The cultural phenomenon known as Fin de siècle or Decadence contributed many new voices to cultures of sexual difference and dissidence. The continuing relevance of these voices results from the mutual inspiration and recognition, by which they eventually transformed the work done by queer people of the past into the heritage of future generations. The queer sensibility, by developing its language of ‘queer codes’, simultaneously learns from its precursors and finds a way to create new communities.

Recognising that historical identities do not have exact counterparts in the present but are instead very loosely related to contemporary queer identities and social politics, I use the term ‘queer’ in the sense elaborated by Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick: ‘the open mesh of possibilities, gaps, overlaps, dissonances and resonances, lapses and excesses of meaning when the constituent elements of anyone’s gender, of anyone’s sexuality aren’t made (or can’t be made) to signify monolithically’.[1] As to the use of the term in the field of history, I share the stance of Kathryn Kent, who describes ‘queer’ as ‘a more encompassing and therefore more transhistoric term that may include any act or proto-identity that exists outside the realm of bourgeois, heteronormative reproduction and its correlative ideology of gender roles […] a term that is simultaneously oppositional and nonspecific’.[2]

This essay aims to analyse and characterise the specific sensibility in the works of two queer artists, Aubrey Beardsley (1872–1898) and Konstantin Somov (1869–1939). Bearing in mind the socio-historical and cultural context of the selected works, I aim to outline the continuous relevance of their aesthetics and symbolism, primarily from the perspective of queer studies and partly queer historicism. The analysis of selected artworks is comparative, in part using Somov’s private journals to ‘de-code’ the imagery drawn on by both artists.

