On the 3rd of November 2020, the US President, Donald Trump, posted a message on Twitter as part of his campaign for re-election. The tweet simply comprised the words ‘VOTE! VOTE! VOTE!’ along with a link to a video.[1] Yet the video contained no message of policies or manifestos. Instead, it consisted entirely of footage of Trump himself, onstage at his rallies across the US, dancing and pumping his fists to ‘Y.M.C.A.’, the 70s disco hit by the Village People. In response, some journalists reached for the only term that made sense: camp. Matthew Walther, for example, coined the phrase ‘Trumpian camp’, and remarked on Trump’s exaggerated, incongruous appearance:

Everything about Trump as a physical specimen, from the skin (which is, in fact, orange) and the improbable hair and the pouting, curiously androgynous lips to the almost formless body, obese without seeming to possess actual flesh save for in the massive flanks (especially in golf or tennis shorts), is camp.[2]

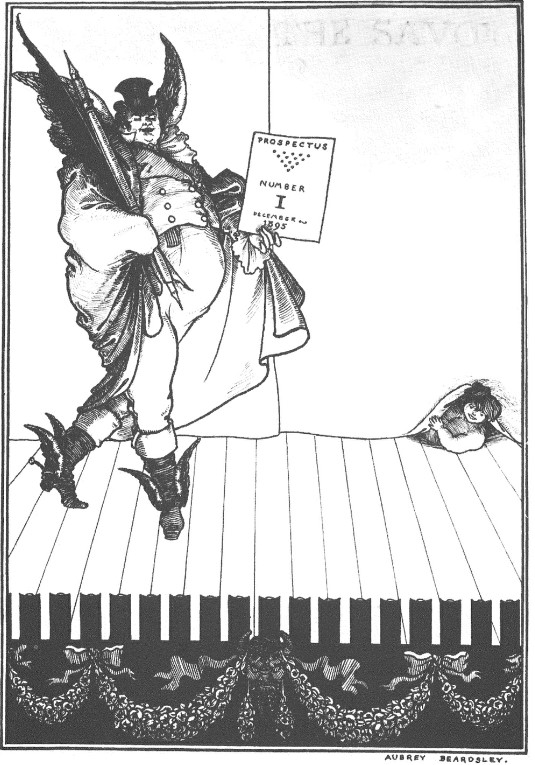

This description recalls the grotesque characters in many Aubrey Beardsley illustrations. In fact, when revisiting the John Bull figure that Beardsley proposed for the prospectus to the Savoy magazine, issue no. 1 (1895), it is difficult not to notice the resemblance to Trump: all grotesque bulk, power, and dainty hands.

Walther’s article, like several discussions on the camp of Trump, uses definitions from Susan Sontag’s 1964 essay ‘Notes on “Camp”’, whose ‘canon of Camp’ includes the drawings of Beardsley.[3] Indeed, these Trumpian definitions equally apply to the work of Beardsley. For Walther, Trumpian camp is Sontag’s ‘love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration’.[4] For Donna M. Goldstein and Kira Hall, it ‘incarnates a victory of “aesthetics” over “morality”, representing ‘a variant of sophistication, but hardly identical with it’.[5] For Alex Symons, it represents a certain ‘spirit of extravagance’ that ‘cannot be taken altogether seriously’.[6] If a contemporary figure like Trump demands to be described as camp in this way, it is useful to examine a little of the history of the term: a history that includes Beardsley from as early as the 1920s.

The earliest known use of ‘camp’ in a piece of literary criticism appears in a 1922 article on the novelist Ronald Firbank. Writing in the New Orleans modernist magazine The Double-Dealer, Carl Van Vechten was faced with the task of describing Firbank’s style, which is so elliptical that one chapter of a Firbank novel, Inclinations (1916), comprises the following line of dialogue alone:

Mabel! Mabel! Mabel! Mabel!

Mabel! Mabel! Mabel! Mabel![7]

Van Vechten offered an effusive string of similes: Firbank was like ‘a Uranian version of Alice in Wonderland’, ‘“A Rebours” à la mode’, ‘Jean Cocteau at the Savoy’, and ‘Aubrey Beardsley in a Rolls-Royce’.[8] In the same paragraph, he described Firbank’s dialogue: ‘In the argot of perversity, one would call it camping’.[9] By ‘the argot of perversity’, Van Vechten meant homosexual slang.

