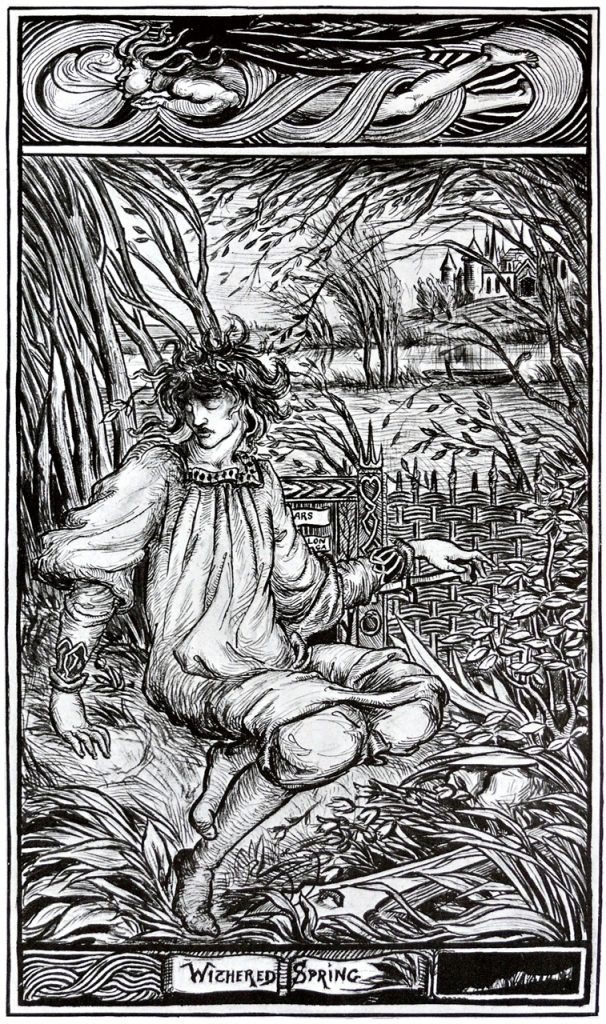

Given that Aubrey Beardsley died of tuberculosis in 1898 at the age of only twenty-five, the question of how the exhibition of his work currently running at Tate Britain in London deals with the subject of his impairment and early death is an important one. Beardsley was diagnosed with what was then an incurable illness at the age of seven, and thus he always knew that his life would be a brief one. As the sheer volume of material in the exhibition testifies, this seems to have spurred him on to pack as much into his life as he possibly could. That the exhibition’s curators have decided on this interpretation is evident from early on the exhibition: one of the first artworks on display is ‘Withered Spring’, a graphite drawing from 1891, which includes the partially-obscured description ‘Ars Longa, Vita Brevis’ (‘Art Endures, But Life is Short’), which, we are told in the accompanying description, must have had personal resonance for Beardsley.

If this had been the exhibition’s only acknowledgement of Beardsley’s fate, it would certainly have been insufficient for a Disability Studies perspective. Some years ago, the US Disability Studies academic Elizabeth Donaldson commanded that there should be ‘No crying in Disability Studies!’[1], and it seems appropriate to bear this in mind when considering Beardsley’s brief life. The disability movement seeks equality for disabled people, and dismissing someone with a few well-worn platitudes designed both to make one appear to be deeply understanding and to provide a feeling that one has ‘ticked that box’, is definitely not the kind of approach likely to promote equality. A Disability Studies perspective requires that, in Beardsley’s case, his illness and early death are confronted head-on, and shown to have been components of his identity, rather than being sentimentalised. As I will discuss, I feel that the Tate exhibition really succeeds at this. I do feel, however, that other aspects of Disability Studies (most notably intersectionality, which I will discuss below) are not fully explored. I am going to look at this from a number of different perspectives, beginning with Beardsley’s self-image and his development as a dandy.