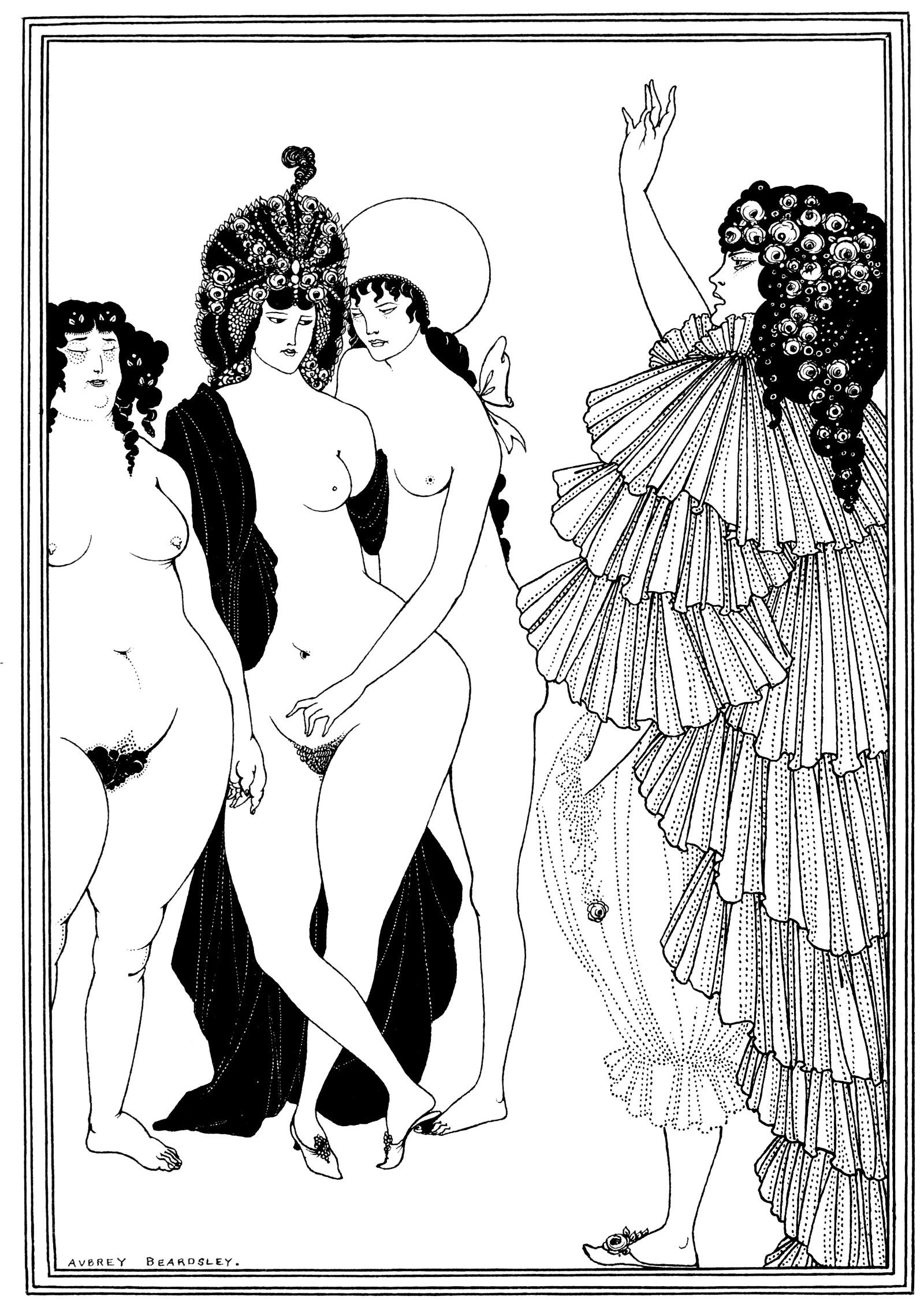

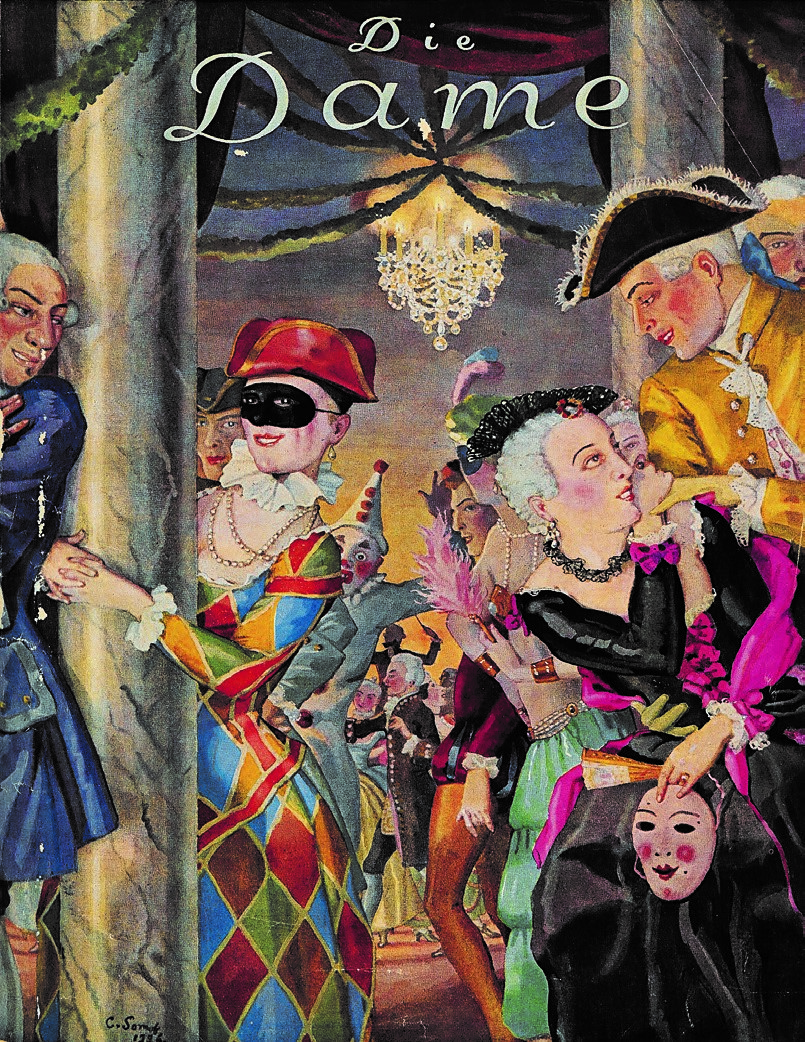

Queer individuals find great comfort in imagining utopian worlds, which bring hope for queer futurity.[3] The Decadents developed a queer fantasy basing on and reinventing a past era — Rococo.[4] Consequently, Rococo aesthetics was one of the central sources of inspiration for Beardsley and Somov. It may be explained, to some extent, by the fact that both artists read and illustrated eighteenth-century texts: Somov — The Story of the Chevalier des Grieux and Manon Lescaut by Antoine Prévost, and The Book of the Marquise (a selection of eighteenth-century French erotic literature arranged by Franz Blei in the 1907 edition and by Somov himself in the edition of 1918), Beardsley — The Rape of the Lock. However, Rococo also appears in the works of both artists when the context does not require it. Beardsley depicts rococo scenes on the covers of The Savoy and the ruffles, wigs, and stockings associated with Rococo fashion in the illustrations to the ancient Greek comedy Lysistrata by Aristophanes, while Somov creates separate pieces inspired by this style: for instance, The Masquerade in the Eighteenth Century, Pierrot and the Lady.

