was forced to seek new opportunities.

Beardsley’s work connects varied artists and techniques; for example, his early references to Symbolist paintings by Gustave Moreau or to the Japanese prints associated with Mary Cassatt, the Impressionists, and Whistler all contribute to something entirely his own. Beardsley caricatured Whistler, whose Peacock Room commission ‘captivated’ him. Coincidentally, the V&A is currently reopening its installation of Darren Waterston’s Peacock Room reinterpretation, Filthy Lucre, with its more sinister configuration.

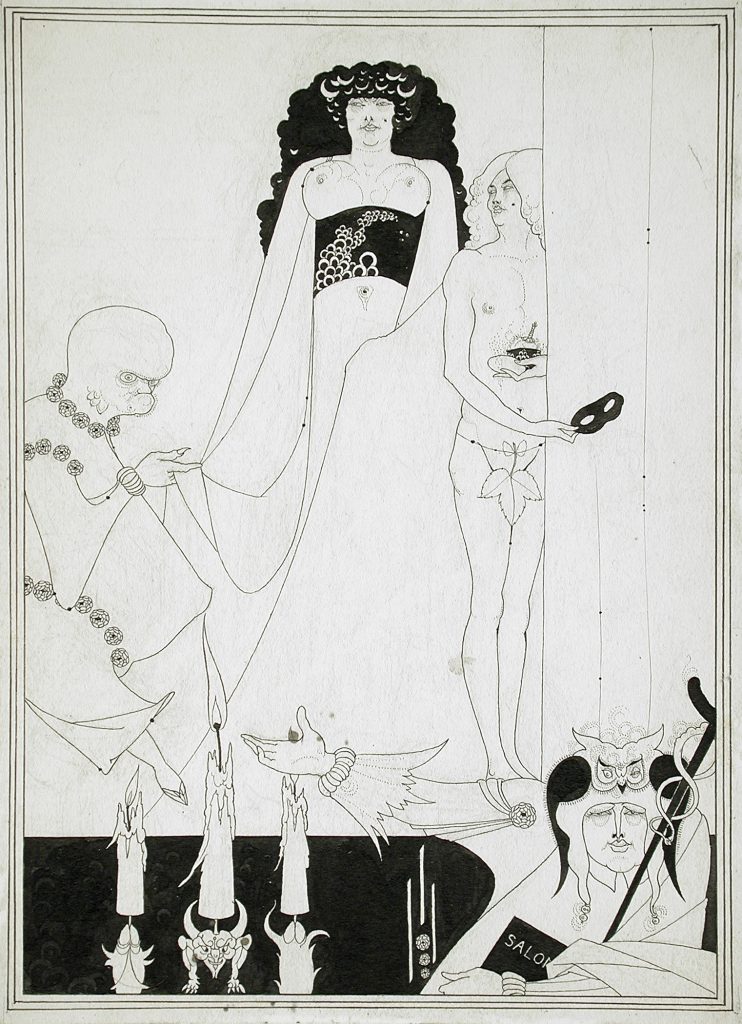

The exhibition frames the range of Beardsley’s drawings and prints as part of a broader cultural climate. His own reading was eclectic and prolific. He illustrated not only Oscar Wilde’s work but books in the Keynotes series, such as George Egerton’s short stories (1893). He introduced a ‘key’ motif to connect different volumes in the series. This motif would have been understood by readers, an exhibition label informs us, as a sign of the contemporary debate whether young unmarried women should have their own house keys, a potent symbol of freedom. That this access to unregulated movement was a matter of controversy reminds us that Beardsley’s career coincided with the era’s deep fear of the sexually powerful and independent woman, the emerging ‘New Woman’ overlapping with the femme fatale archetype.

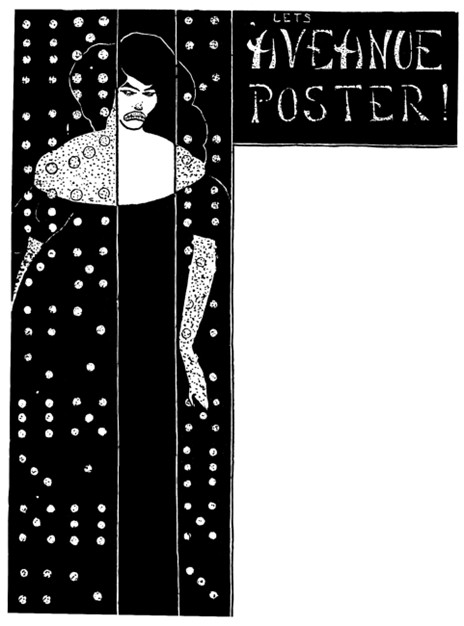

The female figures of Beardsley’s oeuvre are rarely delicate, benign or submissive, and neither conventionally beautiful nor vacuous. One objection to his poster for A Comedy of Sighs at the Avenue Theatre in 1894 was that the depicted woman was too ugly.[1] Brooding, malignant and determined, Beardsley’s women often engage with the world with imperious hauteur. Arrogant pomposity and bizarre eccentricity define many of the male characters, if it is possible to summarise the visual impact of the dozens of images on show. The visitor, fatigued by their sheer volume throughout the fifteen sections of the exhibition, may well leave with this impression.