Beardsley and His Self-Image

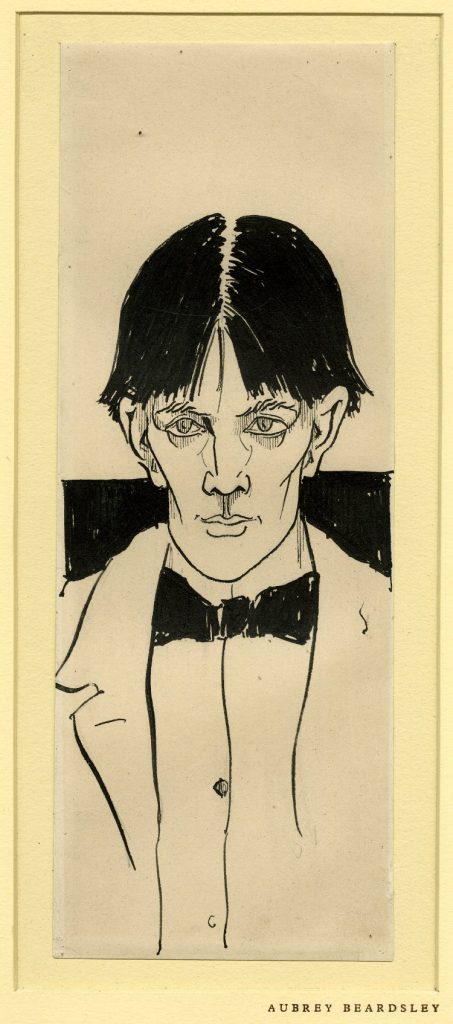

One self-portrait of Beardsley, from 1892 when he was nineteen years old, shows that he already had his own distinctive style, with a high collar, large bow-tie, and his hair in a centre-parting. The description accompanying the self-portrait, like the description accompanying the picture ‘Withered Spring’, tells us that Beardsley knew that his life would be short, and that as a result he worked at ‘a hectic pace’. It is not, however, the mere fact of Beardsley’s prodigious output which is noteworthy, but also the kind of art which he produced, and, indeed, the way he used his height and his extreme thinness (the latter being a result of his tuberculosis) as part of his distinctive style.

