If people remember anything about the friendship between Aubrey Beardsley and William Rothenstein, it’s probably the story Rothenstein tells in his memoirs about a certain stash of erotic Japanese prints. Rothenstein had picked up the prints in Paris in the form of a book, possibly Utamaro’s famous 1788 Utamakura (Poem of the Pillow), but found the pictures, in his own words, ‘so outrageous that its possession was an embarrassment’. He passed them onto Beardsley, who removed ‘the most indecent prints from the book and hung them around his bedroom’.[1] As if this wasn’t enough, Rothenstein noted that Beardsley shared the house (114 Cambridge Street in Pimlico) with his mother and sister.

The story plays up to the assumed personalities of both: Rothenstein, open to a wide range of stimuli, but a little earnest at heart; Beardsley, gloriously, unashamedly open.[2] It speaks to other aspects of Rothenstein’s personality also, chiefly his ability to influence his contemporaries, not necessarily through his own art or ideas, but by putting them in contact with the ideas and art of others. He was above all one of the great facilitators of the period.

Beardsley and Rothenstein were born in the same year, and first met in Paris in May 1893, shortly after Beardsley’s dramatic debut in The Studio magazine. They were both barely twenty, but equally precocious. The Bradford-born Rothenstein had already met many of the key players in the Parisian art scene by this time – including Edgar Degas, Henri Toulouse-Lautrec, and Puvis de Chavannes – and was about to settle in London, where he was eager to make an impact. Beardsley was similarly primed for artistic notoriety.

Encouraged by their initial meeting (during which Rothenstein recalled Beardsley being ‘interested in my paintings’), the two artists continued their friendship in London, even working together for a while in Beardsley’s studio. Rothenstein had a literal front-row seat when Beardsley embarked on his Salome drawings. They also collaborated on a nautically-themed dialogue – a few pages of which have survived – and shared their enthusiasms for a wide range of subjects, from Japanese prints to Balzac.[3] For the next few years they moved in similar social circles (which included fellow artists such as Charles Conder and Max Beerbohm) and spaces (from the Café Royal to Dieppe) and were involved in many of the same ventures: Rothenstein wrote two short articles for The Studio in 1893 (nos 2 and 4), while both would go on, of course, to feature in The Yellow Book and The Savoy. Rothenstein continued to be associated, and in close contact, with Beardsley until the latter’s death in 1898.