Beardsley’s own strangely haunting oil paintings Caprice and Masked Woman with a White Mouse on the verso (c.1894), which were not shown in public during his lifetime, are included in the exhibition. There are the familiar portraits of him by Walter Sickert (1894) and Jacques-Émile Blanche (1895). Blanche’s elegant depiction shows Beardsley sartorially emulating the Parisian dandy. In a curtained ‘shrine’ to his talent, it is placed above his writing desk, on which several prints and his silver and ivory paper-knife are strewn. The psychotropic orange walls replicate a colour Beardsley decided on for his home in Pimlico, based on that chosen for his library by the eccentric character Des Esseintes in Joris-Karl Huysmans’ novel A Rebours (1884). Huysmans described it as ‘that most morbid and irritating of colours, with its acid glow and unnatural splendour’.[2] We learn that, like Des Esseintes, Beardsley preferred to work by candlelight with the curtains drawn. Instead of Blanche’s companion portrait of Beardsley’s sister, the striking canvas by Oswald Birley Mabel Beardsley as a Page (1910) adds one of the few naturalistic female representations in the exhibition. Her life and theatrical career linger on the boundaries of our knowledge about her brother. Anecdotally, it was the sight of Mabel’s luxurious Pre-Raphaelite red hair that prompted Edward-Burne Jones to first admit the brother and sister to his studio, an occasion which enabled him to examine Beardsley’s portfolio and subsequently to recommend him to take up art classes. One small photograph of Beardsley’s mother bears witness to the other woman in his life who tenderly cared for him to the end.

The exhibition incorporates a 1923 film clip of Alla Nazimova’s adaptation of Salome along with objects and images in the final room to demonstrate the longevity of Beardsley’s influence across the arts, his inspiration for other artists or designers as a ‘cult’ figure whose style slipped easily into myriad manifestations of the bohemian way of life. His expressive lines could be reduced to a cypher for commercial purposes, captured in a calligraphic flourish and exotic curlicue, a trailing peacock tail picked out in black. Recognisable Beardsley style details have become signifiers for a heady mix of fantasy, decadence and sexual obsession, regularly invoked in counter-culture imagery. The exhibition documents the development of this afterlife in the final sections, ‘After Beardsley – The Early Years’ and ‘After Beardsley – The Sixties’ when the 1966 V&A exhibition brought his art back into the public eye. As Kenneth Clark put it, ‘No wonder Beardsley’s drawings became a kind of catmint to adolescents’.[3]

The most erotic drawings are displayed in a room signposted with a warning, and we enter furtively as if invited into a private study, male guests only. In the next room, Gerald Scarfe’s 1967 ink drawing Aubrey Beardsley parodies the ‘curiosa’ we have just viewed. Covered by a small curtain designed to protect the susceptible visitor, it continues the analogy of privileged viewing and prompts an association with the concealment deemed necessary by different owners of Gustave Courbet’s L’Origine du Monde (1866) or with the provocatively curtained painting on the wall in Hogarth’s Marriage A La Mode (Plate 2, 1743-1745). Beardsley’s erotic works were unknown to enthusiasts in the years shortly after his death. In fact, a 1918 manual for fashion illustrators promotes the study of his technique, using his plates Third Tableau of Das Rheingold (1896) and The Ascension of St. Rose of Lima (1896) as examples, with no indication of the context of these as illustrations for his unfinished erotic novel Under The Hill which first appeared in expurgated form in The Savoy magazine in 1896.

The exhibition presents Beardsley as both a man of his time and a singularly innovative artist, part of a creative milieu but also standing outside, vulnerable and destined for a tragic early death from tuberculosis. If the 1920s and 1960s were self-consciously modern decades in which Beardsley could be reshaped and reinvented, will the 2020s be able to provide another rebirth for his expressive line? Is the full narrative of his life and work at Tate Britain the definitive one? It does not seek to compare or judge him and the parodies and fakes in the final room encourage us to go back to his original work, however well we thought we knew his style. The rich variety of Beardsley’s output is presented with careful planning and flair, though the record sleeve graphics based on his art may linger in the mind as we leave. The exhibition should inspire us to explore further. In particular, reading more of Beardsley’s under-represented prose and poetry would add to the immensely pleasurable experience of examining his drawings and prints at Tate Britain and ‘vindicate [his] genius as a man of letters and an exponent of pure form’.[4]

[1] ‘Ars Postera’, Punch, 21 April 1894, p. 189.

[2] Joris-Karl Huysmans, Against Nature, trans. by Robert Baldick (London: Penguin Books, 2003), p. 16.

[3] Kenneth Clark, ‘Out of the Black Lake’, Sunday Times, 8 May, 1966.

[4] Aubrey Beardsley, Under The Hill, completed by John Glassco (Paris: The Olympia Press, 1959), p. 9.