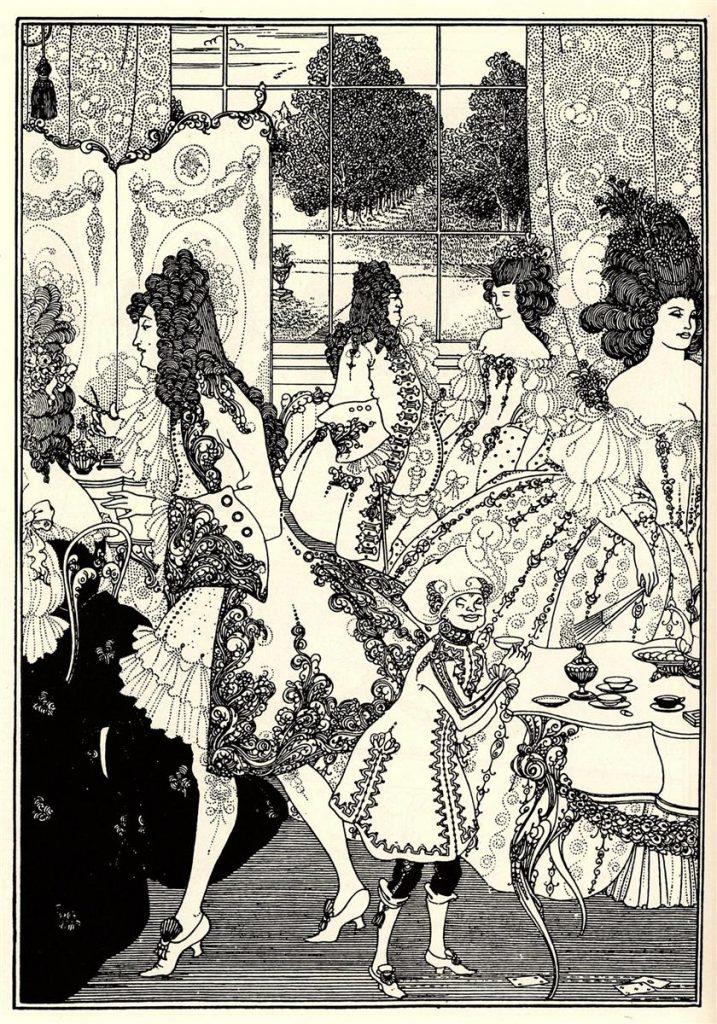

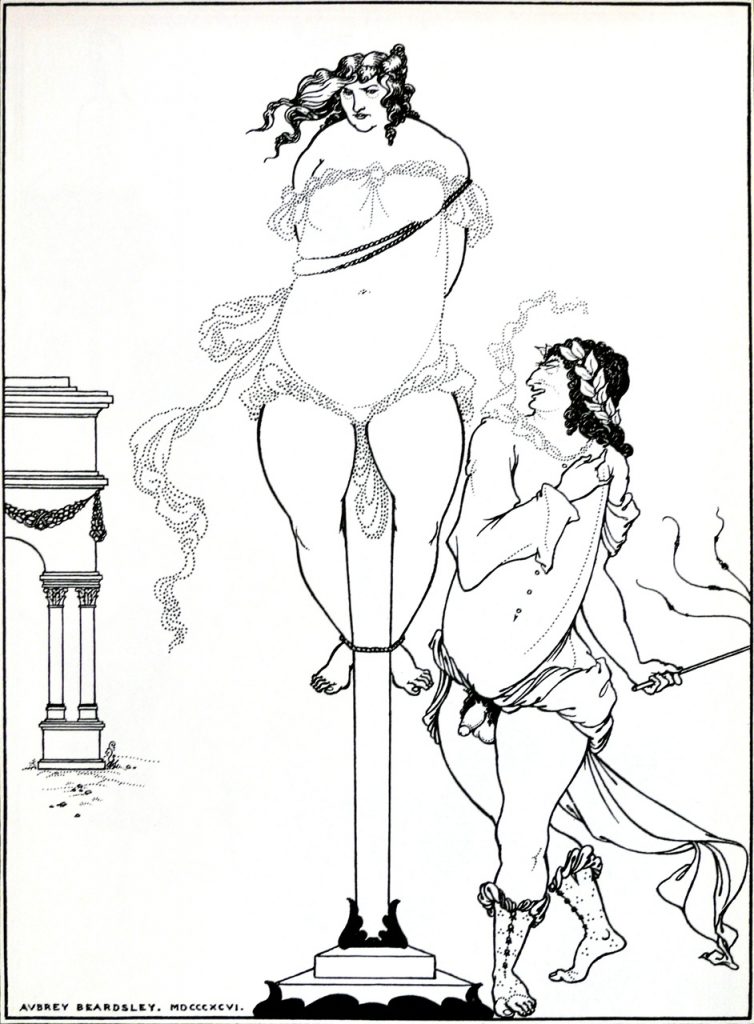

A short film on the Tate’s website is entitled ‘The Art of Being a Dandy’, and makes it clear that Beardsley’s image came partly from having come of age in the 1890s – an era in which there was a widespread fear that, after the enormous social and technological changes that had taken place during the nineteenth century that civilisation had reached its peak and would inevitably crumble. In response to these fears, many artistic people took refuge in ‘Decadence’ – as exemplified by self-indulgence, refinement and a love of the bizarre, and shown best by Beardsley’s own distinctive black-and-white drawings. The film draws a link between the era in which Beardsley came of age, and his dandyism – the exhibition’s curator Stephen Calloway quotes Charles Baudelaire’s claim that dandyism was ‘the last spark of heroism amid decadence’. In addition, the film shows Beardsley’s distinctive image as a matter of personal choice, and it may be seen as a desire to control his own narrative. Both of these motivations are on display in the Beardsley artwork chosen for the Tate’s exhibition. Beardsley’s desire to shock is apparent in many of his works – for example, as he became bored with his commission illustrating Sir Thomas Malory’s Morte d’Arthur, obscene and fantastical images began to appear in the illustrations Beardsley was supposed to be producing. This led his publisher, J.M. Dent, to commission him to create ‘grotesques’ to illustrate the Bon-Mots – three miniature volumes of witty sayings. ‘Grotesque’ was defined as ‘distortion or exaggeration of form to create an effect of fantasy or strangeness’. The accompanying description tells us that this idea was central to the way Beardsley saw himself, and quotes him as saying, ‘If I am not grotesque, I am nothing’.

