Since the Coronavirus pandemic crisis tightened its grip on economies, freedom of movement and social interaction, the home has been on our agenda more than ever. For some, isolation and the sudden increase of spare time has led to redecorating, cleaning, and gardening; for others, working from home has necessitated the reconfiguration of living spaces to accommodate professional needs. When quarantine stopped physical gathering, our impulses as social beings found expression on social media; need for work meetings has been translated into the ‘Zoom room’. Suddenly the home is the setting for all types of interaction, transformed into a stage where people curate their living space for all to see and perform their job via a carefully orchestrated mise-en-scene: backgrounds of magnificent book collections are filmed by webcams strategically placed so hoovers and piles of washing are just out of shot.

This self-fashioning through the home is of course not a new phenomenon, but at this time it is interesting to consider a figure from a different century whose home was similarly a place of self-isolation due to poor health, a place of work, and a place through which he built his identity. Aubrey Beardsley’s nomadic life, cut tragically short at the age of 25 by tuberculosis, perhaps makes him a surprising figure to look at in relation to notions of home. However, at the height of his short career, his house became intrinsic to the promotion of his artistic persona and served as the inspiration for a number of his drawings. Following the regrettable early closure of the Aubrey Beardsley exhibition at Tate Britain, I hope this article may bring some of the delights of Beardsley into your own home.

114 Cambridge Street

After a childhood punctuated by frequent moves of home, June 1893 marked a happy time for Beardsley when his growing reputation, numerous artistic commissions, and brighter financial prospects enabled the family to move to 114 Cambridge Street, in ‘genteel, if hardly fashionable Pimlico’ in London.[1] Beardsley and his sister, Mabel, quickly set about transforming the rooms of this property with remarkable decoration, hiring Beardsley’s friend the designer and writer on art Aymer Vallance to do it. His design included black lacquered woodwork and orange walls to resemble the famous house of Des Esseintes in the novel A Rebours (1884) by Joris-Karl Huysmans, a book which came to be ‘the Bible and bedside book’ and ‘the breviary of the Decadence’ for its celebration of deliberate artificiality and hyper aesthetic sensibility.[2] This extraordinary scheme of domestic decoration played a vital role in shaping for Beardsley the unique artistic persona that we know today.

At a time when the ‘home interview’ became a popular journalistic device, Beardsley’s choice of interior décor can be understood as a self-conscious manipulation of his public image, giving us great insight into the mind of the artist.[3] From this highly complex and personal space, many of Beardsley’s artistic ventures began. The decoration of his rooms provided the atmosphere and inspiration needed for producing many of his drawings, where the fabric of his surroundings was translated onto the surface of his work. Beardsley’s time at 114 Cambridge Street was tragically short-lived due to the loss of income as a result of his unfortunate association with the Oscar Wilde scandal. However, this makes the 114 Cambridge Street period particularly significant as the only period of Beardsley’s life when he enjoyed, as Stephen Calloway observes, a degree of prosperity and relative financial security, lived comfortably, bought furniture, books and prints, expressed his tastes through interior decoration, and entertained.[4]

Violent Orange: Inspiration by Candlelight

Beardsley’s striking home decoration quickly made 114 Cambridge Street famous. Mabel Beardsley’s friend and colleague, the author Netta Syrett recalled the drawing room ‘with its deep orange walls, black doors, and black painted book-cases and fireplaces’, which she proclaimed was ‘a scheme of colour new to me’.[5] Beardsley’s friend, the painter William Rothenstein, wrote that ‘the walls were distempered a violent orange, the doors and skirtings were painted black; a strange taste […] but his taste was all for the bizarre and exotic’.[6] Historic paint consultant Patrick Baty suggests the colour could have been chrome orange or red lead (personal communication). As noted above, by choosing orange, Beardsley aligned himself with Huysmans’s decadent character from A Rebours, Des Esseintes, who ‘desired colors whose expressiveness would be displayed in the artificial light of lamps […] for it was at night that he lived’.[7] Beardsley likewise preferred the artificial light of his candles, which often struck visitors such as Syrett who noted how, ‘the room was always rather dark, for it was an affectation of the Beardsley set to exclude the “crude light of day”’.[8] This quote echoes Huysmans’s description of how some colours look ‘lifeless or crude in daylight’.[9] It seems unsurprising that Beardsley habitually laboured late into the night by candle light.[10]