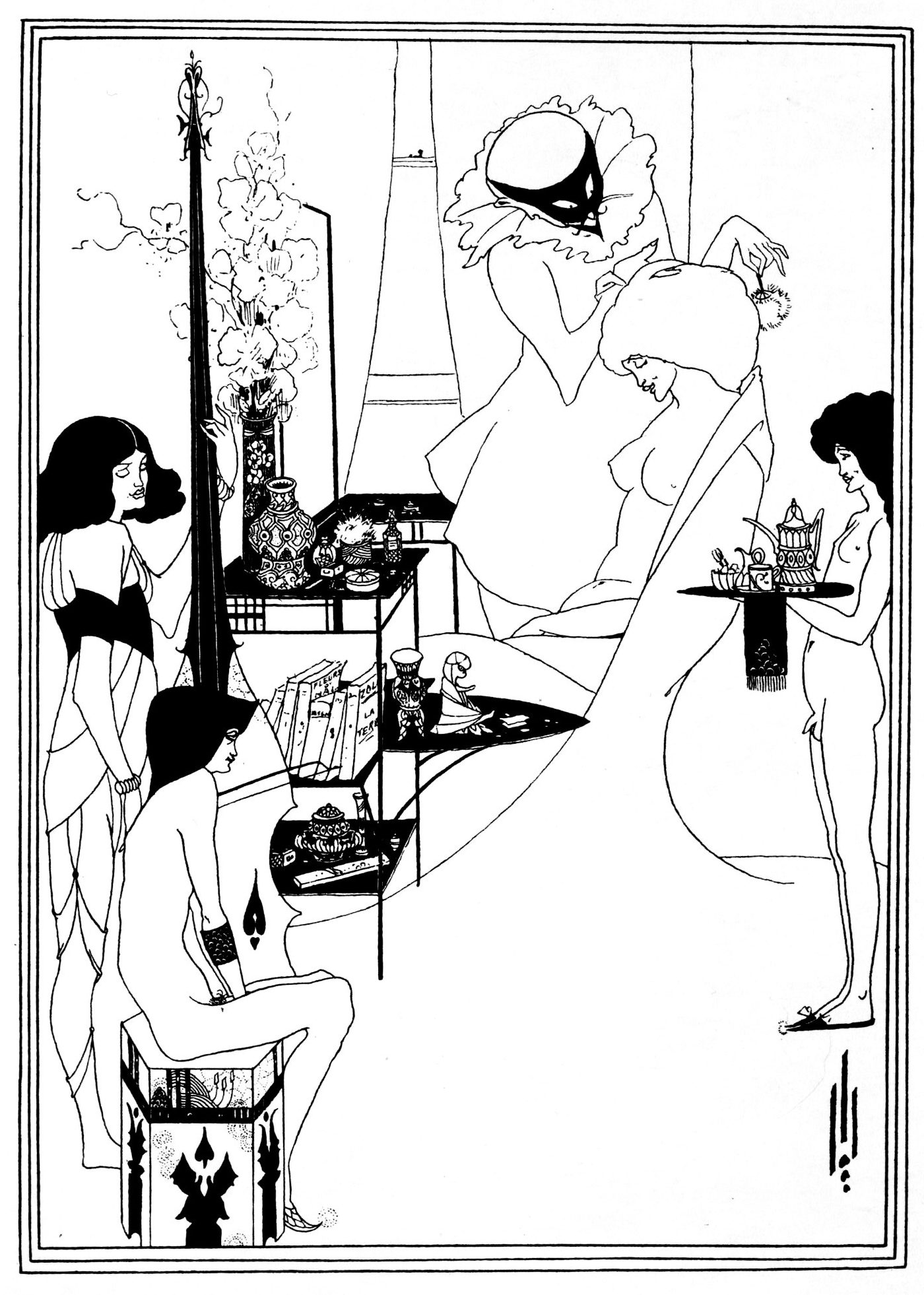

In the minds and works of these artists, Rococo is not a closed and finite historical period, but a lively and sensual world of imagination, an idyll and the complete opposite of the contemporary reality. For both artists, Rococo was associated with frivolity, liberation, sexuality, desire, and masquerade. This connection is suggested by the very canon of Rococo painting, where the fête galante is a common motif. It was arguably one of the main inspirations behind Beardsley’s unfinished erotic novel, The Story of Venus and Tannhäuser, or Under the Hill, which the artist worked on while preparing illustrations for the Rape of the Lock.[5] The precision, detail, visuality, and sensuality of his literary style are in complete accord with his artworks; the artist approaches, in a way, the concept of Gesamtkunstwerk, popularised by Wagner. In Beardsley’s illustration for Under the Hill, The Abbé, the main character in the story is aesthetically sophisticated; his hair resembles a wig; Malcolm Easton also acknowledges his feminine physique.[6] Both here and in The Battle of the Beaux and the Belles in The Rape of the Lock, there is little importance attached to correlation between gender and the respective degree of decoration in the appearance of the characters.