The first attempt to properly define the term in print was in 1909, in a knowing dictionary of Victorian slang by James Redding Ware. Camp, Ware wrote, meant ‘actions and gestures of exaggerated emphasis’.[10] A more explicitly homosexual definition appeared the following year, in an article by I. L. Pavia, published in the sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld’s journal, Jahrbuch für sexuelle Zwischenstufen (Yearbook of Sexual Intermediaries). Titled ‘Male Homosexuality in England with Special Consideration of London’, Pavia’s article featured a section on homosexual slang, in which ‘camp’ was defined as ‘homosexuell im Sinne des typisch-weibischen, exzentrischen Homosexuellen’ (‘homosexual in the sense of a typically effeminate, exaggerated Homosexual’).[11] Ware’s and Pavia’s separate definitions prove that the term ‘camp’ was in circulation as homosexual slang by 1910, and that the key defining adjective for the term was ‘exaggerated’, which certainly applies to the styles of Beardsley.

Victorian though the term ‘camp’ was, its nineteenth-century usage was confined to small circles of homosexual sex workers, along with their friends and clients. If Oscar Wilde and Aubrey Beardsley were aware of the word, they kept it out of their letters. Even Van Vechten’s usage in 1922 was too obscure for Firbank, as it would have been to many readers. In an unpublished letter, the homosexual Firbank asked Van Vechten: ‘What does “camping” mean?’[12] Significantly, when Van Vechten revised his Firbank article for book form, he excised the ‘camping’ line.[13] But another comparison, ‘Aubrey Beardsley in a Rolls-Royce’, suited Firbank so much that his publisher Grant Richards used it to publicise Firbank’s books in the Times Literary Supplement.[14] The Beardsley line has been quoted when describing Firbank’s fiction ever since, including in Angela Carter’s radio play about Firbank, A Self-Made Man (1984).[15]

Firbank was an avid collector of Beardsley, and in 1914 even pitched his first proper novel Vainglory (1915) to Richards as a continuation of Beardsley’s project. As Firbank discovered with delight, Richards had socialised with Aubrey Beardsley as a young man, and had visited him regularly at his home in Cambridge Street, Pimlico.[16] Richards recalled how this connection figured in Firbank’s pitch:

He [Firbank] had attempted to do something [in prose] like Aubrey Beardsley had done in the illustrations to The Rape of the Lock. Was I an admirer of Beardsley? […] So I knew Beardsley…! Surely I would bring his child into the world. I could not be so unkind as to turn it from my door.[17]

The comparisons continued after Firbank’s death in 1926, hinting at the way Beardsley had become a synonym for a camp literary style. In 1929, Evelyn Waugh praised Firbank while admitting he ‘owes something to Under the Hill’ without naming its author: a reference that shows how well-known Beardsley’s prose work was at that time.[18] By 1949, Beardsley’s prose had become much less known than his art, as indicated in Jocelyn Brooke’s fictionalised memoir A Mine of Serpents, in which a camp character remarks: ‘You haven’t read Firbank? Oh my dear you must – Beardsley in prose, but much better’.[19]

The explicit use of the term ‘camp’ in discussions of Beardsley emerges during what Gary McMahon calls the ‘camp renaissance’ of the 1960s, following Sontag’s ‘Notes on “Camp”’.[20] Though camp had existed in art and literature since the 1890s, Sontag’s essay showed that the 1960s was the time to properly articulate this sensibility. As Brigid Brophy observed, the landmark V&A exhibition on Beardsley in 1966 coincided with the era of Swinging London, when sexual liberation – not least regarding changes to the laws on homosexuality – found a mirror in Beardsley’s ‘polymorphous perversity’.[21] ‘Beardsley’, she noted at the time, ‘highest of high Catholic camp […] has been carried shoulder-high, on the pretty, bacchanal rout of current camp-followers, into his kingdom, the transvestitely dandified realm of Carnaby Street’.[22] Kate Hext names specific boutiques, noting how ‘the naughty-campiness of Aubrey Beardsley reappeared [in the 1960s] through the clothing designs of Antony Little for Biba, and John Pearce for Nigel Waymouth at Granny Takes a Trip.’[23] In the film Carry On Loving (1970), Beardsley prints are used in this way as part of the décor of a fashionable London flat. The scene therefore juxtaposes two types of camp at once: the 1890s ‘high’ camp art of Beardsley prints, alongside the ‘low’ camp comedy of the bawdy Carry On scripts.