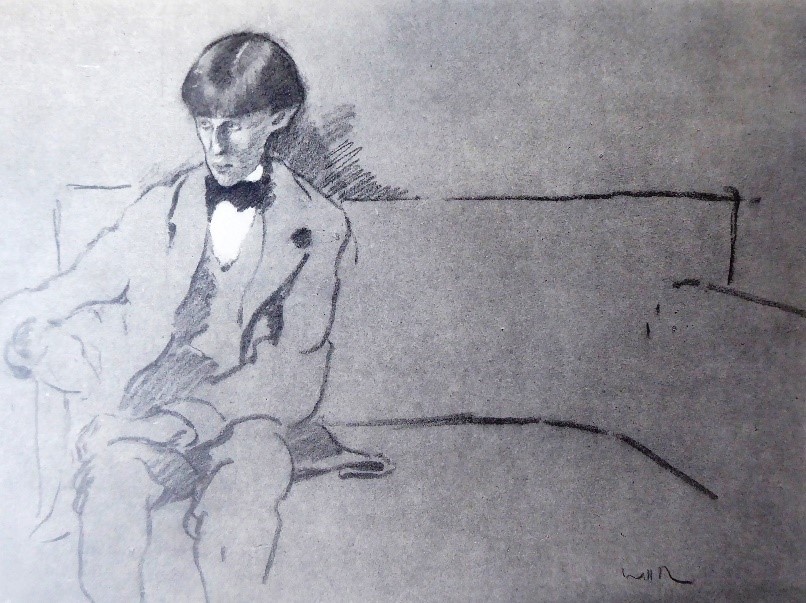

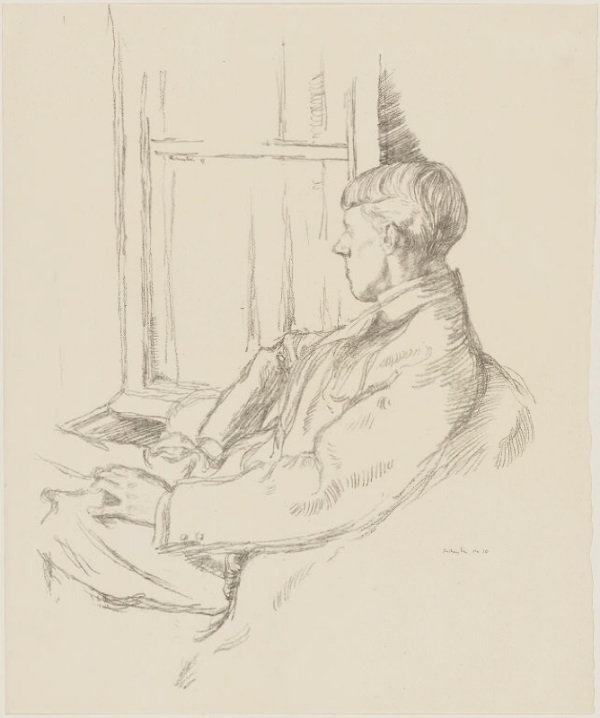

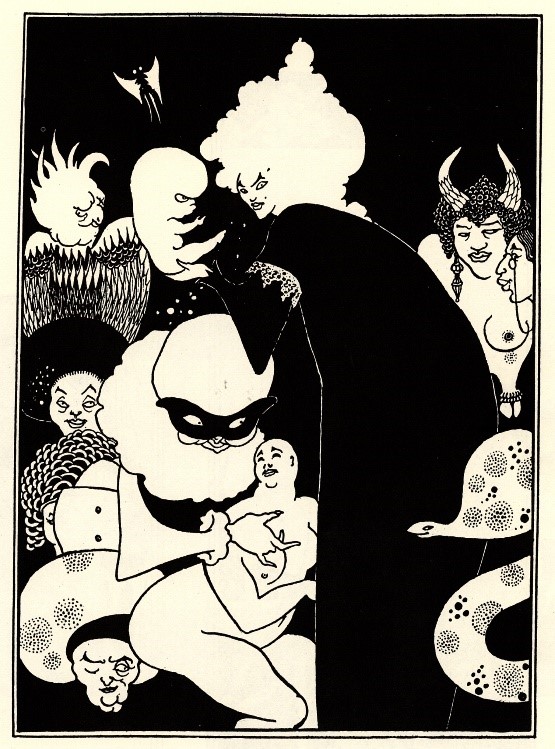

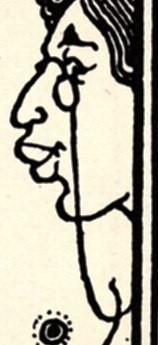

Mutual portraits would inevitably follow. Rothenstein drew Beardsley twice in 1893, seated at one end of a plain sofa, peering out from under his famous fringe. Rothenstein would return to Beardsley in a lithographic portrait of 1897; seen, this time, from behind, staring pensively into the mid distance again. Beardsley left no official portrait of Rothenstein, but it is generally accepted that he appears on the far right of the 1893 drawing Lucian’s Strange Creatures, made during the first flush of their friendship.

The difference in style between these portraits suggests that, artistically, they were not following parallel paths, and to some extent this is true. Rothenstein’s portraits of the 1890s are sensitive, impressionistic affairs, with largely broken outlines. Beardsley is bolder and brasher: no bets hedged. Curiously, though, while Rothenstein’s Beardsley looks a little nervous, Beardsley’s Rothenstein (whose head appears above a typically prominent nipple) is full of confident mischief. It’s very possible that roles were sometimes reversed: Beardsley, after all, was not incapable of being severe, nor Rothenstein audacious.

It could be argued that the artistic connections between the two artists should be sought not in explicit visual similarities, but in their general approach. There are many possible points of departure here, including the two artists’ shared love of particular ‘old masters’ such as Mantegna, or contemporary caricature. In 1895 Rothenstein travelled to Spain to see, and write about, Goya (a series of ‘Spanish’ paintings would follow).[4] Beardsley seems to have remained tight-lipped regarding the possible influence of Goya on his own practice – but it’s hard to imagine that Goya never came up in conversations between the two.

The most interesting connection, though, lies in the fact that they both drew heavily on literature. Rothenstein was never, strictly speaking, an illustrator – although he did begin work on a series of illustrations after Voltaire, one of which appeared in The Savoy in 1896. However literature – including Balzac, Ibsen, and Browning – was the inspiration for several paintings he produced during the mid- to late 1890s (see, for instance, Parting at Morning, 1891; Porphyria (or Porphyria’s Lover), 1894; Le Grand-I-Vert, 1899; The Doll’s House, 1899; and The Browning Readers, 1900).