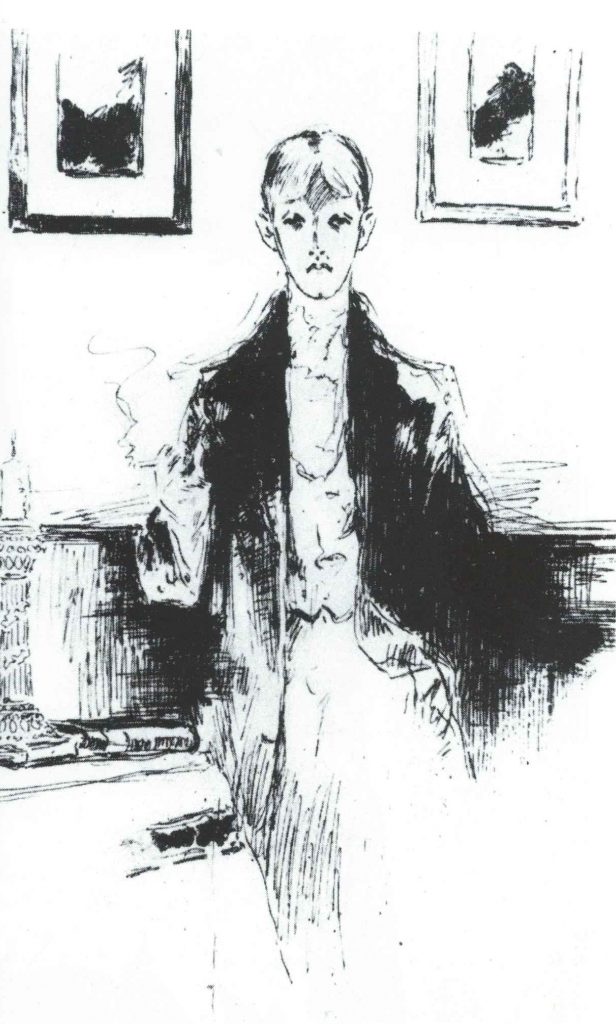

Beardsley and Mabel painted their low-budget furniture black to introduce a unifying scheme, including the desk at which Beardsley sat to draw. On it rested his treasured ‘massive gilt French Empire’ candlesticks that followed him from home to home and on his travels to France.[11] One of them can be seen in Penrhyn Stanlaws’s sketch for his interview, ‘Some Personal Recollections of Aubrey Beardsley’. It is tempting to imagine that, as Beardsley paused to think while working at his desk, he would have stared into the flames of these candles and the grotesque globules created by their dripping wax, and perhaps would have been intrigued by their quasi-natural forms animated by the flickering light.

Foetuses are a recurring motif throughout Beardsley’s oeuvre. They can be considered to link the key themes of Beardsley’s work: shocking depictions of sexuality, life and death. It is possible that the bulbous growths of hot wax dripping down the candles on his work table may, at least in part, have been an inspiration for these motifs.

In 1893, J. M. Dent and Company published Bon-Mots illustrated with ‘grotesques’ by Beardsley (so described in the frontispiece). The vignette on page 26 of the Bon-Mots of Sydney Smith and Richard Brinsley and page 123 in the Bon-Mots of Charles Lamb and Douglas Jerrold was published while Beardsley lived at 114 Cambridge Street. It depicts a foetus placed between the hands of what might be a weary mother and an old abortionist. The foetus is juxtaposed with the lit candle in the middle of the scene and appears as if it might itself be an accumulation of dripping wax down its sides. The flame of the candle mirrors the feather in the hat of the mother and this association perhaps indicates her as the life-giver of the foetus in the same way that the candle animates and produces the congealed drips of wax. The sunflower petals around the mother’s collar, however, align her with Aestheticism and Decadence. In the early 1890s, the Decadent aesthetic was described as ‘a new and beautiful and interesting disease’.[12] This association, and the violence of the flame, creates an uncomfortable edge, compounded by the dazed, half-closed eyes of the mother, the greedy look in the eye of the ambiguously gendered putative abortionist and the knife handle sticking out of his/her coat pocket.