Beardsley and Intersectionality

‘Intersectionality’ essentially means the use of insights gained from one’s own experience of minority identity to identify with the experiences of others whose own minority identity can in some respects be seen as mirroring one’s own. The most obvious example as far as Beardsley is concerned is that of his interest in, and possible identification with, artistic people who died early from tuberculosis. To this end, the exhibition shows Beardsley’s own portraits of the composers Carl Maria von Weber (1786–1826) and Frédéric Chopin (1810–49), as well as an 1894 portrait by Walter Sickert of Beardsley in Hampstead churchyard following a ceremony to unveil a bust to the poet John Keats (1795–1821). With regard to the latter, the description accompanying the portrait states: ‘Keats had died young from tuberculosis. The parallel between the poet and the artist cannot have been lost on those friends who, like Sickert, knew of Beardsley’s condition.’ In addition, the exhibition includes an illustration by Beardsley for Alexandre Dumas’ story La Dame aux Camélias (‘The Lady of the Camellias’). This illustration was published in the journal ‘The Yellow Book’, of which Beardsley was art editor from 1894 to 1895, and the description accompanying the illustration speculates that Beardsley may have felt an affinity with the story due to the fact that the titular Lady, like Beardsley himself, had tuberculosis.

There are two other ‘impairment’ examples in the exhibition – firstly, Beardsley’s use of people of restricted growth, and, secondly, his illustration of The Rape of the Lock by the disabled poet Alexander Pope (1688–1744).

Beardsley and ‘Dwarves’