Like Beardsley, whose ‘illustrations’ represent a carefree and often bewildering relationship between text and image, Rothenstein was never really interested in simply retelling a story using visual means. Instead, his images speak to, but never exactly illustrate, the texts from which they draw. This strategy, which Pamela Fletcher has referred to as ‘anti-narrative’, was adopted by a few fin-de-siècle painters, including Rothenstein’s younger brother Albert, and their influential contemporary Walter Sickert.[5] It was also prevalent in the graphic arts, not just in the work of Beardsley (most famously in his ground-breaking illustrations for Wilde’s Salome), but that of William Strang also. Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, focussing on the graphic arts, has used the term ‘the artist as critic’ to describe this approach, in a deliberate attempt to address (even overturn) the seemingly subordinate role of illustration.[6]

This, I think, is where the most interesting correlations between the two artists exist. This is not to say, however, that there aren’t a few more concrete connections. Rothenstein, for instance, states in his memoirs that he believed Beardsley to have been directly influenced by his 1893 painting Souvenir of Scarborough (recently sold at auction) which shows a bonneted woman standing on Scarborough beach.[7] It was one of a series of paintings Rothenstein made depicting women adopting striking poses in dress suggestive of the 1830s. Another, slightly later, work at the Tate – Two Women, 1895 – continues the theme; as does the unfinished 1894 painting Woman Standing in a Doorway. Self-assured women in elaborate costumes: it’s not hard to imagine what may have attracted Beardsley. Souvenir of Scarborough, like the earlier painting Parting at Morning, would have made a good design for a poster.

