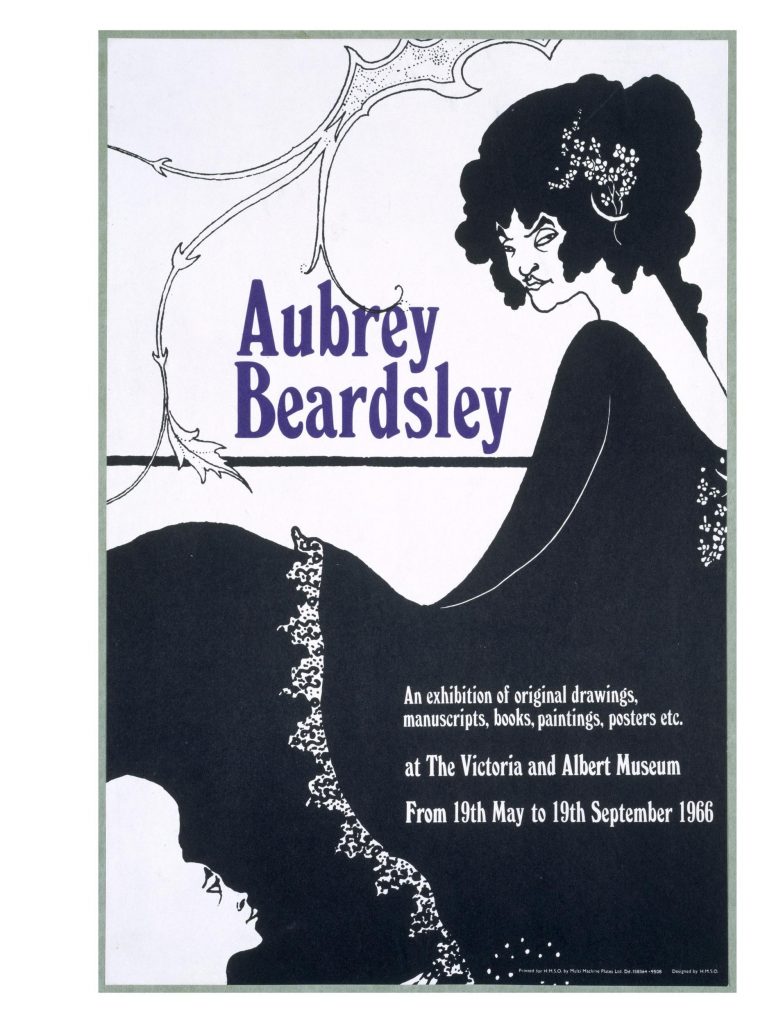

The image of Aubrey Beardsley has been long enveloped in an aura of notoriety with distinctly erotic overtones. He has been seen as a rebel figure in the era of militant philistine hypocrisy, his work, as ‘the artist’s gauntlet flung in the face of Victorian sexual mores’.[1] However, it is safe to say that wider Victorian society was blissfully unaware of Beardsley’s sexually explicit but clandestinely disseminated pieces. The myth of Beardsley as a Victorian sexual liberator was forged in what became known as the Swinging Sixties, owing to a major exhibition the V&A dedicated to the artist in 1966.

Curated by a great Beardsley scholar Brian Reade, the show opened the cult figure of the 1890s, hitherto well-known only among the connoisseurs, to a different and broader public, all the while exposing for the first time some of the more salacious aspects of his work. Today, as the largest exhibition of Beardsley’s art in fifty years has opened at Tate Britain, it is time for us to revisit the current show’s iconic predecessor, discussing exclusionary procedures, superimpositions of work and biography, and rules of narration which have governed the fashioning of Beardsley as the icon of notoriety.

The V&A display of 1966 included five rooms. The first one showed works influenced by the illustrator as well as various early fakes, evidence of the 1890s’ Beardsley Craze. The remaining four rooms concentrated on the artist himself and his oeuvre. The arrangement, as described by the catalogue, sought to maintain a chronological order. And yet, the show did thematise objects into a meaningful story that had an impact on successive generations of Beardsley’s scholars.