The grotesque nature of the vignette is generated by uncomfortable juxtapositions, between the natural and unnatural, young and old, life and death, and beauty and illness. The sinister scene seems to emanate from the candle, almost as though it could be Beardsley’s imaginary extension of what he saw as he stared at the candles in the dark room. Through this illustration, we can get a sense of the artistic importance of Beardsley’s interiors, where the décor of his real-life surroundings bled into the interior worlds of his artworks.

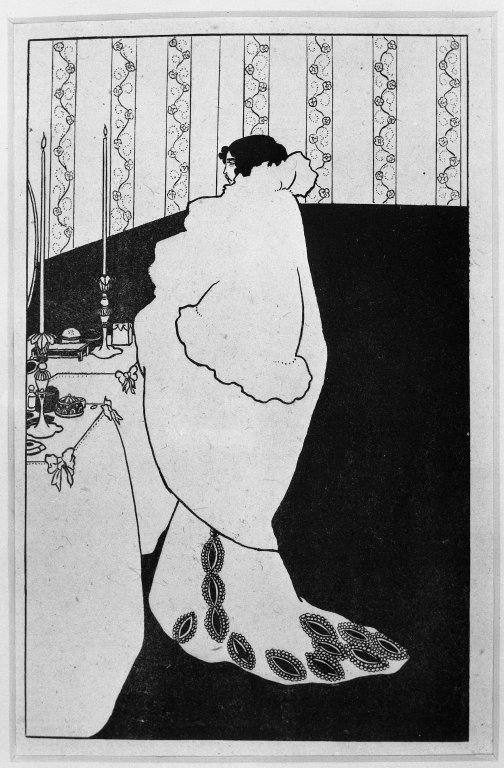

Incorporating the design of his rooms into his illustrations was not unusual for Beardsley. The art critic Haldane MacFall described his wallpaper as ‘stripes running from ceiling to floor in the manner he so much affects for the designs of his interiors, such as the famous drawing of the lady standing at her dressing table, known as La Dame aux Camélias’.[13] However, the signature mark in Beardsley’s ‘grotesque’ for Bon Mots perhaps most explicitly illustrates how the fabric of Beardsley’s interiors were translated into his artistic identity. Here, the stout candle, wax and foetus of the illustration are paralleled in Beardsley’s unusually thick signature on the left-hand side. Positioned like three candles in a candelabra, the tops slant like that of the partly melted candle in the centre. Three drips fall from the middle of Beardsley’s signature resembling drips of wax. The feather of the woman’s jet-black hat while mirroring the flame of the candle, is positioned above Beardsley’s thick black signature, as though providing a flame to the stylised candles. Here the fabric of the interior can be regarded as inspiration for the device with which Beardsley signed his drawings.

A Place to Pose: The Home as Public Platform

Beardsley used his home at 114 Cambridge Street as a stage on which he promoted himself and his art. He and Mabel frequently held tea parties on Thursday afternoons where he would pose as a gentleman among his books. These occasions were an opportunity for Beardsley to show his latest works, which were often on display and passed around for comment.[14]

Beardsley utilised the surfaces of his interiors to construct his Decadent personality. Through curating immaculate clothes, finished prints, and exotic plants sprayed with perfume, he presented himself as a decadent artist in pursuit of heightened sensory experience. On one occasion, the day before hosting a party, Beardsley wrote to the writer Ada Leverson, asking if she would come ‘an hour earlier than the others’ to help him ‘scent the flowers.’ Upon arrival, she discovered he was serious and was spraying bowls of gardenias and tuberoses with opoponax. He handed her a spray of frangipani for the Stephanotis.[15]