Somov’s Picnic, created for The Book of the Marquise, clearly mimics the Beardsleyesque rococo while using similar imagery, abundant ornamental greenery and a type of Rococo woman that is a recurring character for both artists. The Rococo ladies are a recurring character type for both artists. The key to finding the subtextual meaning attached to them might be found in Somov’s diaries. Somov mentions that his contemporaries were perplexed as to why he portrays women and heterosexual couples so often despite his homosexuality, and so they speculated on the subject. Benois argued that Somov was ‘attracted to ugly women’ and ‘mocked them’, and Bakst doubted Somov’s homosexuality.[7] But according to the artist himself, the heroines of his paintings were ‘a reflection of [his] soul, [his] attraction to men’.[8] Somov further describes the essence of his work: ‘art, artworks, my favourite paintings and sculptures are, for me, closely related to gender and my sensuality above all’.[9]

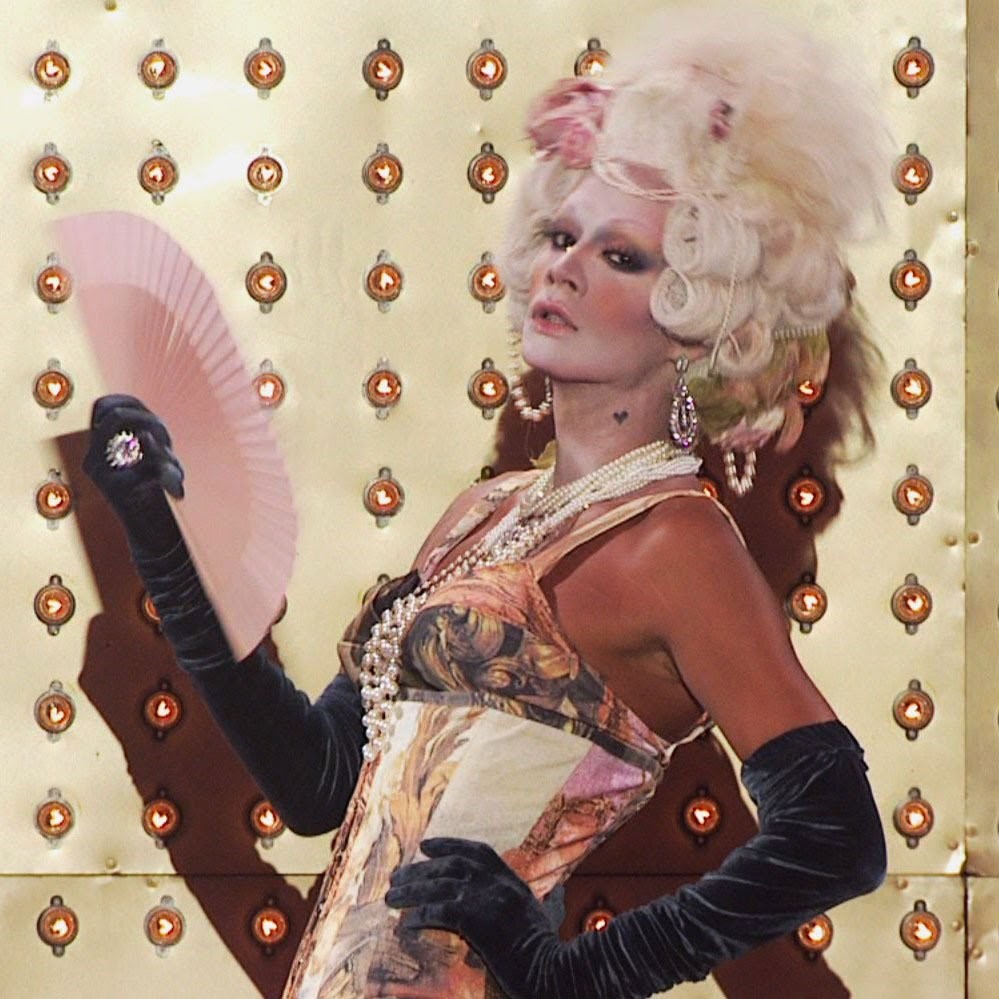

Somov’s comments suggest how in his oeuvre, and Beardsley’s as well, a queer sign or even a queer code manifests itself. A motif, here the ‘heroines’ of his art, becomes a code related to a non-normative identity or way of life when it is continually and steadily used. The figure of the Rococo woman is one of the most widespread archetypes both in queer societies of the past and in LGBT+ culture of the present; it is very close to what drag queens portray. Roger Baker, in his study on drag and its historical counterparts in the theatre, describes how the pioneering drag queen entered the theatre scene at the end of the nineteenth century.[10]

Masquerade and carnival were popular forms of entertainment in the eighteenth century, at least in the phantasmic readings and uses of it in fin-de-siècle culture. Jean-Antoine Watteau, an important source of inspiration for Beardsley and Somov, often depicted characters from the commedia dell’arte, especially Pierrot. This topic stayed relevant in the times of decadence: Somov attended the Paris carnivals, where cross-dressing was a common practice; such events also took place in St. Petersburg, both at the fin de siècle and in the eighteenth century.[11] Catherine the Great organised masquerades with obligatory cross-dressing in eighteenth-century Russia.[12] Somov’s 1926 painting Masquerade from the cover of the German magazine Die Dame depicts such an event; in a 1925 version of the subject,[13] people dressed in contemporary clothing dance alongside those dressed in costumes inspired by the 18th century.