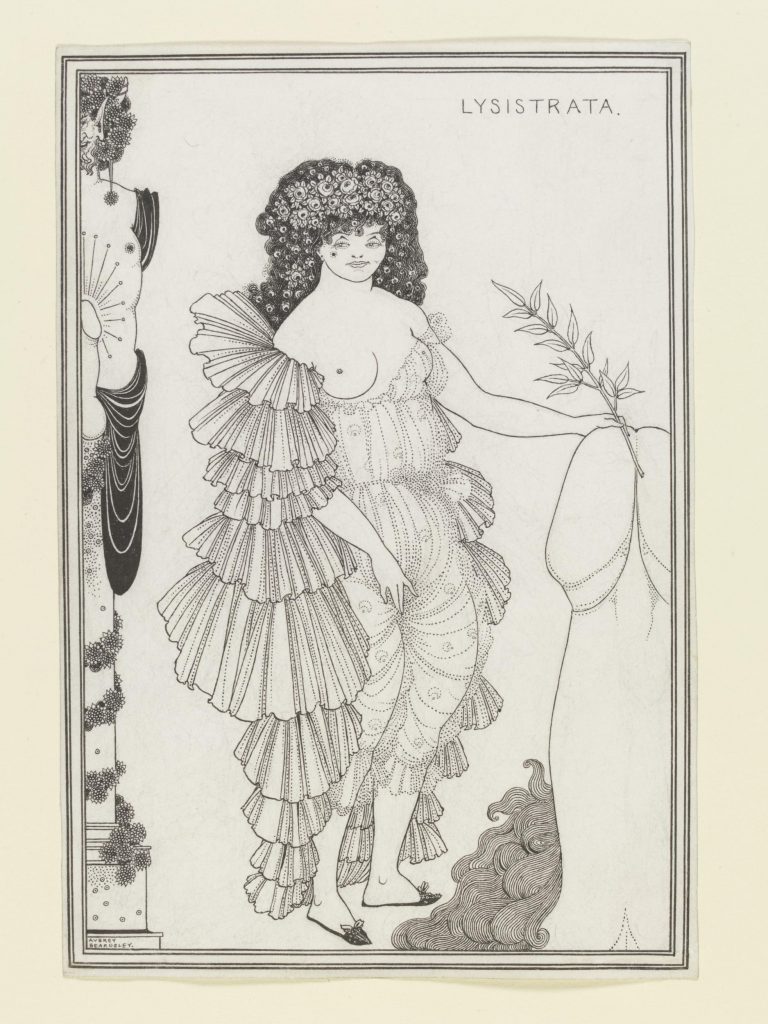

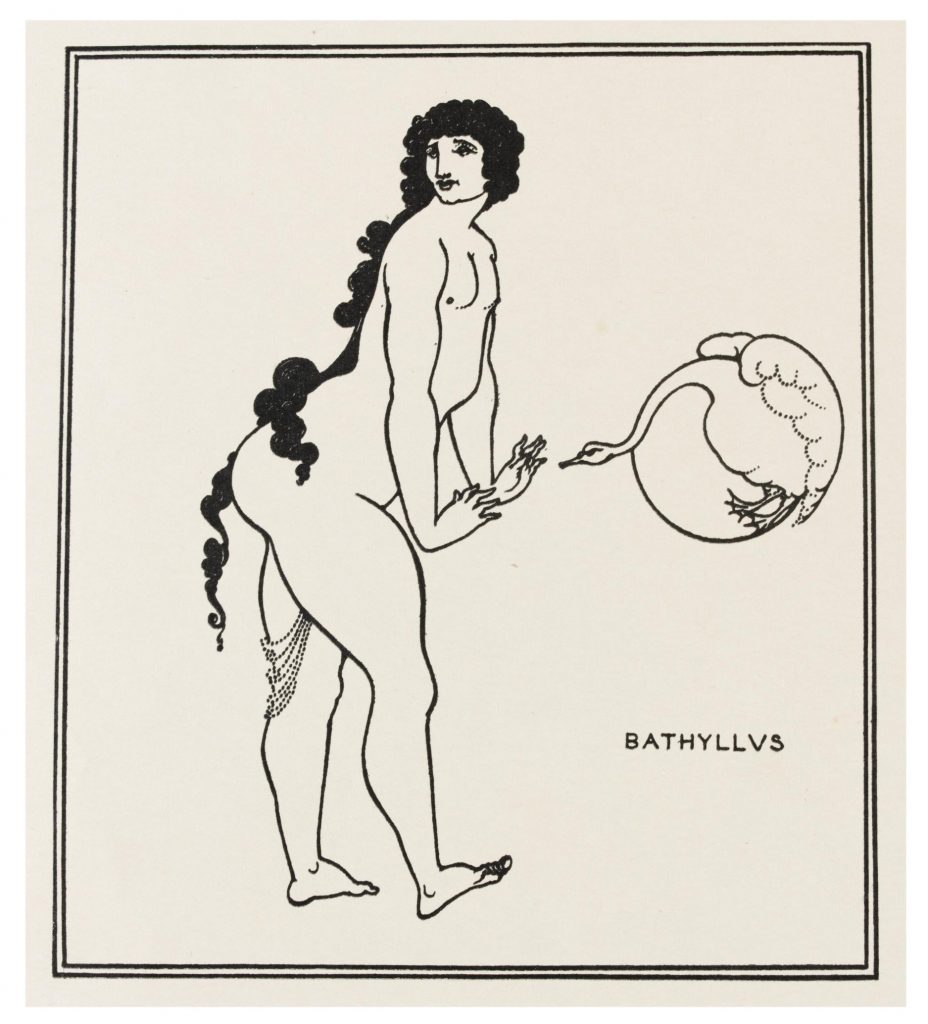

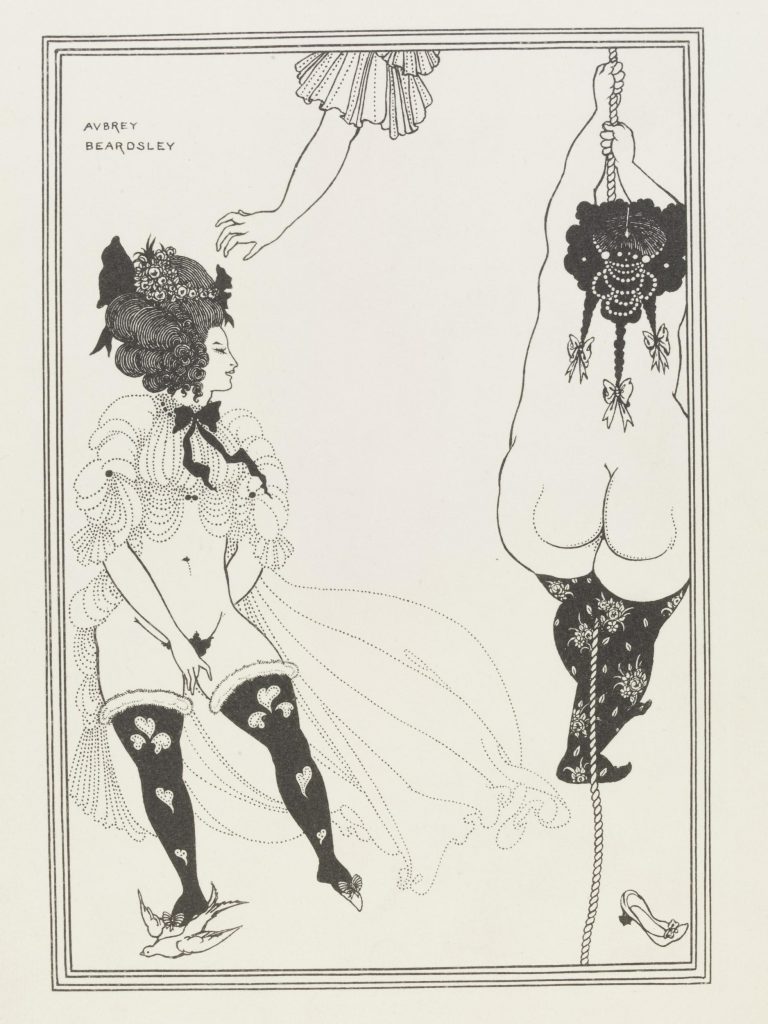

The tension culminated in the room which presented Beardsley’s now most famous designs for the Yellow Book (1894), the manuscript of his unfinished erotic novella Under the Hill (1896), audacious drawings for the Lysistrata of Aristophanes (1896) and the Sixth Satire of Juvenal (1895 and 1896). The Lysistrata set, with its parade of gargantuan erections mixed with scenes of female self-indulgence, had never been exhibited before. These bawdy illustrations were originally printed in an edition of 100 copies and distributed privately among the select clientele of Beardsley’s publisher Leonard Smithers. The homoerotic design Bathyllus in the Swan Dance for Juvenal likewise appeared before the public for the first time in 1966.

Significantly, the room also exhibited an original cablegram from the poet William Watson to the Yellow Book publisher John Lane which read, ‘Withdraw all beardsleys [sic] designs or I withdraw all my books’.[2] As we know all too well, the threat, inspired by Wilde’s arrest on charges of gross indecency, resulted in the removal of all Beardsley’s contributions from the fifth number of the periodical and his dismissal from the editorial office.