Jane Desmarais has observed that while Beardsley was frequently housebound due to his tuberculosis, the expanding periodical press provided opportunities for exposure, making it possible for him to shape his public image through his interiors. The ‘home interview’ genre used descriptions of the interviewees’ homes as an ‘index’ of their character, meaning domestic interiors could be used as a tool for self-promotion on a large scale.[16] Beardsley was interviewed seven times between 1893 and 1897; during this time, he is reported to have mentioned that ‘interviewing [was] a wonderful and terrible business’. Wanting fame, Beardsley saw all publicity, both good and bad, as desirable.[17]

Accordingly, he sought to shock visitors by hanging on his walls the Japanese erotic prints that he found inspirational, such as one by Kitagawa Utamaro from a book given Beardsley by Rothenstein. Visiting artists’ homes in preparation for writing Modern Art (1908), art historian Julius Meier-Graefe took a trip to Beardsley’s home in Cambridge Street. On seeing Beardsley’s Japanese prints from a distance, he believed them ‘delicate’ and ‘decent’ but on drawing nearer was shocked to discover their true nature. He was so struck by these that he began his chapter on Beardsley by discussing them, as it seemed to him so expressive of a modern and unconventional sensibility.[18]

The interiors of 114 Cambridge Street were intrinsically linked with Beardsley’s artistic voice and identity. The rooms of this property helped Beardsley to construct his celebrated persona, both in the public eye and amongst his friends. Although today most of us have not yet gone to the lengths of Beardsley to be noticed with our choices of backdrops to our own ‘home interviews’, the influx of home sharing on social media has revealed a curation of perhaps a more subtle, discreet and unspoken nature. Domestic interiors are often performative extensions of the self, and are perhaps even more so in this time of coronavirus. Like Beardsley’s, our homes have become a space where the personal, the public, and the realms of leisure and work have come to reside.

[1] Stephen Calloway, Aubrey Beardsley (London: V & A Publications, 1998), p. 86.

[2] Calloway p.91. Quoted by Stanley Weintraub, Aubrey Beardsley: Imp of the Perverse (London: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1976), p. 23.

[3] See Jane Haville Desmarais, The Beardsley Industry: The Critical Reception in England and France 1893 to 1914 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1998), pp.29-31.

[4] Calloway, p. 84. Also see letter from Beardsley to A. W. King, 27 September 1893: ‘For the moment I have fortune at my foot, but I can tell [you] I have worked hard for it’. Aubrey Beardsley, The Letters of Aubrey Beardsley, ed. by Henry Maas, J. L. Duncan, and W. G. Good (London: Cassell, 1970), p. 55.

[5] Netta Syrett, The Sheltering Tree (London: Geoffrey Bles, 1939), p. 78.

[6] William Rothenstein, Men and Memories: Recollections of William Rothenstein, 1872-1900, 2 vols (London: Faber and Faber, 1931), i, p. 134.

[7] J.-K. Huysmans, Against the Grain (New York: Lieber & Lewis, 1922), p. 33.

[8] Quoted in Calloway, p. 98.

[9] Huysmans, p. 33.

[10] Weintraub, p. 22.

[11] Calloway, pp. 96-7.

[12] Arthur Symons, ‘The Decadent Movement in Literature’, Harper’s Magazine, November 1893, pp. 858–67 (p. 859).

[13] Quoted in Calloway, p. 92.

[14] Calloway, pp. 86-87.

[15] Osbert Sitwell, Noble Essences: A Book of Characters (Boston: Little, Brown & Co, 1950), p. 154.

[16] Desmarais, pp. 29–31.

[17] Desmarais, p. 31.

[18] See Calloway, pp. 98–99; Julius Meier-Graefe, Modern Art: Being a Contribution to a New System of Aesthetics (London: Heinemann, 1908), p. 252.