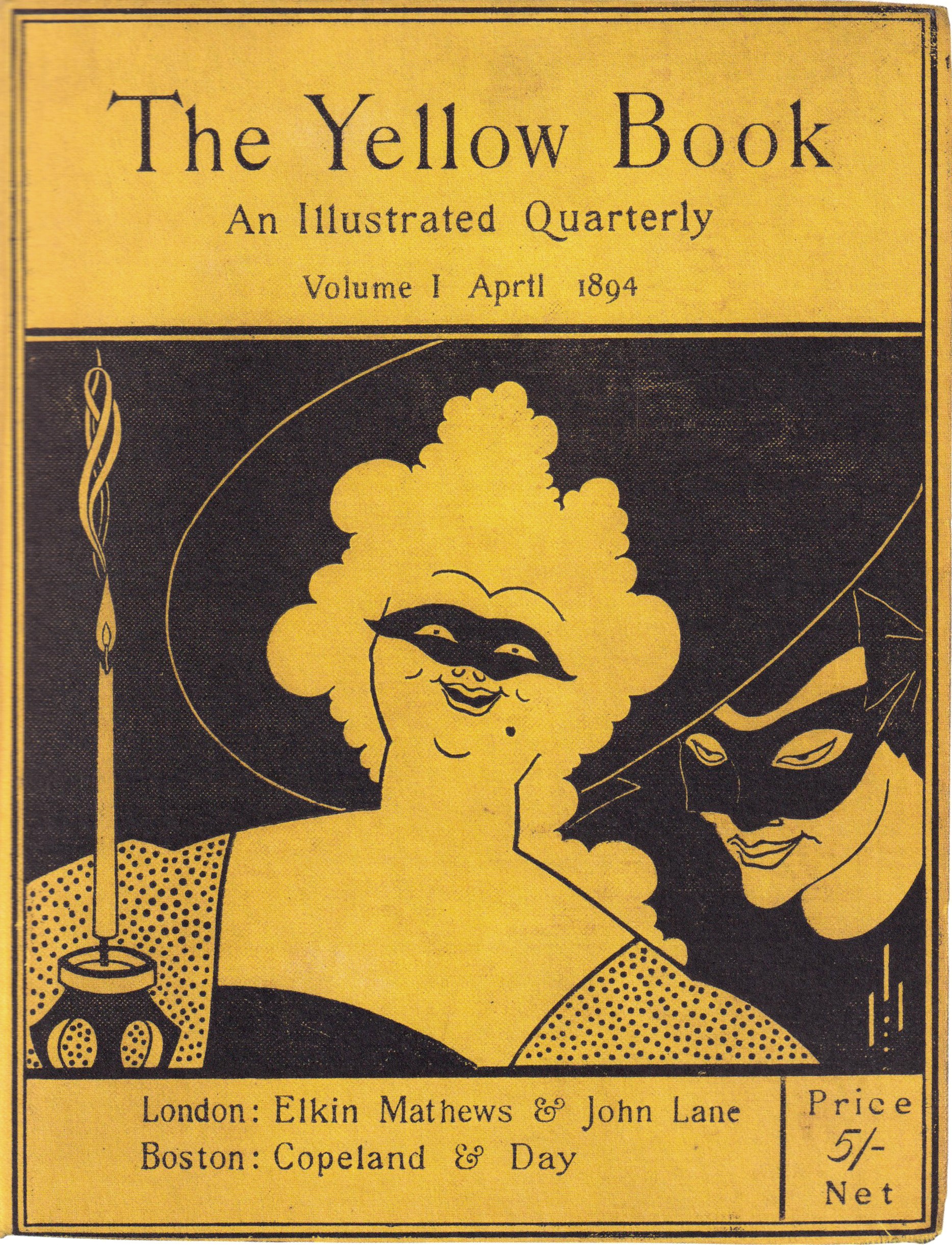

On the cover of the first volume of The Yellow Book, from April 1894, Beardsley depicts a smiling lady with a beauty patch, wearing a wig and a half mask, who closely resembles Somov’s ‘marquises’, with a sly figure behind her wearing a similar mask. She is reminiscent of one of Beardsley’s close friends, for whom the artist made a bookplate — Herbert Pollitt, who, as Diane de Rougy, performed on the stage of the Footlights Dramatic Club, at the University of Cambridge, the Serpentine Dance, becoming one of the prototypes of the modern drag queen. Lorraine Janzen Kooistra describes how cross-dressing was his and Beardsley’s shared interest, also acknowledging the queer and gender-bending nature of Salome in The Stomach Dance.[14]