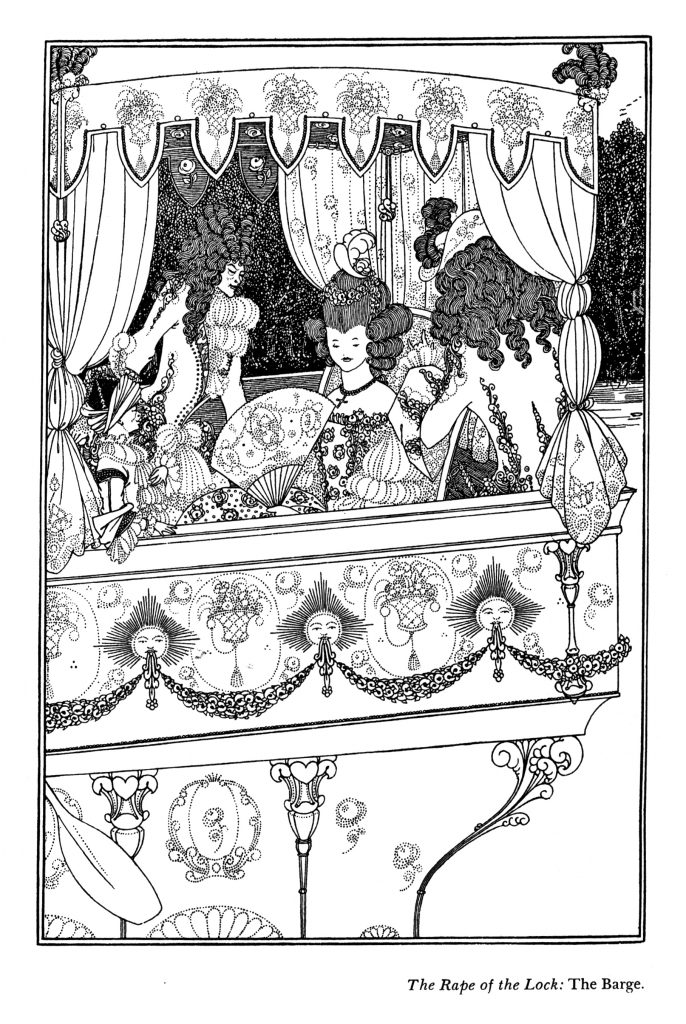

One might suggest that the room under discussion aimed at representing the dramatic peak of the artist’s ‘outwardly uneventful’ life.[3] Despite the curator’s claim for the chronological arrangement, Beardsley’s works that preceded Lysistrata and Juvenal with respect to the time of execution and publication, such as his innocent ‘embroideries’ for The Rape of the Lock, were put in the next room.[4]

Thus, the space within the V&A exhibition dedicated to Beardsley’s boom into notoriety presented a connection between his art-editorship of the scandalous Yellow Book, his expulsion in the wake of Wilde’s sexual scandal, and the production of his overtly sexual works. The viewers were invited, in other words, into the late-Victorian drama of sexual repression, transgression, and punishment. Such a representation reconciled available archive with relevant hagiographic qualities of Beardsley’s life. Reade’s emplotment of the artist has led to the construction of a queer visionary and martyr.

Although the three Lysistrata drawings that were chosen for the display – Lysistrata Haranguing the Athenian Women, Two Athenian Women in Distress, and Lysistrata Shielding her Coynte – are arguably among the tamest drawings of the set, the images did produce a sensation in 1966. Beardsley’s notorious status was affirmed when the police seized 200 ‘lewd’ prints from the shop ‘only two blocks away’ from the museum.[5] In December 1967, the Lysistrata designs were printed in Playboy, epitomising ‘Art Nouveau Erotica’, a product of ‘covert and perverse preoccupation with sex’ bred by ‘Victorianism’s overt prudery’.[6] Beardsley became a poster boy for the sexual revolution.

To learn more about the rediscovery of Beardsley in the 1960s, hear the keynote of AB 2020: Beardsley Re-Viewed Kate Hext’s talk, given at The Eve of St Aubrey: Re+Collecting Beardsley. The symposium took place on 16 March 2018 at Mary Ward House, marking 120 years since Beardsley died, in Oscar Wilde’s words, ‘at the age of a flower’ in Mentone. Today, on the 122nd anniversary of the artist’s passing, Beardsley’s admirers remain inspired by his art and its afterlives in the twentieth century and beyond.

[1] Linda Gertner Zatlin, Aubrey Beardsley and Victorian Sexual Politics (Oxford: Clarendon, 1990), p. 205.

[2] See the list of exhibits in Brian Reade and Frank Dickinson, Aubrey Beardsley Exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum: Catalogue of the Original Drawings, Letters, Manuscripts, Paintings (London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1966).

[3] Robert Ross, Aubrey Beardsley (London: The Bodley Head, 1909), p. 23.

[4] Beardsley reported in letters to Leonard Smithers and his sister Mabel that The Rape of the Lock was finished on 10 and 12 March 1896 correspondingly. The Lysistrata set was accomplished in July, and the work on Juvenal was not begun until August 1896. See The Letters of Aubrey Beardsley, ed. by Henry Maas, J.L. Duncan, and W.G. Good (London: Cassell, 1970), p. 118, p. 145, p. 150.

[5] ‘Beardsley Prints Seized in London. Shop Wares Called Lewd–Museum Showing Originals’, Times (New York), 11 August 1966, p. 25.

[6] ‘Art Nouveau Erotica’, Playboy, December 1967, pp. 129–137 (p. 129).