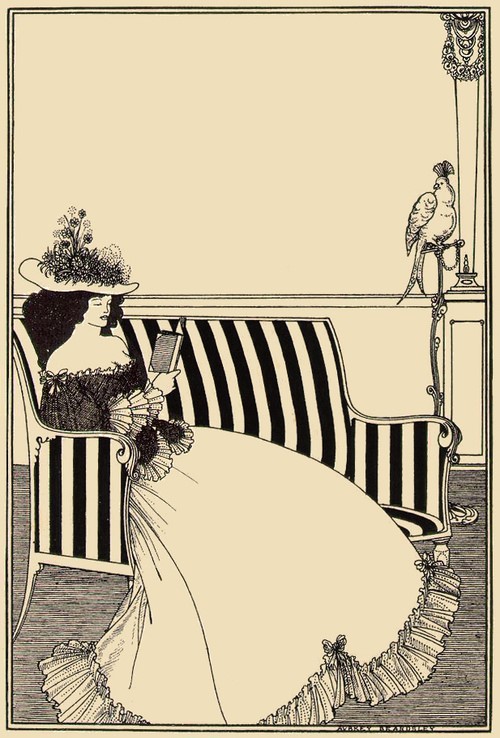

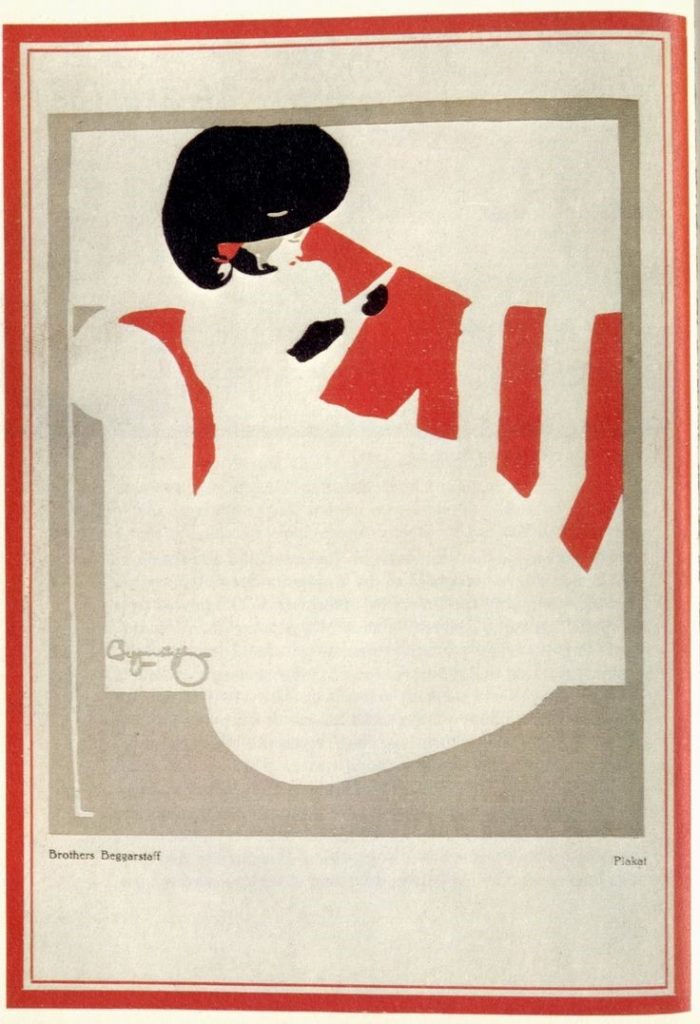

The most-discussed point of comparison between the two artists, however, revolves around Rothenstein’s 1894 painting Porphyria and Beardsley’s 1895 drawing Lady on a Sofa. Porphyria is a complex painting, taking its title from a poem by Robert Browning, while also including a sly portrait of the artist Charles Conder (reflected in a mirror on the right).[8] The woman sitting nervously on the sofa is the model Marion Gray, who had been recommended by Oscar Wilde. Linda Gertner Zatlin notes that Beardsley admired the painting greatly, and interprets Lady on a Sofa as a direct homage.[9] She also notes that James Pryde and William Nicholson (who collaborated as The Beggarstaff Brothers) produced a poster design in 1895 – Girl on a Sofa – that clearly takes picks up on Beardsley’s image, while reinstating the red-and-white stripes of Rothenstein’s original sofa. What is interesting here, among other things, is the movement of a common motif across different media: from a painting to an ink drawing to a poster design.

Rothenstein’s influence on Beardsley, and vice versa, certainly deserves further attention. Rothenstein himself stated that others – notably their mutual friend Robert Ross – were aware of it at the time, but that others (in this case Leonard Smithers, who was not on good terms with Rothenstein) sought to obscure it.[10] This may be true. What is equally evident is that Rothenstein – unlike some of his contemporaries – actively sought to distance himself from Beardsley and the 1890s in subsequent years. Although the Carfax Gallery, co-founded by Rothenstein and John Fothergill in 1899, and later managed by Robert Ross, would continue to exhibit Beardsley’s work into the 1900s, Rothenstein himself was moving on. Hardly any of the work he produced in the 1900s, for instance, would form an instructive comparison with Beardsley’s work. While Max Beerbohm was happy to attach himself to the ‘Beardsley period’, Rothenstein – perhaps wisely – understood the danger of being too closely associated with a particular historical moment. His great painting of 1899, The Doll’s House, marked an end-point of sorts; thereafter his paintings were much more austere in tone and subject matter. Some would argue that his talent dried up; it makes more sense, I think, to see it as a judicious change of direction. That strange mixture of the macabre and the frivolous that typifies art of the ‘nineties, Rothenstein’s included, is almost entirely absent from his post-1900 oeuvre. As if to signal this, Rothenstein stopped signing works with ‘Will’ and graduated to the full ‘William’. When he took stock of his career in the 1930s, he looked back on Beardsley with fondness. However he maintained his distance from the ‘Beardsley period’, tempering his fondness with criticism: there was, he reflected, ‘something hard and insensitive in [Beardsley’s] line, and narrow and small in his design […] He, too, remarkable boy as he was, had something harsh, too sharply defined in his nature’.[11]

[1] See William Rothenstein, Men and Memories, Volume One (London 1931) p.134

[2] Another anecdote leads us to a similar conclusion. Beardsley apparently gifted his 1894 drawing A Study in Major Lines to Rothenstein, who was apparently so shocked by the subject matter that he attempted to return it. This story rings less true; though Rothenstein could be a little prudish, it seems unlikely that he would have been startled by a picture which is, by Beardsley’s standards, relatively tame.

[3] For the dialogue see Linda Gertner Zatlin, Aubrey Beardsley: A Catalogue Raisonné; Volume One, (London, 2016) p.213-4 and Rothenstein, Men and Memories, Volume One, p.185. For more on the shared interest in Balzac see Samuel Shaw, ‘British Artists and Balzac at the turn of the twentieth-century’, English Literature in Transition, 1880-1920, 56:4, 2013, pp 427-444.

[4] Rothenstein’s writing on Goya appeared first in The Saturday Review, and was published in book form in 1900.

[5] For more on ‘anti-narrative’ see Pamela Fletcher, ‘Narrating Modernity: The British Problem Picture, 1895-1914’ (Aldershot, 2003)

[6] Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, The artist as critic: bitextuality in fin-de-siècle illustrated books (Aldershot, 1995)

[7] Rothenstein, Men and Memories, Volume One, p.184

[8] For further discussion of this in relation to Rothenstein’s early career see Samuel Shaw, ‘Narrative and Anti-Narrative’, in Samuel Shaw (ed.), In Focus: The Doll’s House 1899–1900 by William Rothenstein, Tate Research Publication, 2016, https://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/in-focus/the-dolls-house-william-rothenstein/narrative-and-anti-narrative, accessed 7 July 2020

[9] Linda Gertner Zatlin, Aubrey Beardsley: A Catalogue Raisonné; Volume Two (London 2016) pp.178-179

[10] Rothenstein, Men and Memories, Volume One, p.184

[11] Rothenstein, Men and Memories, Volume One, p.135