The queer theme of masks, masquerades, and theatre, so common with both artists, brings to mind the concept of life as theatre and the idea of gender performativity. The masquerade, as Golubev notes, is an example of the difference between external and internal, a feeling which Somov confessed to having experienced.[15] This interpretation could be applied to one of Beardsley’s favourite subjects: a lady’s toilette, repeated in the illustrations to Salome, The Rape of the Lock, Under the Hill, La Dame aux Camélias. The artist depicts a woman’s creation/production/conception of herself, helped by other women and various ‘hermaphroditic’ Pierrot-like and dwarf-like creatures.[16] The theme of the toilette illustrates a behind-the-scenes moment which, in part due to the large mirrors and the overall monumentality of these scenes, turns each heroine into an actress preparing for her show, capturing the concept of femininity in quotation marks.

Both Beardsley and Somov portray Pierrot as an androgynous figure. It is noticeable in the case of Beardsley’s frontispiece for Pierrot of the Minute and of the Pierrot’s Library illustrations, in which Pierrot looks youthful and androgynous. Pierrot may be a personification of the artist himself.[17] In Somov’s watercolour Pierrot and the Lady, Pierrot is kissed by a lady wearing a half mask and a fluffy dress; both figures look ambiguously gendered, thus reminding of cross-dressing balls mentioned earlier.

Ewa Kuryluk notes that ‘men often turn into women in Beardsley’s drawings, and love scenes into lesbian scenes’.[18] Explicit sapphic imagery appears in Beardsley’s Lysistrata Haranguing the Athenian Women and Somov’s Tribades.