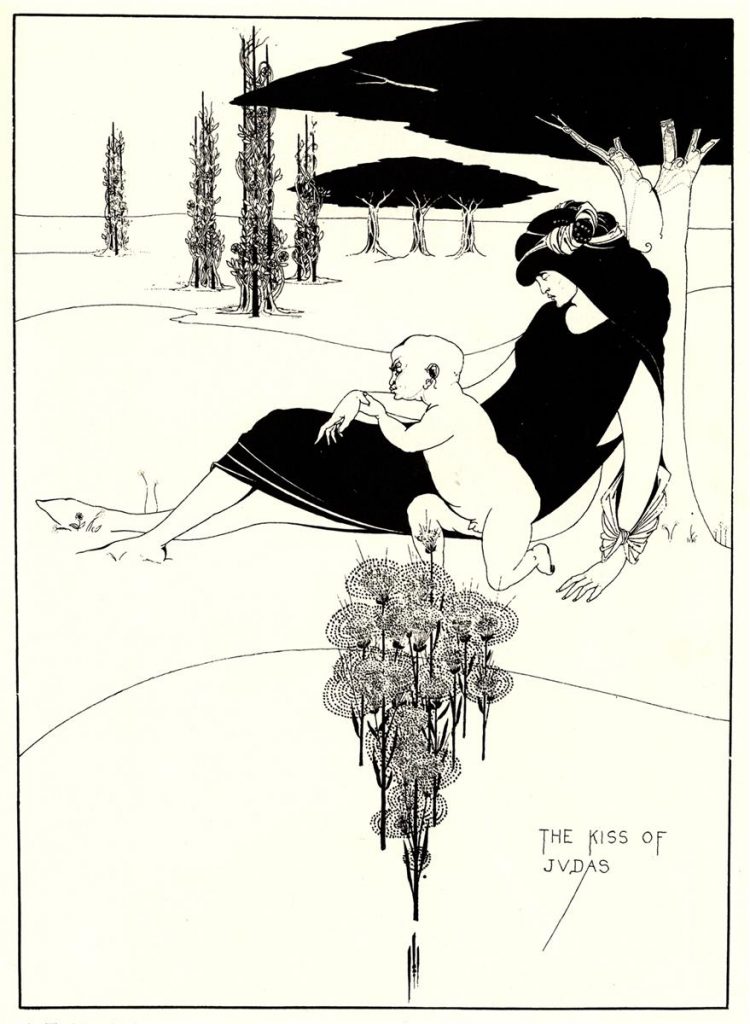

Beardsley’s use of the grotesque is one indication that his own art did not strive for naturalism, and that consequently, just because his oeuvre contains a number of what appear to be depictions of people of restricted growth, it does not necessarily follow that he had any particular views on the subject. Nevertheless, the curators point out that, in Beardsley’s lifetime, people of restricted growth were frequently the targets of other people’s stereotyped views.

The curators’ awareness of this is particularly evident in two places. The exhibition includes Alla Nazimova’s six-minute film adaptation from 1923 of Oscar Wilde’s Salomé, which Beardsley famously illustrated. Of course, as Beardsley had been dead for over twenty years by the time the film was released, he cannot have had any direct involvement in it. Nevertheless, the film’s credits describe the costumes as being ‘after Aubrey Beardsley’. The curatorial description tells us that the film ‘perpetuates some demeaning stereotypes that were current during Beardsley’s lifetime and beyond. This is reflected in particular in the portrayal of the musicians with dwarfism. At that time people with restricted growth were widely associated with servitude and treated as a source of spectacle’. With regard to Beardsley’s illustrations for the horror story The Kiss of Judas, one of which appears to depict a person of restricted growth, the description reiterates previous points about the low estimation in which such people were held, and adds that, at the time, they were predominantly regarded as sources of entertainment at freak shows and carnivals. The curators also state that ‘these offensive attitudes almost certainly influenced Beardsley’s imagery to some extent’.

Frustratingly, however, no clues are offered as to what this ‘influence’ might have entailed. Did Beardsley unquestioningly accept the view of those around him, that ‘dwarves’ were not equals but mere figures of fun, or did he identify that, just as he wished to be in charge of his own self-image, a ‘dwarf’ might want to be in charge of his or hers?

Alexander Pope

A similar question exists with regard to Beardsley’s illustration of the poem The Rape of the Lock, by the disabled poet Alexander Pope. Though the visitor is made aware that one of these illustrations depicts what appears to be a person with dwarfism, the exhibition makes no mention of Pope’s own disability (tuberculosis of the spine known as Pott’s Disease), and if Beardsley either did not know this, or felt no affinity with Pope because of it, it is right that the exhibition did not try to make something out of nothing.

It is an interesting question, however – particularly as Pope also had a form of tuberculosis, albeit one that would not cause premature death. The exhibition’s apparent presumption that there are limits to intersectionality is a fascinating one, and it is instructive to consider examples from the show which do not involve disability, but rather aspects of gender solidarity. One question addressed in the exhibition is: did Beardsley show any signs of misogyny? Although the exhibition shows that he provided illustrations for Aristophanes’ play Lysistrata and drew Juvenal scourging a woman, it is also noteworthy that his closest confidante and main correspondent was his sister Mabel. In addition, his illustrations often addressed aspects of ‘The Woman Question’, and do not appear to have been unsympathetic.