Brophy’s 1968 monograph on Beardsley provides an example of his campness in prose. One particular passage in Under the Hill reads as ‘very pretty, camp and Firbankian’.[24] It is steeped in the blend of irreverence, affection, and innuendo that is so common in camp:

[He thought] Of Saint Rose, the well-known Peruvian virgin; […] how she was beloved by Mary, who, from the pale fresco in the Church of Saint Dominic, would stretch out her arms to embrace her; […] how she promised to marry Ferdinand de Flores, and on the bridal morning perfumed herself and painted her lips, and put on her wedding frock, and decked her hair with roses, and went up to a little hill not far without the walls of Lima; how she knelt there some moments calling tenderly upon Our Lady’s name, and how Saint Mary descended and kissed Rose upon the forehead and carried her swiftly into heaven.[25]

Brophy also detects camp innuendo in the accompanying illustration by Beardsley, The Ascension of Saint Rose of Lima (1896). Rose and Mary are depicted floating in an embrace against a rural landscape: for Brophy this is clearly ‘the bliss of gratified lesbianism’.[26]

Furthermore, anticipating the internet’s slash fiction genre, Brophy cannot resist imagining the figures as the sisters of Beardsley and Firbank: ‘I can find no evidence they so much as met; but if poetic justice exists, surely Mabel Beardsley had a love affair with Heather Firbank’.[27] It is no wonder that Brophy also finds room for a Beardsley reference in her camp experimental novel In Transit (1969), which is full of gender play and Joycean puns. In one scene, a revolution breaks out in an airport lounge, during which someone scrawls a graffito on a wall that has elements of a Carry On line: ‘DON’T FORCIBLY SHAVE ME, NURSE – I’M TRYING TO GROW A BEARDSLEY’.[28]

Subsequent studies of camp have continued to acknowledge Beardsley as a key example. Gary McMahon’s Camp in Literature (2006) calls Under the Hill ‘the most camp writing in the canon’.[29] Mark Booth’s Camp (1983) uses a caricature of Beardsley in its title page, and refers to Beardsley’s art as something ‘we can call camp with total confidence’.[30] Booth focuses on the use of ‘prodigious vanity’ as ‘the most vaunted feature of camp performance’, citing an example in Under the Hill which now anticipates the vanity of Donald Trump’s tweets:

[He] slipped off his dainty night-dress, posturing elegantly before a long mirror, and made much of himself. Now he would bend forward, now lie upon the floor, now stand upright, and now rest upon one leg and let the other hang loosely till he looked as if he might have been drawn by some early Italian master.[31]

In the shadow of a pandemic, it is pertinent to consider camp’s history as a strategy of self-care. Consider, for example, the defiance of Trump’s dancing at his rallies following his struggle with Covid-19, despite the likelihood (now proven) of his failure in the polls. Similarly, as Philip Core puts it in his entry on Beardsley in Camp: The Lie that tells the Truth (1984), the buoyancy with which Beardsley faced his own respiratory illness derived ‘entirely from his inner strength, which manifests the vigorous and joyous deception of confident camp’.[32] Camp can be what the queer theorist Eve Sedgwick calls a ‘reparative practice’, offering a kind of ‘plenitude’ of ‘resources to offer to an inchoate self’.[33] The pleasure people continue to take from Beardsley’s work owes something to this very quality: in its excess and exaggeration not merely entertaining, but sustaining.

Notes

[1] Joe Middleton, ‘2020 Election: Donald Trump Dances to YMCA in Final Campaign Video’, Independent (UK), 3 November 2020. Tweet posted by Donald Trump, 3 Nov 2020, currently withheld by Twitter ‘in response to a report from the copyright holder’ [accessed 31 December 2020].

[2] Matthew Walther, ‘How Camp Explains Trump’, The Week (US), 30 November 2020.

[3] Susan Sontag, ‘Notes on “Camp”’ (1964), in Sontag, Against Interpretation and Other Essays (1966; repr. London: Penguin, 2009), pp. 275-92 (p. 277).