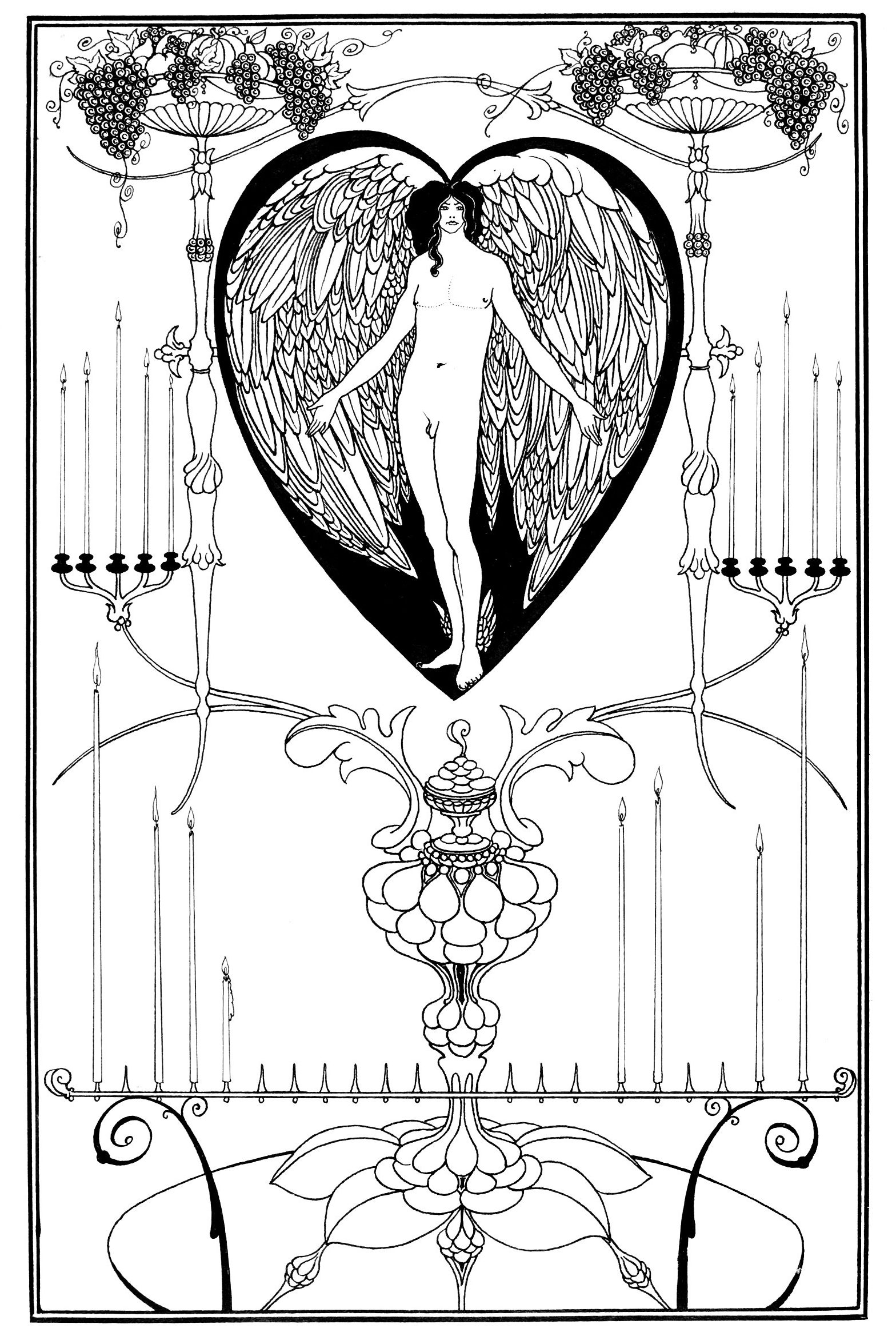

Another queer motif, of interest in decadent circles, was the figure of the Hermaphrodite, once worshipped by ancient Greeks, later revived in Romantic philosophy.[19] In 1895 drawing The Mirror of Love, Beardsley portrays a nude Hermaphrodite. It was conceived as a frontispiece for The Thread and the Path, a collection of poems by Mark André Raffalovich, the artist’s close friend who supported him financially at the end of his life. Raffalovich was the life partner of the poet and Catholic priest John Gray. It was he who encouraged Beardsley to convert to Catholicism a year before his death. Raffalovich was an author of the sexological treatise Uranisme et unisexualité, ‘uranism’ being a euphemism for homosexuality. Kuryluk points out that the mirror motif ‘invites the viewer to identify with [the Hermaphrodite]’ and that the symbol of the Hermaphrodite was important for queer contemporaries.[20] Taking into account all of the above, it can be said that this work was created for a queer audience from a point of view of and by a queer artist.

A special mode of subtextual communication, of associations and interpretations, was and is habitual for queer individuals and communities across the centuries. Aubrey Beardsley and Konstantin Somov were inevitably met with such recognition by like-minded people; of that, I shall provide two curious instances.

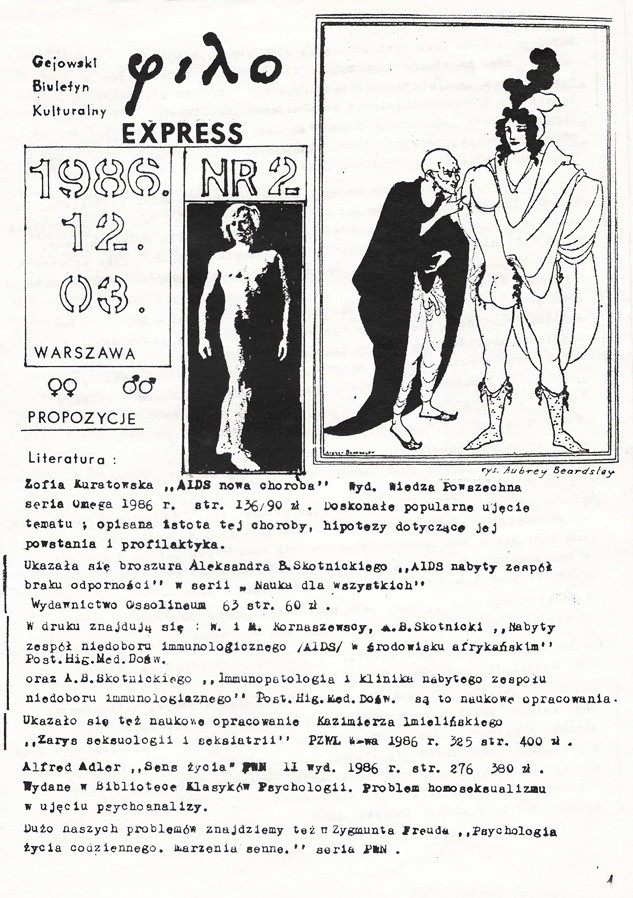

In 1986 and 1987, Beardsley’s Lysistrata illustrations appeared in Poland: they were reproduced in the first issues of the first Polish gay monthly magazine Filo, founded by gay rights activist Ryszard Kisiel. Thus, Beardsley received recognition from the then-emerging LGBT community almost a century later. This community believed his drawings to correspond to contemporary queer sensibility. The source from which chosen illustrations were reproduced was Ewa Kuryluk’s Salome albo o rozkoszy. O grotesce w twórczości Aubreya Beardsleya (Salome, or On Rapture. On the Grotesque in the Oeuvre of Aubrey Beardsley), published a decade earlier.[21] It became a cult book among Polish homosexuals from whom the author even received letters of gratitude, as she confessed in an interview to Karol Radziszewski and Wojciech Szymański (some of the objects from Kuryluk’s exhibition were displayed as part of Radziszewski’s research-based display ‘The Power of Secrets’ (‘Potęga Sekretów’, 2019, Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art).[22]