Beardsley’s Early Death

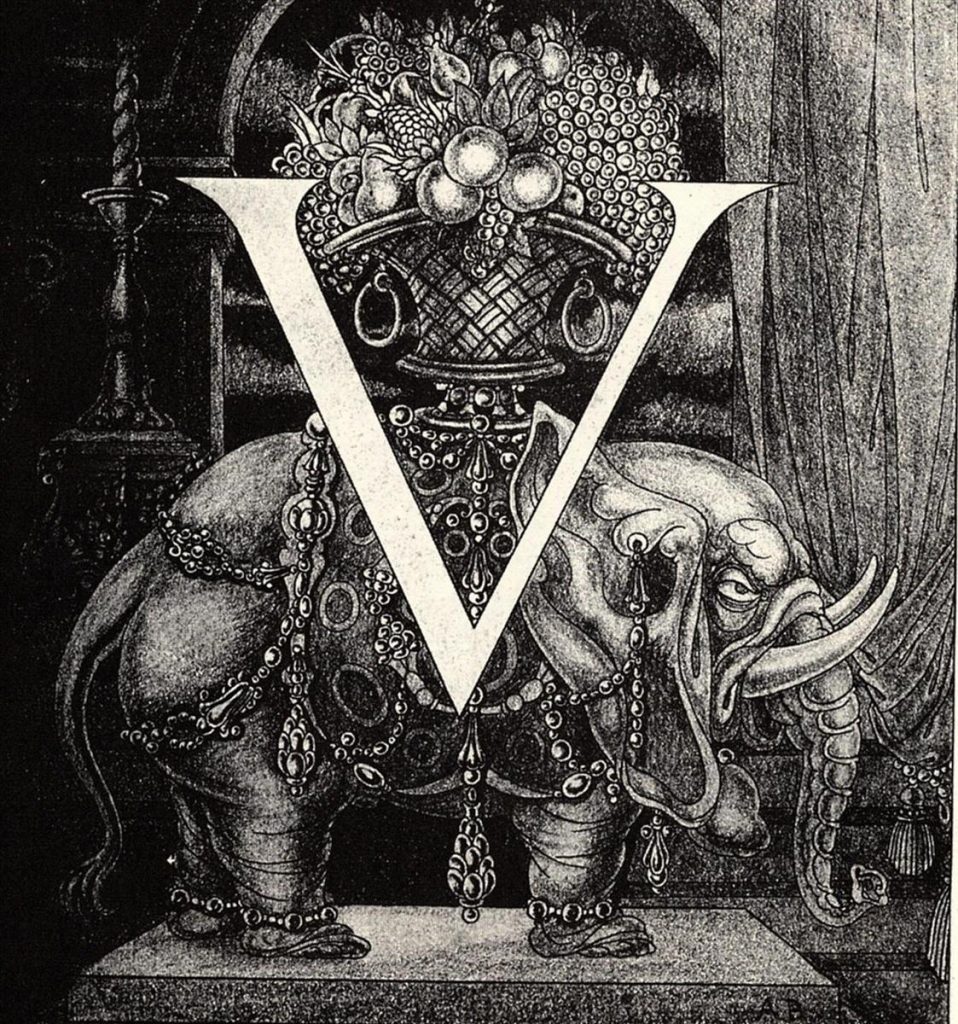

I said above that the Tate exhibition is very successful in the way it discusses Beardsley’s almost lifelong illness and early death, and this extends to offering two different views of whether or not his untimely death should be seen as a tragedy. Outside the final room of the exhibition is a quotation from Oscar Wilde, in which he says of Beardsley: ’there is something macabre and tragic in the fact that one who added another terror to life should have died at the age of a flower’. On the other hand, the final room of the exhibition also contains a quote from Robert Ross, Oscar Wilde’s first male lover, who stated that if Beardsley had lived longer, he might have repeated his achievements, but would not have surpassed them. Of course, though, we will never know. This seems to be acknowledged by the exhibition, which shows that Beardsley’s final commission – which he did not live to complete – was a series of twenty-four illustrations for Ben Jonson’s early seventeenth century play Volpone. The final illustration that Beardsley completed is accompanied by the following curatorial description: ‘It poignantly shows that Beardsley’s imagination and stylistic development continued even as his health was declining’.

[1] Elizabeth J. Donaldson and Catherine Prendergast, ‘Introduction: Disability and Emotion: ‘There’s No Crying in Disability Studies!’, JLCDS, (5) (2), 129-135 (P.129).