[4] Walther, ‘How Camp Explains Trump’. Sontag, p. 275.

[5] Donna M. Goldstein and Kira Hall, ‘Postelection surrealism and Nostalgic Racism in the Hands of Donald Trump’, Hau: Journal of Ethnographic Theory, 7.1 (2017), 397-406 (p. 401). Sontag, pp. 287, 275.

[6] Alex Symons, ‘Trump and Satire: America’s Carnivalesque President and His War on Television Comedians’, in Trump’s Media War, ed. by Catherine Happer, Andrew Hoskins, and William Merrin (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), pp. 183-97 (p. 191). Sontag, pp. 283, 284.

[7] Ronald Firbank, Inclinations (1916), in Firbank, ‘Vainglory’ with ‘Inclinations’ and ‘Caprice’, ed. by Richard Canning (London: Penguin, 2012), pp. 179-293 (p. 256).

[8] Carl Van Vechten, ‘Ronald Firbank’, The Double Dealer, 3.16 (April 1922), 185-6 (p. 186).

[9] Van Vechten, ‘Ronald Firbank’ (1922), p.186.

[10] James Redding Ware, Passing English of the Victorian Era: A Dictionary of Heterodox English, Slang, and Phrase (London: George Routledge, 1909), p. 61.

[11] I. L. (Leo) Pavia, ‘Die männliche Homosexualität in England mit besonderer Berücksichtigung Londons’, Jahrbuch für sexuelle Zwischenstufen, 11 (1910), 18-51 (p. 40).

[12] Ronald Firbank, letter to Carl Van Vechten, 4 May 1922, Berg Collection, New York Public Library, ref: BERG COLL MSS FIRBANK. Kate Hext, ‘Rethinking the Origins of Camp: The Queer Correspondence of Carl Van Vechten and Ronald Firbank’, Modernism/modernity, 27.1 (January 2020), 165-183 (p. 169).

[13] Carl Van Vechten, ‘Ronald Firbank’, revised version, in Van Vechten, Excavations: A Book of Advocacies (New York: Knopf, 1926), pp. 170-76.

[14] Grant Richards, ‘Grant Richards Ltd’, advertisement, Times Literary Supplement, 18 May 1922, p. 322.

[15] Angela Carter, A Self-Made Man, script for radio play (first broadcast 1984), in Carter, The Curious Room: Plays, Film Scripts and an Opera, ed. by Mark Bell (London: Chatto & Windus, 1996), pp. 121-51 (p. 146).

[16] Grant Richards, Memories of a Misspent Youth, 1872-1896 (London: William Heinemann, 1932), p. 274

[17] Grant Richards, Author Hunting: By An Old Literary Sportsman – Memories of Years Spent Mainly in Publishing, 1897-1925 (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1934), p. 249.

[18] Evelyn Waugh, ‘Ronald Firbank’, in Waugh, A Little Order: Selected Journalism, ed. by Donat Gallagher (1977; repr. London: Penguin, 2019), pp. 77-80 (first publ. in Life and Letters, 2.10 (March 1929), 191-96), p. 77.

[19] Jocelyn Brooke, A Mine of Serpents (London: Bodley Head, 1949), p. 126.

[20] Gary McMahon, Camp in Literature, (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2006), p. 5.

[21] Brophy, Black and White, p. 68.

[22] Brophy, Black and White, p. 68.

[23] Hext, p. 180.

[24] Brophy, Black and White, p. 24.

[25] Aubrey Beardsley, Under the Hill (1896), in Beardsley, In Black and White: The Literary Remains of Aubrey Beardsley, ed. by Stephen Calloway and David Colvin (London: Cypher, 1998), pp. 1-114 (pp. 72-76).

[26] Brophy, Black and White, pp. 24-26.

[27] Brophy, Black and White, p. 26.

[28] Brophy, In Transit: An Heroi-Cyclic Novel (1969; repr. Chicago, IL: Dalkey Archive, 2002), p. 209.

[29] McMahon, p. 9.

[30] Mark Booth, Camp (London: Quartet, 1983), pp. 5, 50.

[31] Booth, p. 90. Beardsley, Under the Hill, p. 82.

[32] Philip Core, Camp: The Lie That Tells The Truth (London: Plexus, 1984), p. 28.

[33] Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003), pp. 149-50.