The reality of the Polish LGBT community at that time was quite similar to its Soviet counterpart’s — both endured censorship and discrimination. In 1969, the only exhibition of Somov’s art in the USSR had opened in Saint Petersburg, travelling to Moscow and Kyiv the following year. It deliberately avoided erotic drawings, an integral part of the artist’s oeuvre. Nevertheless, homosexual museum goers immediately recognised the queer quality of Somov’s art, despite the lack of factual evidence of his sexuality (neither the correspondence, nor the diaries, nor literature about it was yet published). Some excerpts about the portrait of Somov’s lover Mefodii Luk’ianov from a private letter to Petr Kornilov, Saint Petersburg art historian, read: ‘I was interested in a portrait of a certain Luk’ianov — an obvious snob and aesthete. Who is this Luk’ianov? He interests many’; ‘when I saw the portrait of Luk’ianov, I involuntarily felt something corrupt, but this does not prevent it from being intriguing’.[23]

The provocative nature of Beardsley’s and Somov’s art occasionally stood in the way of study and popularisation of their works, both during their lifetimes and long after their deaths. However, it simultaneously attracted like-minded people, boosting the artists’ status among the collectors and giving rise to a cult following. The admirers of their art were often queer and found a reflection of themselves in the erotic, theatrical, androgynous, camp, and grotesque imagery.

Notes

[1] Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, ‘Queer and Now’, in Tendencies (Durham & London: Duke University Press, 1994), pp. 1–20 (p. 8).

[2] Kathryn R. Kent, Making Girls into Women: American Women’s Writing and the Rise of Lesbian Identity (Durham & London: Duke University Press, 2003), p. 2.

[3] Angela Jones, ‘Introduction: Queer Utopias, Queer Futurity, and Potentiality in Quotidian Practice’, in Angela Jones (ed.), A Critical Inquiry into Queer Utopias (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), pp. 1–17.

[4] Ken R. Ireland, ‘Aspects of Cythera: Neo-Rococo at the Turn of the Century’, The Modern Language Review, 1975:70 (4), 721–30.

[5] Kuryluk, Ewa. 1976. Salome albo O rozkoszy: o grotesce w twórczości Aubreya Beardsleya (Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie), p. 112.

[6] Malcolm Easton, Aubrey and the Dying Lady: A Beardsley Riddle (London: Secker and Warburg, 1972), pp. 247–48.

[7] Pavel Golubev (ed.), Konstantin Somov: Dnevnik: 1917–1923 (Sankt-Peterburg: Dmitrii Sechin, 2017), p. 68.

[8] Golubev, Konstantin Somov: Dnevnik, pp. 68–69.

[9] Golubev, Konstantin Somov: Dnevnik, p. 69.

[10] Roger Baker, ‘Amateurs’, in Drag: A History of Female Impersonation in the Performing Arts (New York: New York University Press, 1994), pp. 144–57.

[11] Golubev, Konstantin Somov: Dnevnik, p. 71.

[12] Vera Proskurina, ‘Coup D’État as Cross-Dressing’, in Creating the Empress: Politics and Poetry in the Age of Catherine II (Brighton, MA: Academic Studies Press, 2011), pp. 13–48.

[13] The 1925 watercolour belongs in a private collection and has previously appeared at MacDougall’s and Sotheby’s auctions. See https://www.auction.fr/_fr/lot/somov-konstantin-1869-1939-masquerade-signed-and-dated-1925-8079953 (Accessed 19 February 2021).

[14] Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, ‘Sartorial Obsessions: Beardsley and Masquerade’, in William Evan Fredeman, David Latham (eds.), Haunted Texts: Studies in Pre-Raphaelitism in Honour of William E. Fredeman (Toronto–Buffalo–London: University of Toronto Press, 2003), pp. 178–83 (p. 182).

[15] Pavel Golubev, Konstantin Somov: Dama, snimaiushchaia masku (Moskva: Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie, 2019), pp. 20–21.

[16] John L. Duncan, Henry Maas, and Walter George Good (eds.), The Letters of Aubrey Beardsley (London: Cassell, 1970), p. 43.

[17] Fletcher, Ian. 1987. ‘A Grammar of Monsters: Beardsley’s Obsessive Images and Their Sources’, English Literature in Transition, 1880-1920, 30 (2), 141–63 (p. 153).

[18] Kuryluk, p. 71.

[19] Marion Praz, Mario, The Romantic Agony, trans. by Angus Davidson (New York: Meridian Books, 1956), p. 332.

[20] Kuryluk, p. 71.

[21] Lukasz Szulc, Transnational Homosexuals in Communist Poland: Cross-Border Flows in Gay and Lesbian Magazines (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), p. 173.

[22] Wojciech Szymański (email to the author, 12 September 2020).

[23] Golubev, Konstantin Somov: Dama, snimaiushchaia masku, p. 8–9.